Inside steel giant ArcelorMittal’s struggle to reach its 2030 climate goals

The largest steelmaker in the Global North is accused by critics of prioritizing returns to shareholders over decarbonization. Read More

-

-

Oversupply and high energy prices are holding back low-carbon investment across the steel industry.

- Luxembourg-based steel giant ArcelorMittal has largely failed to deliver on its 2021 decarbonization agenda.

- Arcelor and some peers have prioritized returns to investors ahead of longer-term decarbonization investments.

-

The story of sustainability at the steelmaking giant ArcelorMittal reads like a years-long courtroom drama.

Chasing Net Zero

Environmental groups have led the prosecution. ArcelorMittal generated just over 100 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2024, roughly on par with industrialized nations such as Belgium or Chile. Emissions of that size demand urgent attention, argue the company’s critics. Instead, ArcelorMittal has failed to build the green steel plants promised in its decarbonization agenda, while simultaneously returning billions of dollars to shareholders and building high-emissions facilities in India.

The defense from the company has been steadfast, and often backed by industry insiders. In this view, ArcelorMittal is committed to decarbonization but constrained by the steel market, which is being roiled by over-supply, high energy prices and a lack of government support for low-carbon initiatives. The company would like to decarbonize faster, it and other steelmakers insist, but economic realities make that impossible.

In this installment of Chasing Net Zero, our company-by-company look at progress toward 2030 climate goals, Trellis assesses the dueling narratives surrounding the largest steelmaker headquartered in the Global North. The disputes turn out to have little to do with decarbonization technologies or emissions data. The two sides broadly agree on the challenges the industry, which is responsible for around 8 percent of global emissions, faces in reaching net zero. Beneath the rhetoric, what’s in dispute is something more fundamental: which stakeholders a company should serve and, in the midst of a climate crisis, what constitutes leadership?

ArcelorMittal’s climate commitments

ArcelorMittal’s 2021 Climate Action Report, the origin of most of its current goals, was a feast of commitments:

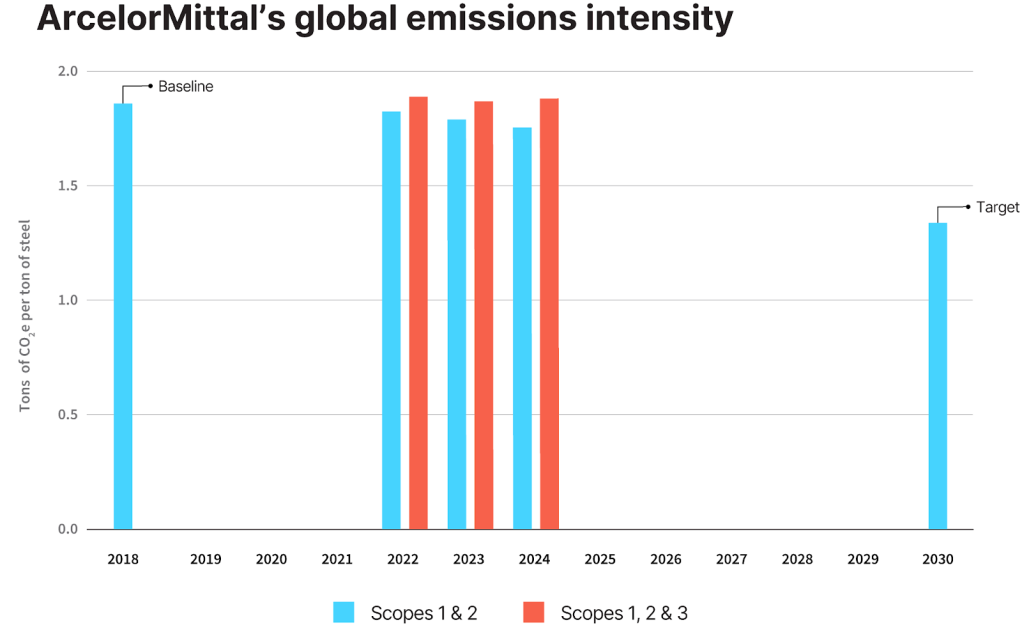

- Global emissions intensity, defined as the carbon released for every ton of steel produced, would fall 25 percent from a 2018 baseline by 2030.

- A more ambitous 35 percent drop for European operations.

- Reaffirmation of an earlier promise to reach net zero by 2050.

- A two-year timeline for validation of its targets by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi).

The journey to these goals was also mapped out, including plans for more recycled steel and transitioning to clean energy sources. The flagship project would be what ArcelorMittal billed as “the world’s first full-scale zero carbon-emissions plant,” slated to come online in Sestao, Spain, in 2025.

The total cost: $10 billion by 2030, around a third of which the company said it would deploy by 2025. No small sum, but Arcelor, headquartered in Luxembourg, had the clout to follow through. It’s the world’s second-largest producer of steel, according to the World Steel Association. It makes steel in 15 countries, employs 125,000 people and generated $62 billion in revenue in 2024.

Four years later, the future envisioned in 2021 is barely closer to reality. ArcelorMittal’s absolute emissions have fallen by close to half, but almost all of that drop is due to declining production and asset sales. A better gauge of the company’s net-zero transition is emissions intensity, which has dropped by just 5.4 percent globally and 5.0 percent in Europe — well short of the pace required to hit its 2030 targets, which the company said in a November 2024 update that it was “increasingly unlikely” to meet.

What’s more, ArcelorMittal’s target only covers direct emissions from its steel plants and the electricity they consume — Scopes 1 and 2, in other words. This omits other significant sources, including upstream Scope 3 emissions from mining. When those emissions are added, progress all but evaporates.

As for plans to work with the SBTi, these also dissolved; the company’s commitment to set a near-term target with the organization was removed last year after the deadline for doing so expired.

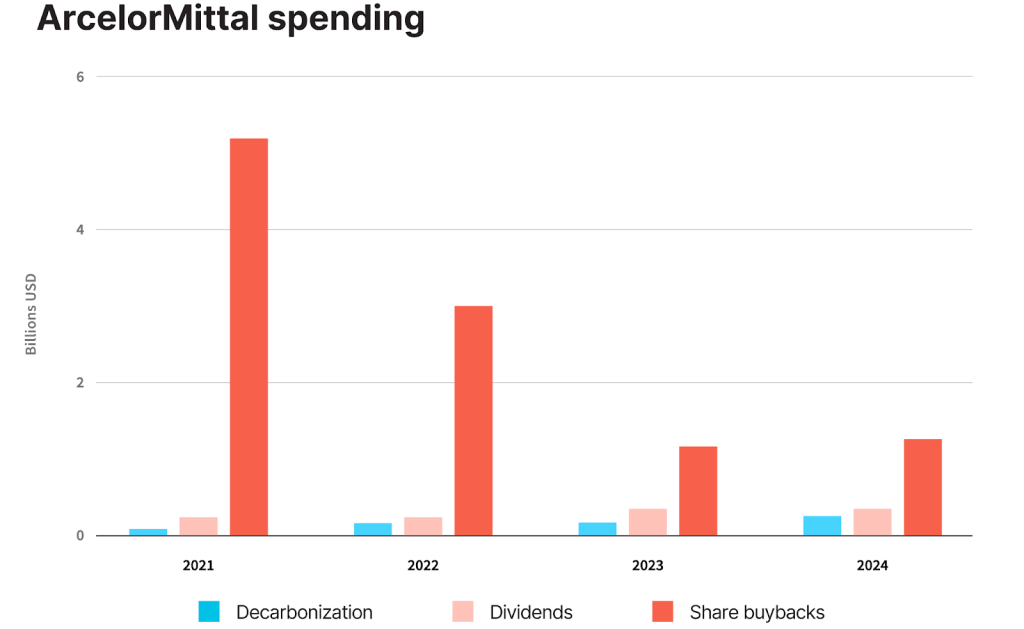

In Spain, a critical part of the Sestao project is on hold. So are several other low-carbon projects in Europe, which was to be the focus of the company’s decarbonization push. ArcelorMittal’s total decarbonization spending between 2021 and 2024 was $1 billion — again, far behind the pace envisioned in the company’s climate action plan.

What’s more, the company’s calculations omit emissions from a 2019 joint venture with Nippon Steel in India, known as AM/NS. The company, of which Arcelor holds 60 percent, relies on conventional, high-emissions facilities. AM/NS emissions in 2024 were 17 million tons, placing Arcelor’s share at 10 million tons. That would increase ArcelorMittal’s total emissions by almost 10 percent, were the company to include them in its global total. But while revenue from the joint venture is included in the company’s financial statements, the emissions are omitted from its sustainability report.

The industry is off track

From a planetary perspective, ArcelorMittal’s net-zero narrative makes for depressing reading. From an industry point of view, it’s pretty much par for the course.

“We’re not an anomaly,” said Nicola Davidson, Arcelor’s vice president for sustainable development and corporate communications.

Things looked different when the company set its targets in 2021. ArcelorMittal planned to reduce emissions by transitioning existing steel production, which relies on a form of coal known as coke, to newer technology powered by clean hydrogen. Since clean hydrogen remains expensive, natural gas could be used as an interim step. The company also planned on using more scrap steel as an input, which further reduces emissions relative to freshly mined iron ore. To make the economics pencil out, Arcelor said its own investments would need to be accompanied by billions of dollars in government support, together with buyer commitments to pay a premium for low-carbon steel.

Then geopolitics intervened. Natural gas prices in Europe soared after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which happened around six months after Arcelor’s plan was released. Margins have been further hit by cheap exports from China, which manufactures around half the world’s steel and has significant excess capacity following a slump in domestic demand. Government support can buffer these forces; Arcelor has been offered around $3.5 billion in subsidies to build green steel facilities in Europe. But the company insists this is not enough, and that it is forced to delay because decarbonization is uneconomic under current conditions.

Another factor is limited demand for green steel, which Davidson says Arcelor can “comfortably” meet with its existing lower-carbon facilities. “Everyone will say they want low-carbon steel,” she said, “but will they actually pay for it? No. And the reality is that it does cost more, and steel is a very low-margin industry.”

Arcelor adds that while progress might not have been as rapid as critics would like, it’s not standing still. Where it’s economic to do so, the company says, it is transitioning away from fossil-fuel powered furnaces to less emissions-intensive electric arc furnaces: In 2024, the latter produced 25 percent of ArcelorMittal’s global output, up from 19 percent in 2018. It’s also processing iron ore using natural gas where it can, rather than using coke.

These initiatives haven’t fundamentally changed Arcelor’s contribution to climate change. But Arcelor is not alone in making slow progress. To hit net zero by 2050, the industry needs to have built around 90 near-zero emissions plants by 2030, according to the Mission Possible Partnership, which brings together companies from emissions-intensive industries. By April of this year, the partnership counted three such facilities in operation, with only nine more having reached a final investment decision.

As a consequence, emissions intensities remain high relative to net-zero goals. To decarbonize in line with 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming, average intensities should have fallen to 1.46 tCO2e per ton of steel in 2022, the most recent year for which the Transition Pathway Initiative, a research project, has data. The actual figure was 10 percent higher — and had grown over the previous year.

There are bright spots amid this gloomy picture, but they are exceptions. Four companies have had near-term and net-zero targets validated by the SBTi, for example, including the Swedish steelmaker SSAB. Sweden is also home to Stegra, a groundbreaking facility that will use clean hydrogen and electricity to produce clean steel when it enters service next year. Don’t expect a flood of similar projects, however: Sweden is unusual in having plentiful clean energy — 99 percent comes from low-carbon sources — available at prices that are among the lowest in Europe, together with easy access to iron ore.

On the other end of the spectrum sits India. The country lacks natural gas, a potentially useful interim decarbonization measure, as well as scrap steel for recycling, buyers willing to pay a premium for green steel and a government willing to fund substantive decarbonization in the industry. Thus ArcelorMittal faces a choice: Grab a share of the burgeoning Indian market using conventional high-emissions technology, the only economically viable method at scale, or stay out. And India is one of the few countries where the industry sees potential for significant growth.

“If you’re ArcelorMittal, you’re looking at your portfolio and saying, ‘Where do I grow? Where can I be on the offense rather than defense?’ It’s India,” said John Lichtenstein, a managing partner at World Steel Dynamics, a U.S.-based consultancy and analytics firm.

Arcelor’s choices

At the heart of ArcelorMittal’s net-zero journey lies a question about who a company should serve.

For many investors, the answer is simple: shareholders. Companies will rarely advocate for such a narrow framing, or at least not in public. Most feel compelled to subscribe to a broader conception of corporate purpose — think: “stakeholder capitalism” — that encompasses people and planet alongside profit.

One key test of a company’s position is how it allocates capital. It’s here that ArcelorMittal’s claims about economic challenges have attracted particular scrutiny. In 2021, the year it launched its climate action plan, and the following three years, the non-profit SteelWatch estimates that Arcelor returned around $12 billion to shareholders, mainly by buying back its own shares. That dwarfs the $1 billion the company spent on decarbonization.

Arcelor framed this as returning free cash to investors — a defensible stance when decarbonization projects face so many headwinds. The view is bolstered by signs that steelmakers with more ambitious decarbonization plans are encountering obstacles. Germany’s Thyssenkrupp Steel, for example, is another with an SBTi-approved target; it recently announced plans to cut or outsource 11,000 positions from its 27,000-strong workforce.

“At the end of the day, shareholders, stakeholders, they don’t expect companies and company leaderships to destroy value,” said Davidson. “They expect you to create that.”

“In this environment, the prospect of generous investment in new productive assets may seem irresponsible,” noted Isha Chaudhary, a research director at Wood Mackenzie, a data and analytics provider. “Instead, the priority may be to continue business and eke out a profit margin as far as possible.”

The market seems to broadly agree. ArcelorMittal’s stock is up more than 150 percent over the past half-decade, comfortably outperforming the S&P 500 and in the middle of the pack relative to prices changes at other large global steelmakers, such as Nippon Steel, South Korea’s POSCO and India’s Tata Steel.

If you take a broader view of corporate responsibility, however, the twelvefold difference between funds returned to shareholders and decarbonization spending is a failure of leadership that exposes the company’s claim that it cannot invest more in clean-steel projects. “We believe they have the capital to do it,” said one steel industry analyst, who asked not to be named because they have a direct relationship with Arcelor.

Arcelor insists that it would not make economic sense to do more, but industry experts who spoke to Trellis cited opportunities. The company could build smaller hydrogen-powered steelmaking facilities than it initially planned. Or do more to transfer lower-emissions processes from Europe and the U.S. to less wealthy nations. “They could be the model of Global North bringing green technologies to Global South,” said Caitlin Swalec, director of the heavy industry program at Global Energy Monitor, a nonprofit data provider.

“What steelmakers do is start with the question of what’s feasible given today’s bottom line and today’s technology constraints,” said Caroline Ashley, SteelWatch’s executive director. “In a world where climate change is accelerating around us, we don’t actually think that’s the right question. The question should be: ‘What is essential to make our contribution to addressing climate change and where do we have to take new risks?’”

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders