20 years later, assessing the impact of a Walmart CEO’s ‘gutsy’ sustainability speech

Part triumph, part unfinished business. But no one disputes that Lee Scott's words changed the game. Read More

- Walmart’s sustainability journey has seen significant influence on competitors and supply chain sustainability.

- Despite progress in areas like renewable energy and waste reduction, its product sustainability goals remain the most challenging and least fulfilled.

- Scott’s speech was a transformative bet that catalyzed corporate sustainability efforts, but the unfinished work highlights the challenge of system-wide transformation.

This week, some 2,000 folks — businesspeople, NGO leaders, academics and others — are gathering in Bentonville, Arkansas, to mark the 20th anniversary of a seminal moment in the short history of sustainable business: a speech by the CEO of Walmart.

On Oct. 23, 2005, Lee Scott stood on the stage of the auditorium in Walmart’s Home Office to talk about “21st Century Leadership.” In a rare moment, the famously improvisational CEO held a script in his hands and read it word for word to ensure every sentiment was well articulated.

In the speech, Scott acknowledged the breadth of his company’s challenges, referencing “jobs, healthcare, community involvement, product sourcing, diversity, environmental impact: all the issues that we’ve been dealing with historically from a defensive posture.”

All of them, he said, “represent gateways for Walmart in becoming the most competitive and innovative company in the world.”

He reframed Walmart’s role, pledging ambitious sustainability leadership, and linked social and environmental stewardship with business efficiency while committing to workforce improvements.

Lasting influence

Scott committed the company to three ambitious environmental goals:

- Obtain 100 percent of the company’s energy from renewable sources

- Create zero waste

- Sell products that “sustain our resources and environment”

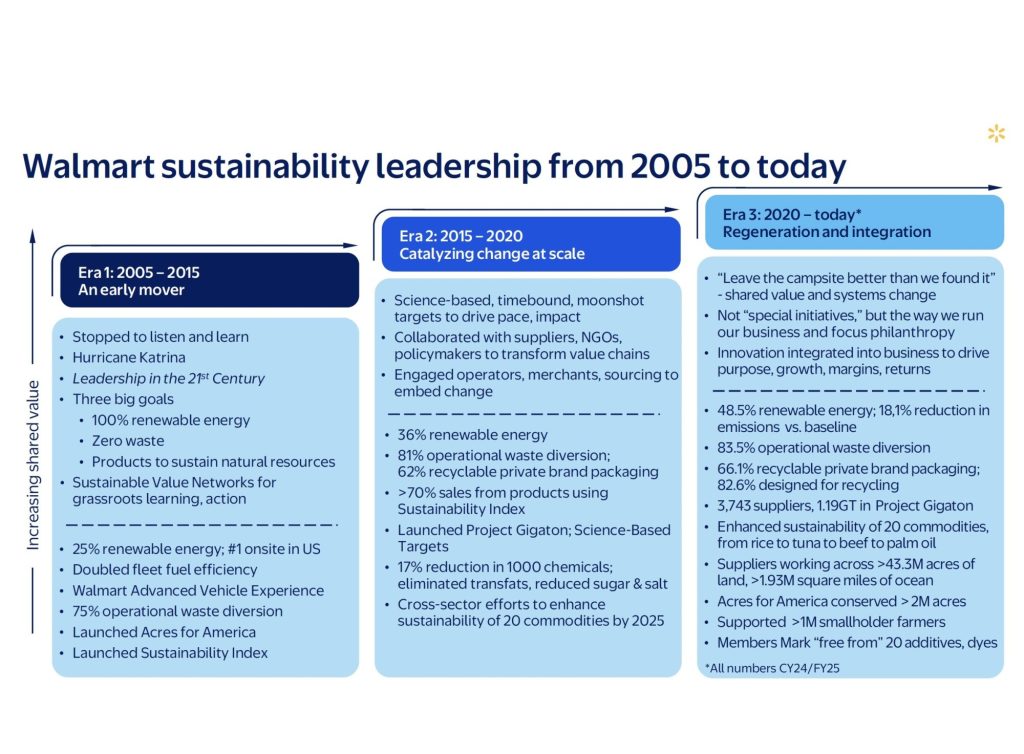

Walmart views its sustainability journey through three distinct eras. Source: Walmart

“These goals are both ambitious and aspirational, and I’m not sure how to achieve them, at least not yet,” Scott said. “This obviously will take some time.”

Those three goals set in motion myriad initiatives, partnerships and collaborations that have demonstrably moved the needle on Walmart’s footprint and have influenced other companies — suppliers, competitors and others — to follow along.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve spoken to nearly a dozen current and former Walmart employees as well as activists, academics and other observers. My quest: to assess the impact and influence of Scott’s speech, including its three sustainability commitments.

(For more backstory behind the speech, see this 2015 piece marking its 10-year anniversary.)

From pariah to partnerships

Until Scott’s speech, Walmart had little to do with sustainability. “We were doing our best to stop legislation that was warranted about runoff on parking lots from fertilizer,” Andy Ruben, who’d become Walmart’s first chief sustainability officer a year earlier, told me. “That’s what was going on in sustainability. It was a ticking time bomb of one more black eye the company could experience.” Everything else had been on the table, he said, such as the company’s impact on Main Street and on its labor force.

“But not this.”

Elizabeth Sturcken, vice president for net zero ambition and action at the Environmental Defense Fund, who has engaged with Walmart for nearly two decades, put it more bluntly: “They were a pariah.”

The year 2005 had already been a pivotal one for corporate sustainability. A few months earlier, for example, GE had launched Ecomagination. Other executives — Mark Tercek at Goldman Sachs, John Browne at British Petroleum, Jorma Ollila at Nokia, Chad Holliday at Dupont, Jim Rogers at Duke Energy and Bill Ford at Ford — were making headlines for their commitments.

For Scott, the time seemed right for a bold move.

‘A generous C’

So, how has the company fared? Scott’s three goals are still largely works in progress. Here are some stats, most culled from the company’s fiscal 2025 ESG Report:

- 48.5 percent of Walmart’s global electricity needs are supplied by renewable energy.

- 43.3 million acres of land has been “more sustainably managed, protected or restored.”

- Its Scope 1 and 2 emissions are 18.1 percent lower than the 2015 baseline.

- The company’s Scope 3 emissions have ratcheted up about 4 percent over the past two years, though its intensity — emissions per dollar of revenue — declined about 6 percent over that period.

- 83.5 percent of Walmart’s global operational waste has been diverted from landfills and incineration.

- 82.6 percent of its private brand plastic packaging is “designed for recycling.”

- 95.1 percent of Walmart U.S. fresh and frozen seafood, both wild-caught and farmed, was reported by suppliers as “more sustainably sourced.”

True, some of this language — “more sustainably,” for instance — is squishy at best. And transparency is sometimes lacking. For example, Project Gigaton, launched in 2017, blends reduced, avoided and sequestered emissions in its reporting and does not fully delineate each category with transparent, publicly verifiable breakdowns.

Still, these data points cover a two-decade period in which the company’s global revenue, adjusted for inflation, grew 44 percent, to $681 billion for fiscal 2025. That means that even as the company grew, several of its impacts didn’t.

Scott’s speech planted the seeds for a bumper crop of company initiatives. Some, such as its Sustainability Index (to establish a single source of data for evaluating the sustainability of products) and its Sustainable Value Networks (collaborations with suppliers, nonprofits and other stakeholders to improve product environmental performance) became part of the fabric, ran their course or morphed into other initiatives. Others, such as Project Gigaton, with the goal of removing a billion metric tons of greenhouse gases from Walmart’s supply chain, continue to be showcased by the company.

As graded by Jon Johnson, a professor in the Walton College of Business at the University of Arkansas, who’s been following the company for decades, “I would give them an A or A-minus on their waste and energy goals. I give them a C on their product goals, and that would be a generous C.”

Source: Walmart

Listening to critics

Assessing Walmart’s impact epitomizes the glass-half-full/half-empty challenge of sustainable business: Should a company be assessed on progress made or on work still to be done? That debate is particularly relevant to some of the world’s largest brands — McDonald’s, Amazon, Microsoft and others. For critics, it can be more rewarding to knock these companies’ failings — or fault the capitalist system within which they operate — than to acknowledge their achievements, however imperfect.

(This dilemma is highlighted in our Chasing Net Zero series, which examines companies’ progress, or lack thereof, in meeting emissions-reduction goals.)

In the case of Walmart, there’s been plenty to criticize: its low wages, which can cost taxpayers by increasing the need for public assistance programs among employees; an anti-union stance that chills worker organizing and protest; weak traceability of deforestation in its supply chain; packaging and waste goals that rely on voluntary supplier actions; chemical safety transparency gaps across its sprawling private-label and supplier networks. The list of perceived shortcomings goes on.

“We’re not a perfect company,” acknowledged Kathleen McLaughlin, Walmart’s current CSO. “One of the things that is pretty deep at Walmart, though, is really listening to everybody, to critics and to stakeholders.”

Ken Cook agrees. As president and co-founder of the Environmental Working Group (EWG), an advocacy group that focuses on environmental and public health issues, he has been engaging Walmart for much of the past two decades, with notable successes. For example, a 2014 EWG campaign led to Walmart requiring suppliers to limit or eliminate a set of “priority chemicals” in products it sells, particularly in household cleaning, personal care and beauty and cosmetic items. The company also agreed to recognize EWG Verified as part of its sustainability standards, meaning vetted products would be listed as complying with Walmart’s “Built for Better” criteria.

Cook noted that Walmart’s scale gave NGO standards such as his meaningful reach. “EWG is not interested in things that don’t make landscape-level changes,” he said. “This is what Walmart has provided.”

Another supportive group is EDF, which in 2007 opened an office in Bentonville adjacent to Walmart headquarters, the first NGO (and still one of the few) to do so.

Sturcken cited Walmart’s 2017 chemical footprint goal, aimed at restricting over 2,700 harmful chemicals in household products, as one example of the retailer’s influence. “You got very real ripple effects throughout the entire industry,” she said, citing Target and Dollar General as examples of retailers that followed suit.

“These past 20 years of work that Walmart has done on sustainability has transformed a generation of business,” Sturcken said. “They prioritized and democratized sustainability.”

Still, she added: “Walmart is not a sustainable company. They’re falling behind in their operational goals. And they’ve always had a big challenge and needed to do so much more on product sustainability and their supply chain.”

Mixed results on sustainable products

For Johnson, like for so many others, Scott’s speech “made the possibility that companies taking sustainability seriously could have substantial impact beyond government regulation,” he said. In 2009, Johnson co-founded The Sustainability Consortium, an ambitious effort to measure and standardize product impacts across consumer goods supply chains, launched in collaboration with Walmart.

That quest — the third of Walmart’s original goals, to sell more sustainable products — is arguably the most ambitious and the least fulfilled. Walmart has never adequately raised the subject in the buying rooms, where its buyers meet daily with suppliers’ representatives, Johnson said.

“Our task was to create a measurement reporting system for consumer goods,” he explained. He and his team at The Sustainability Consortium developed metrics that assess the impacts of products throughout their life cycle, “a good scientifically grounded system for understanding what those claims actually mean and whether they are meaningful,” as he put it.

“Walmart never used that information to make procurement decisions at any scale that had the effect we were hoping it would,” he added.

One issue may have been failing to prioritize the most environmentally problematic products. “We probably looked at every product as an opportunity to make it better,” Matt Kistler, Walmart’s second CSO, told me. “And there’s some products where the juice was not worth the squeeze. We should have been more focused.”

There were successes. In 2008, for example, Walmart phased out large bottles of laundry detergent, replacing them with compact versions that are now the industry standard, saving shelf space, labor, shipping emissions and costs. Compact fluorescent light bulbs were another bright spot. In late 2006, the company announced a goal to sell 100 million of them by the end of 2007 to save consumers money and reduce emissions, a goal achieved ahead of schedule.

But other products and packaging remain stubborn — plastics, in particular. Although Walmart has set ambitious targets, actual reduction in plastic packaging weight has been challenging, especially given business growth and the addition of packaging types, such as those used in e-commerce.

Can system transformation be scaled?

Taking the full measure of Walmart’s impacts turns out to be a complicated affair. For each shortcoming, there are unheralded successes.

For example, “We were late and slow on paying our people what they needed,” said Leslie Dach, who in 2013 stepped down from his role as Walmart’s executive vice president, where he oversaw sustainability, among other things. “I think we could have done more about people’s way of living.”

At the same time, he pointed out, “We followed a progressive agenda in sustainability, in women’s economic empowerment, in bringing manufacturing back from China,” including a 2013 initiative to reshore $50 billion worth of manufactured goods from that country.

Other initiatives have received relatively little media attention. One is the Gigaton PPA, which in part provides training and resources to help suppliers invest in renewable energy, including helping them reduce barriers to sourcing renewables. Walmart has worked with HSBC to launch a sustainable supply chain finance program to offer early payment to suppliers that set science-based targets or clear a CDP score threshold. Its Circular Connector, launched in 2022, aims to accelerate innovation in sustainable and circular packaging.

All of these and more, says CSO McLaughlin, are part of a bigger change the company is undergoing.

“The easier things have been tackled,” she said. “We’re now in the throes of true system transformation, and that’s hard work. At the heart of it, we’re talking about shifting the way that system functions so that it is elevating and regenerating people and the planet. That has to be the way that it works or it’s not sustainable.”

A regenerative Walmart? Stay tuned.

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders