Funding for decarbonization is more accessible than companies think

New data show median climate transition funding equaled just 0.3 percent of revenues. Read More

- Consumer goods companies that account for ongoing greenhouse gas emissions at $15 to $20 per tonne can do so at a cost of less than 2 percent of revenues — and often much less.

- That “cost” in many cases consists of companies reinvesting into value chain improvements, signaling a preference for emissions reductions over market-based instruments.

- While companies are increasingly funding climate action in proportion to their carbon footprint, greater transparency and project-level data is essential to guide investment toward the most cost-effective solutions.

The opinions expressed here by Trellis expert contributors are their own, not those of Trellis.

Thanks to an increased push for transparency in corporate climate actions, customers and regulators alike have caught on to a chronic pattern of promises being made and forgotten. Key climate standard-setters stepped up in 2025 by pushing a shift from ambition to accountability. Notably, SBTI’s significant proposed revisions to the Corporate Net Zero Standard would improve progress reporting and even add a cost-per-tonne mechanism to create responsibility for ongoing emissions.

As we enter this new chapter, more companies will want to offer proof of follow-through in the form of empirical data showing that they’re adopting climate solutions. The subset of companies with an internal carbon price embrace the understanding that to put forth a credible climate strategy, details are key. In addition to showing whether companies are backing their targets with actions, details tell what companies are doing, and make it possible for learning to take place across companies.

This sort of data can be hard to capture and assess because approaches vary widely. But it’s possible. We recently analyzed the climate funding data of nearly 130 of the consumer brands that earned The Climate Label certification in 2025. The results show how they’re choosing to fund decarbonization, and preview the power that this type of data could have if collected at a larger scale.

Clearing the bar without breaking the bank

To earn The Climate Label, brands must make concrete investments in climate solutions, at a level proportionate to their carbon footprint. The level is based on a minimum internal carbon price of $15, which is applied to every tonne of their GHG emissions. The resulting dollar amount is known as a climate transition budget (CTB). Companies can only count verified decarbonization projects towards the CTB.

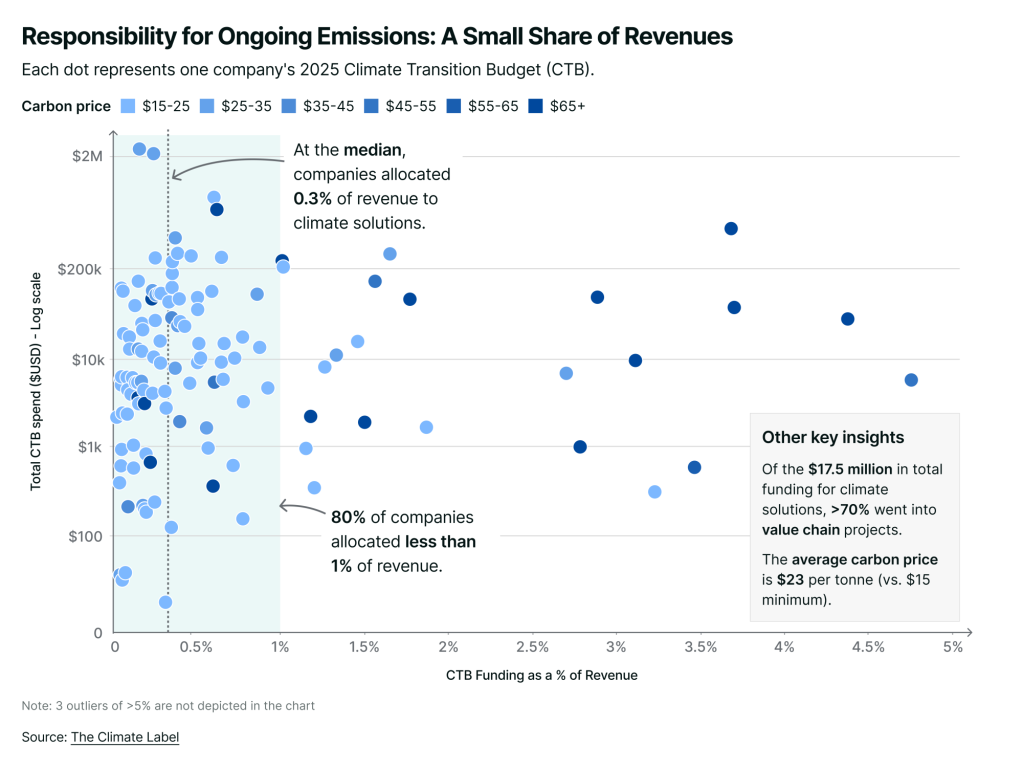

Last year, 96 percent of the 128 companies that earned the certification exceeded the minimum CTB of $15. Even counting companies that far exceeded the $15 per tonne level, median climate transition funding equaled just 0.3 percent of revenues, and 8 out of 10 brands met the CTB minimum for less than 1 percent of revenues.

While companies’ absolute emissions and total climate spend varied widely, CTB levels as a share of revenue showed little relationship to industry, company size or emissions profile. A meaningful level of funding for decarbonization may be more financially accessible than many companies assume.

Paying for value chain projects

A common criticism in corporate sustainability is that companies will usually opt for the easiest option—carbon credits—while continuing to make ambitious climate claims. The data, however, suggests the opposite.

Free to meet their CTBs with a mix of value chain projects and market-based mechanisms, certified companies directed an average of 70 percent of their funding into projects that involved corporate facilities and supply chains. This pattern held steady, regardless of sector or annual revenues, which ranged from a few million to hundreds of millions of dollars. Many companies noted they could better support their overall business strategy and long-term emissions reduction goals by making value chain investments.

Nonetheless, not all organizations have “shovel-ready” value chain projects at all times, particularly in the early stages of climate planning. As such, the flexibility to account for ongoing emissions by using market-based instruments, both within and beyond their value chains, remains important, and ensures that money continues to flow into climate solutions of some type.

An additional amount of funding in the 5 to 10 percent range on average went into efforts to build capacity for future value chain climate projects. Taken together, the allocations to direct mitigation efforts and capacity-building initiatives counter the notion that companies tend to rely too much on carbon credits, and instead point to a shift toward deeper, longer-term emissions reductions embedded within business operations.

Low carbon materials dominate value chain investment

As companies tackle their hard-to-abate Scope 3 emissions, they often seek to source low-carbon materials as a replacement for higher-carbon alternatives. This decarbonization lever received the greatest share of value chain funding. Adopting lower carbon materials is possible on a shorter timeline, compared to more complex operational or capital projects.

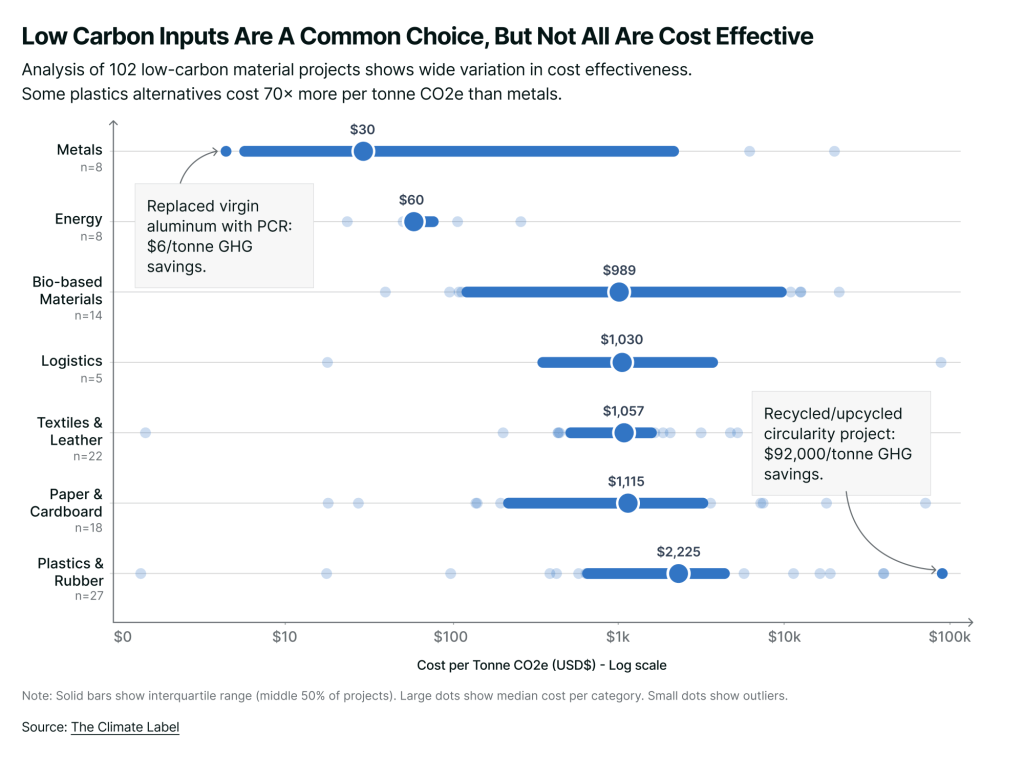

Despite a clear preference for low-carbon materials, it’s not clear that companies prioritize them based on their cost effectiveness. To document these initiatives, companies reported the estimated GHG savings of each initiative they invested in, along with price premiums. Costs per tonne ranged widely — from a few dollars per tonne to tens of thousands of dollars. Lower carbon metals and direct energy switching offered the most cost effective reductions, whereas lower carbon plastics and rubber offered the least cost effective reductions.

This exercise offered a side-by-side look at the costs of GHG abatement and helped companies understand how low carbon materials compare to other initiatives within their portfolio of decarbonization efforts. The insights can shape how these and other companies choose to allocate limited decarbonization budgets.

More project-level data is needed

Across the wider community of businesses actively involved in the climate transition, a majority aren’t well positioned to compare and identify projects with the lowest cost GHG abatement potential, because such comparative data doesn’t exist. Yet.

There is a significant opportunity to bring more climate transition funding data into the public domain by documenting it at the project level, across more companies and more projects.

Doing so would demystify many questions about cost effectiveness, and help sustainability professionals with their climate transition planning — leading to better outcomes from their climate initiatives.