GSK made the biggest climate promise in pharma. Can it keep it?

The company's path to its 2030 goals rests on dramatic reductions in two Scope 3 categories. Read More

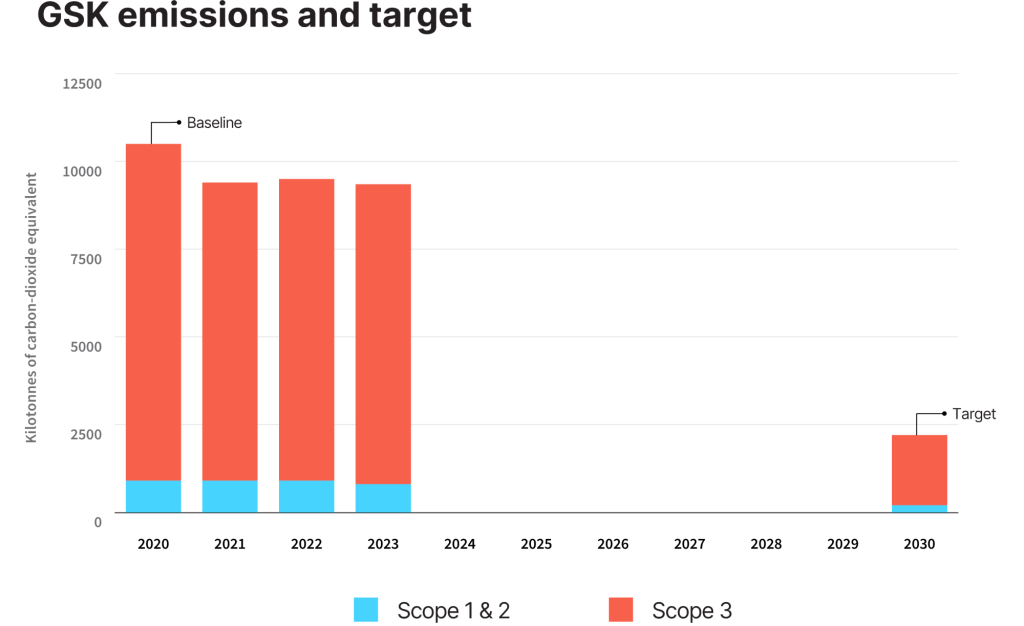

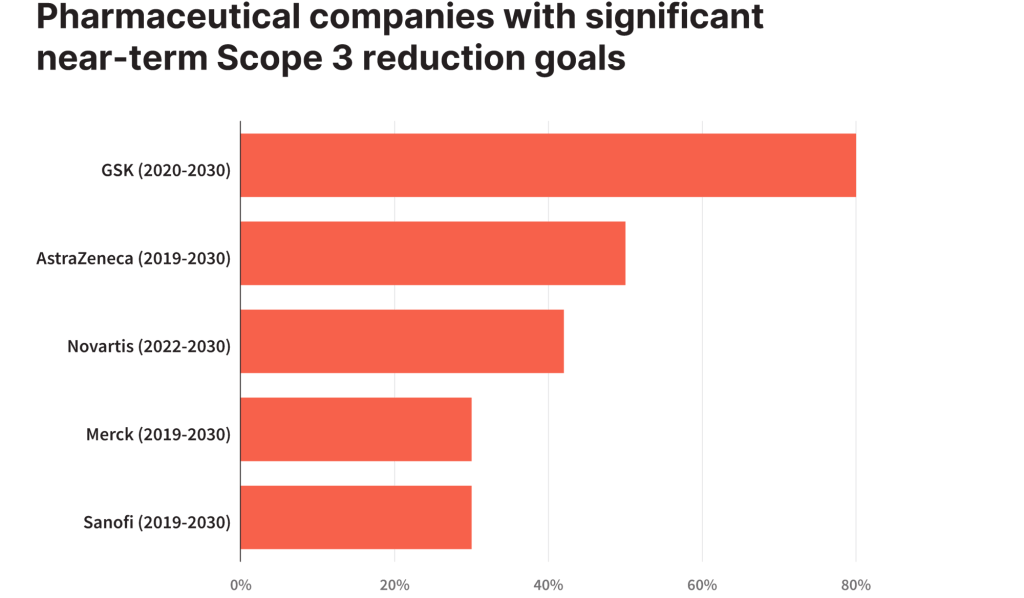

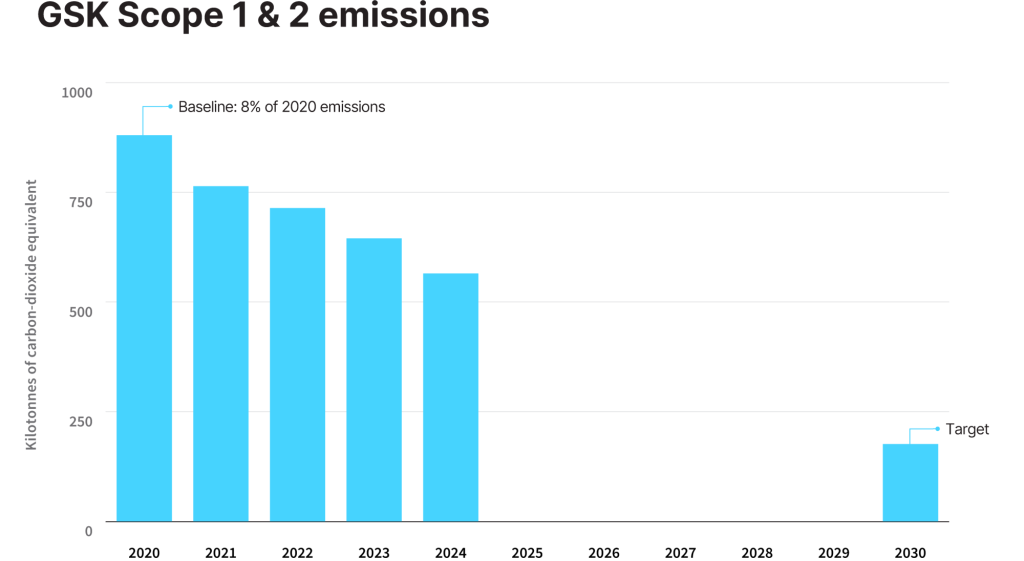

- By 2030, GSK has promised to slash emissions by 80 percent from 2020 levels, a far deeper cut than any of its rivals.

- It’s on track to hit this target for its own operations, mainly by shifting to renewable electricity for its plants.

- The British company is waiting for government approval for a low-emissions replacement for its asthma inhaler, which accounts for half of its overall emissions.

GSK has committed to reducing more emissions faster than any other large pharmaceutical company.

Now it has five years left to deliver.

Chasing Net Zero

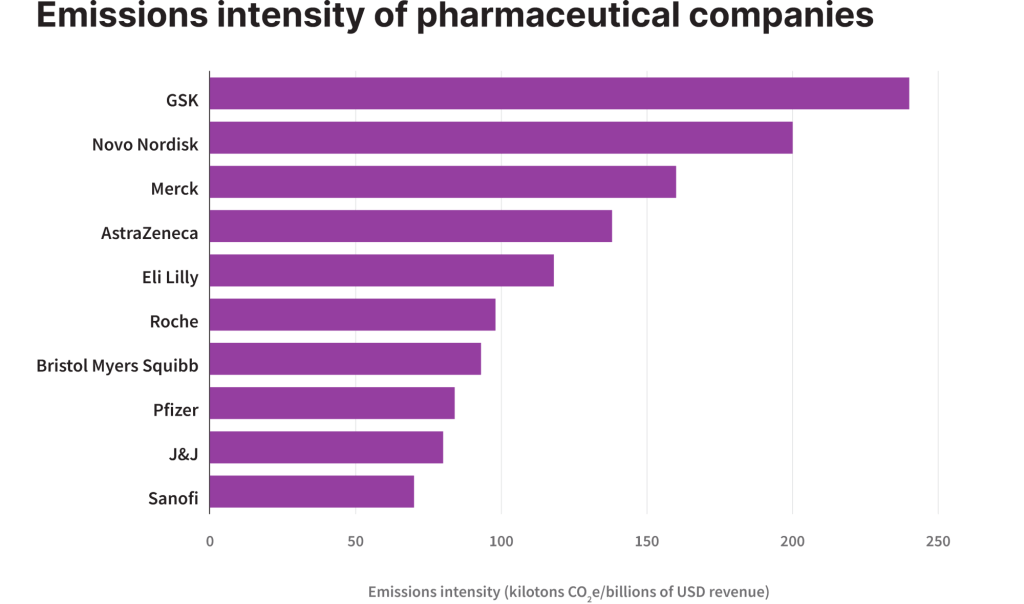

By 2030, the London-based pharmaceutical company has promised to slash direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent, relative to a 2020 baseline. It did so even though it has the industry’s highest emissions intensity, as measured by metric tons of emissions per dollar of revenue

So far, it is not on track to meet its goals. By 2023, the last year for which it published full data, GSK’s emissions had fallen 12 percent — half the pace it needs to reach its 2030 target.

But the numbers do not tell the whole story. This profile in the Chasing Net Zero series — our company-by-company look at progress toward 2030 climate goals that kicked off with Nestlé and IKEA’s biggest retailer — reveals that GSK’s decarbonization plan includes two initiatives that, if successful, would lead to dramatic emissions cuts.

One is common to almost all large companies: GSK is working with industry groups to convince pharma suppliers to reduce the emissions of their products. The news here is mixed: Ingredient manufacturers, many of which are in China and India, have started to engage, but actual emissions reductions have been slow to appear.

The other initiative is a sector-specific project that promises tantalizing results. If GSK can obtain regulatory approval and widespread adoption of a new version of its flagship Ventolin asthma inhaler, it would at a stroke eliminate close to half of its emissions.

GSK declined to make any executives available for this article, but in a recent podcast, Giulia Usai, GSK’s senior director for procurement sustainability, acknowledged the challenge of the 2030 deadline.

“We have less than 60 months to our target; that’s nothing,” she said. “It gives us all anxiety, but at the same time, it helps us prioritize the actions that will give us quicker results.”

The commitment: A big promise from a company in transition

Since taking over as chief executive in 2017, Emma Walmsley has faced relentless criticism from investors complaining that GSK lacks the lucrative pipeline needed to replace products losing patent protection. During Walmsley’s term, the company has fallen from seventh in the industry by revenue to 12th, in part because she spun out consumer businesses in 2022 to focus on lines with higher potential, including vaccines and treatments for respiratory diseases, HIV and cancer.

Despite these struggles, Walmsley has made unusually aggressive climate and nature commitments:

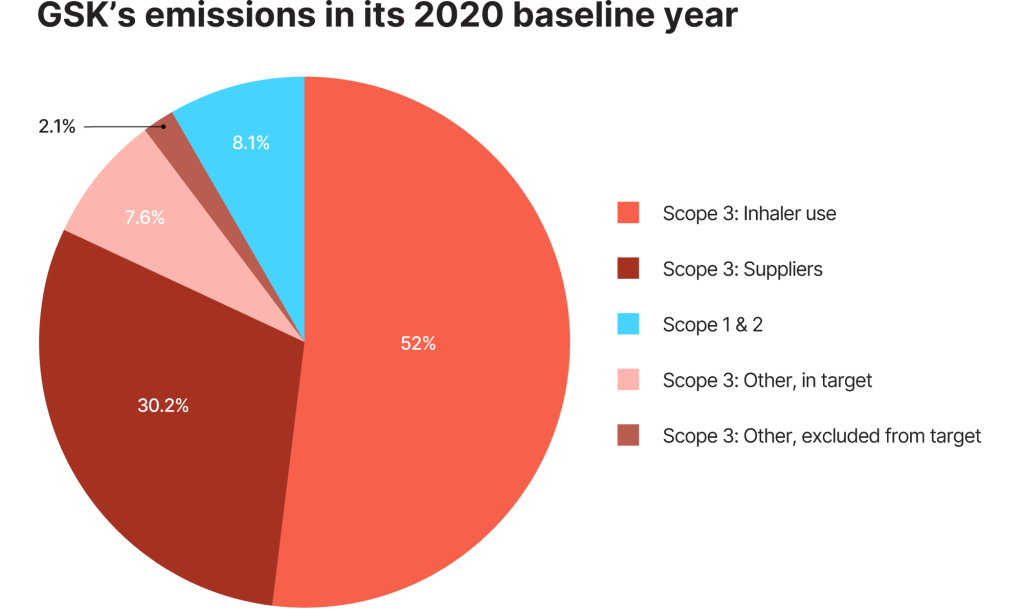

- Reducing GSK’s Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions — which totaled 11 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2020 — by 80 percent by 2030. (The company excluded Scope 3 categories representing 2 percent of its 2020 emissions from its goals.)

- Becoming carbon neutral by 2030 by using carbon credits to offset the remaining 20 percent of its emissions.

- Reducing its emissions by 90 percent from 2020 levels by 2045, a net-zero commitment validated by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi).

“They really understand the interconnections between health, climate and nature,” said Amy Booth, a University of Oxford researcher studying sustainability in the pharmaceutical industry. She praised GSK’s early commitment to transparency and to address its impact on biodiversity. (The company was the first to publish disclosures in line with Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures standards.)

“They are one of the better companies at reporting data,” she said. “They report extensively across Scopes 1, 2 and 3, and provide pages of methodology backing up their data.”

The context: Pharma companies are engaged

GSK is not alone in its industry in setting ambitious climate goals.

Eighteen of the top 20 publicly traded pharma companies have had near-term commitments validated by the SBTi. Several say they will eliminate nearly all of their Scope 1 and 2 emissions — those from company facilities and from purchased electricity, respectively — before 2030, largely by shifting to renewable electricity sources.

Eight of the top 20 also have long-term SBTi commitments. Seven are based in Europe, where drugmakers face pressure to reduce their climate impact from national health systems and European Union regulations that apply to all large companies.

More than 90 percent of most pharma companies’ emissions lie in value chains, with the largest component of these Scope 3 emissions coming from the raw ingredients in their products. Transportation can also be a significant source of emissions because many drugs require refrigeration, sometimes at very low temperatures.

Here GSK stands out: Its 80-percent Scope 3 commitment is the largest in the industry. The industry’s next highest Scope 3 goal is AstraZeneca’s, GSK’s larger British rival, which has promised a 50-percent reduction by 2030.

Scopes 1 and 2: Rapid shift to renewable energy

While Scopes 1 and 2 represent a small fraction of GSK’s overall carbon footprint, the company has made the largest reductions so far in this area, mainly by investing in renewable energy. It is increasingly purchasing electricity from renewable sources. And it’s replacing some of its on-site generators that burn fossil fuels with wind and solar generation systems.

Last year, for example, GSK activated two wind turbines and a 56-acre solar farm at its plant in Irvine, Scotland. The plant produces a majority of the world’s supply of the antibiotic Augmentin, which is made using an energy-intensive fermentation process. With the new capacity, more than half of the facility’s energy will come from its on-site wind and solar generation.

In addition, the company has made progress in improving the efficiency of its manufacturing processes, especially by reducing the gas leakage during inhaler manufacturing.

Scope 3: Reengineering a problematic product

GSK is the world’s leading maker of drugs to treat asthma and other respiratory diseases, propelled by the success of Ventolin, which it introduced in 1968. Even though GSK’s patents have expired and generics are available, 35 million patients worldwide used the company’s version in 2024, accounting for sales of almost $890 million, 2 percent of GSK’s revenue.

A puff from Ventolin’s ubiquitous L-shaped inhaler offers immediate relief from asthma symptoms. Unfortunately, each puff is also powered by R-134a, a gas that traps 1,400 times more heat than CO2. GSK plans to switch to a chemical known as HFA 152a, made by Orbia, the large Mexican company. The new propellant cuts carbon emissions by 90 percent.

It’s not as simple as substituting one gas for another, however. The drug formula and the inhaler mechanism need to be adjusted to work with the new propellant. The revised product is now in phase III clinical trials, and GSK hopes to submit the results for regulatory approval next year. HFA 152a is also highly flammable and has to be manufactured with elaborate safety precautions. GSK has started building new production lines for low-carbon Ventolin at its factory in Evreux, France.

“In the medicines sector, changing a product is costly, challenging and not guaranteed,” said Claire Lund, GSK’s vice president of environmental sustainability, on a recent podcast. “We have to work with multiple regulators in multiple countries, and we have to set up a global supply chain.”

Will GSK be able to accomplish the biggest item on its decarbonization checklist? While the results from the clinical trials are not yet available, there is evidence that the new class of propellants can be effective. Last month, British regulators approved a low-carbon version of AstraZenica’s Trixeo inhaler that used a similar propellant.

Scope 3: Coaxing suppliers

The prospects are harder to assess for GSK’s other major Scope 3 challenge: reducing the emissions embedded in the products it buys, especially the raw ingredients for drugs. These made up 30 percent of the company’s emissions in 2020. With just a 9-percent cut since 2020, progress is well short of the pace needed for an 80-percent reduction by 2030.

In 2021, GSK and six other drug companies formed Energize, an effort to help suppliers reduce their energy consumption. “It took a lot of blood, sweat and tears” to negotiate the legal agreements between rival companies, Usai said. Still, she concluded that “it’s going to be much more impactful to approach our suppliers as a group, as opposed to doing it on our own.”

Last September, for example, Energize negotiated a deal for five industry suppliers and three pharmaceutical companies to buy 560 GWh of renewable energy a year from seven new solar projects in Spain.

“Energize has gone above and beyond just telling suppliers to do stuff,” observes Booth, the Oxford researcher. “They are actually supporting them to get access to renewable energy.”

Another component of the goods and services challenge — getting suppliers to rethink how they manufacture products — has proven tougher than expected.

“However big and complicated you think the challenge is, it is probably even bigger and even more complicated,” the company wrote in a 2022 report on its climate efforts.

For example, GSK discovered the most significant emission sources for some suppliers were solvents, which are energy-intensive to produce and release volatile organic compounds that break down into greenhouse gases. GSK must now reach out to the makers of these solvents to encourage new, lower-emission production techniques.

“Green chemistry has a long time horizon,” observed David Linich, a sustainability partner at PwC. “Many pharmaceutical companies have started exploring green alternatives that have a lower environmental impact than traditional methods, but if you are starting the R&D now, you may not see the benefit for decades.”

It’s also not clear that all suppliers are eager to rework operations so that pharmaceutical companies can report lower Scope 3 emissions. After all, many of them are in countries such as China and India, where they are under less government pressure to cut emissions than they are in Europe. Growing international trade tensions may further discourage cooperation.

“You would think that Big Pharma has a lot of power to tell suppliers what to do, but it’s actually almost the opposite,” Booth said. “There may only be a niche supplier of an active pharmaceutical ingredient, and they can say we don’t need to sell to you because we have other customers.”

Big pharma companies also have massive, complex supply chains around the world, she said. “Their suppliers are often in countries that don’t have strict environmental regulations. And even if they want to take action, there may not be ready sources of renewable energy.”

Toward 2030: Getting numbers on the board

All this diligent effort doesn’t erase a cold fact: GSK promised to eliminate 8.5 million metric tons of emissions over the 10 years ending in 2030 and, during the first three years of that period, it shaved its emissions by just 1.2 million tons. (The company reported an additional cut of 0.5 million tons in 2024 from Scopes 1 and 2, plus some Scope 3 categories, but won’t release its full 2024 numbers until next year.)

If GSK can replace all of its Ventolin inhalers with its newer model, the company would wipe out another 4.1 million tons, leaving around 2.7 million remaining. To meet its target, GSK would need to reduce its supplier emissions and the other smaller Scope 3 categories by 50 percent.

There’s little in the results GSK has published so far or in the moves of its competitors to suggest that emissions reductions of this magnitude are possible over the next five years. A “Pathway to Net Zero” graph that GSK published earlier this year shows a slow reduction in emissions through 2026, followed by a drop so steep it would make a hardened roller coaster fan scream. The company declined to answer repeated requests to explain its thinking.

If GSK misses its target, it’s worth remembering the company set itself a bigger challenge than many of its peers. Companies that bet big on sustainability often get criticized for falling short. In this case, that may simply mean falling in line.

GSK, however, is not pleading for more time, at least not yet. In podcast interviews, GSK officials have suggested they initially put more emphasis on laying the groundwork for their reductions than finding savings that would appear in their published disclosures. As the deadline nears, they have a renewed focus on accomplishments they can boast about.

“We know that the projects like Energize are producing real savings,” Usai said. “Now is the time for us to show the benefits of what we’ve been doing to the world.”

Create your own user feedback survey

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders