How Intel’s sales tailspin sidelined its 2030 sustainability ambitions

The company that commercialized the microprocessor also took an early lead on sustainability. Now, after a decade of business turmoil, it’s quietly scaling back its climate efforts. Read More

- A critical technology mistake undermined Intel’s business and stalled progress on sustainability.

- The company’s new CEO has pushed back a key climate commitment and dropped others.

- Competitors in South Asia report poorer sustainability scores, but are closing the gap.

For many years, Intel was an American success story: the most valuable chipmaker in the world and the undisputed leader in the manufacture of microprocessors, the brains inside personal computers and internet servers.

Its sustainability ambitions led the industry, as well.

Chasing Net Zero

For nearly a decade, Intel bought more clean power than any other U.S. company. It was also an early leader in tackling the powerful greenhouse gasses released in the chipmaking process and known for setting ambitious emissions targets. As a percent of revenue, the company’s emissions peaked in 2006 and remain far below other major manufacturers.

Then Intel’s business faltered, and so did its climate action.

Over the past 15 years, the semiconductor behemoth has foundered as rivals captured new markets for chips used in smartphones and artificial intelligence data centers. A strategic misstep left its chips a generation behind the state of the art. Intel’s sales and share price plummeted, forcing it to lay off a quarter of its workforce this year.

This profile — the latest installment in Chasing Net Zero, our company-by-company series that has probed the climate strategies of Nestlé, Salesforce and others — reveals how business storms have eroded Intel’s once-lauded climate strategy. A critical near-term supply-chain goal was quietly dropped under its new CEO, for instance, and the company no longer ties executive compensation to emissions.

Intel declined to make executives available for this article, but said in a statement that it is “committed to achieving a more sustainable future by advancing bold, measurable goals.” Analysts, however, say its progress towards those commitments has slowed as it fights for survival.

“I wouldn’t say that Intel has stopped caring about sustainability, but they have more pressing concerns right now,” said Stephen Russell, a senior technical fellow for sustainability at Techinsights, an Ottawa semiconductor consulting firm. “They’ve fallen behind — and they are desperately trying to catch up.”

When Intel led on climate

Intel’s climate efforts began in the late 1990s when, under pressure from the Environmental Protection Agency, the company joined an industry group to scale back its emissions of fluorinated gases. These “F-gases,” used to carve microscopic circuits onto the surface of silicon wafers, have thousands of times the warming power of carbon dioxide when leaked into the atmosphere.

In the following decade, the company also turned its attention to the electricity consumed by the machinery used to squeeze millions of transistors onto chips the size of postage stamps. Using renewable energy certificates (RECs), which allow companies to claim credit for using green energy by funneling money to renewables projects, Intel became the nation’s largest buyer of clean power between 2008 and 2016, according to the EPA.

These initiatives helped Intel’s operational emissions — Scope 1 (mainly F-gases) and Scope 2 (the electricity it buys) — peak at 4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2006. By 2019, emissions had declined to 2.8 million tons, even as the company’s revenue doubled. That same year, it stepped up its ambition with goals to use 100 percent renewables and shave 10 percent more off operational emissions by 2030.

As with most companies, however, these sources are dwarfed by emissions from Intel’s value chain.

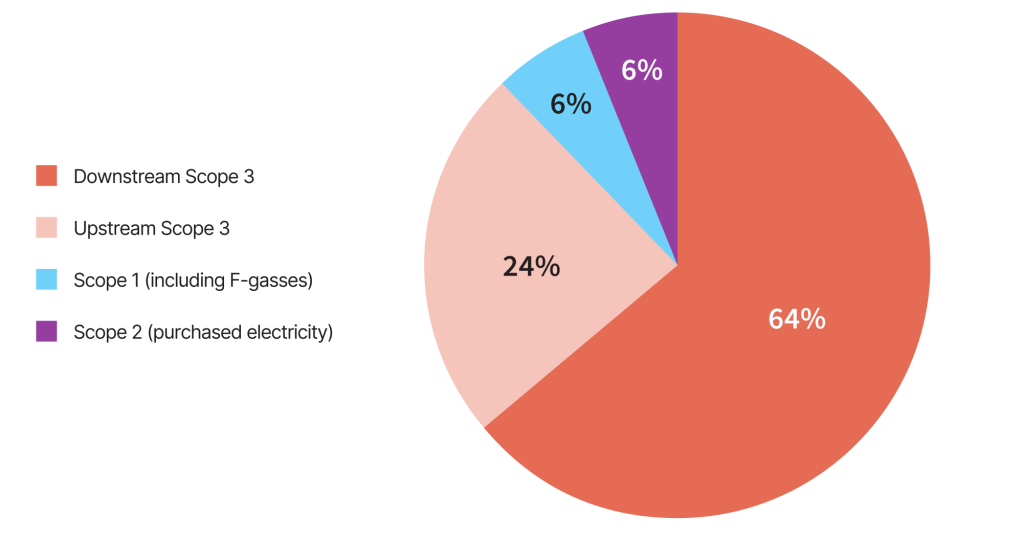

Intel’s emissions in its 2019 baseline year

In 2019, the electricity used to operate chips sold by Intel (downstream Scope 3) accounted for two-thirds of the company’s footprint.

Chipmakers tackle these emissions by designing less power-hungry chips — Intel’s target is a tenfold efficiency improvement by 2030. But making chips more efficient encourages greater use, which drives up emissions. The trend is compounded by demand for chips to power AI applications. And the ultimate solution to Intel’s downstream Scope 3 emissions is the decarbonization of global grids — not something within the company’s control.

One area of Scope 3 where the company has more influence is emissions generated by its suppliers, which represent a quarter of Intel’s footprint. In a target announced in 2022, the company said it would reduce supplier emissions by 30 percent by 2030 “from what they would be in the absence of action.”

The upgraded near-term commitments were capped off with a long-term goal to reduce Scope 1 and 2 emissions to zero in 2040. A few years later, after activist shareholders asked for more, Intel published a detailed climate transition action plan and committed to a net-zero upstream supply chain by 2050.

These are meaningful goals, particularly as the semiconductor industry has become a major contributor to climate change. Each new generation of chips requires more electricity and F-gases to manufacture, and by 2030 chipmaking is expected to account for 0.5 percent of global emissions.

These goals compare favorably to Intel’s two main competitors in processor manufacturing, fast-growing Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and the semiconductor division of consumer electronics giant Samsung. Both target net-zero value chains by 2050, a decade later than Intel’s operational emissions goal. Samsung lacks a near-term target, and TSMC only added one this year: a commitment to return its Scope 1 and 2 emissions to 2020 levels by 2030.

Most other semiconductor companies, such as Nvidia, the high-flying AI chip maker, are “fabless,” meaning they outsource manufacturing and can claim relatively low Scope 1 and 2 emissions as a result.

How Intel stalled on emissions

With operational emissions falling and its commitments gaining in ambition, the Intel of five years ago had one of the most ambitious climate programs in the semiconductor industry. But the company was also grappling with the consequences of a bad bet made the previous decade.

As they considered how to etch ever-smaller circuits onto the next generation of chips, Intel’s engineers had deemed one new technology — using extreme ultraviolet light to draw finer lines on silicon — too difficult to work with. They opted instead to adapt existing methods, an approach that proved even more challenging to implement. Intel’s next-gen chips, due in 2015, were delayed for years. Meanwhile, TSMC successfully brought its next-gen chip to market using ultraviolet technology.

Intel’s delay meant it didn’t build new fabs with the latest approaches to capturing F-gases as rapidly as its rivals. Eventually, Intel bought its own ultraviolet machines, but other problems at its fabs caused a relatively high number of its chips to fail, raising its emissions per chip.

“If you are throwing away 50 percent of your chips, you still have all the emissions but you are throwing away half of your profits,” said Techinsights’ Russell.

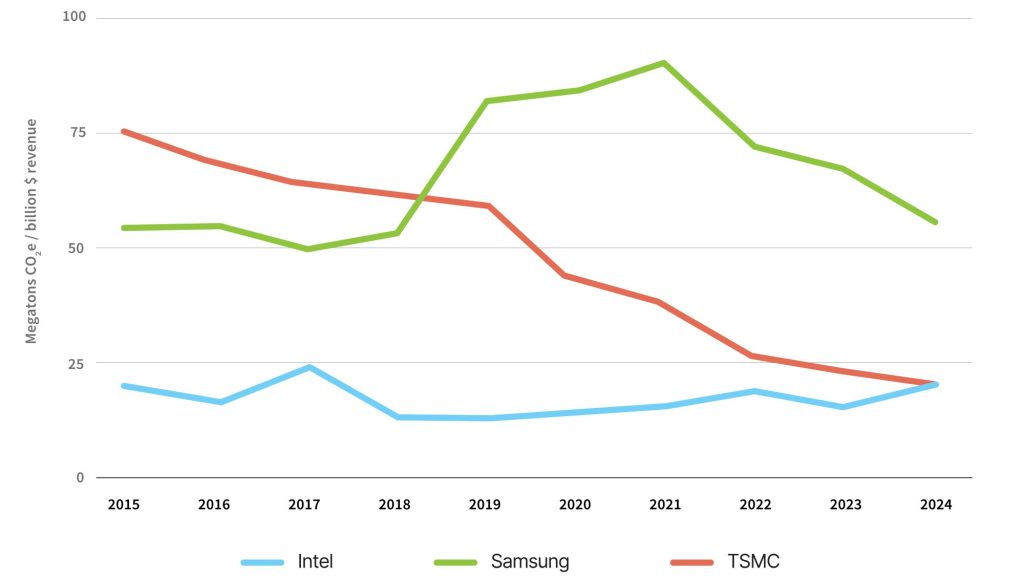

These factors help explain why rivals, which have been building new fabs, have seen their Scope 1 intensity — tons of emissions per dollar of revenue — fall: Samsung’s has dropped by a third since 2019, and TSMC’s by two-thirds. Intel’s intensity, by contrast, is up 56 percent.

Chipmakers’ Scope 1 emissions intensities

An Intel spokesman said that due to the complexities of semiconductor manufacturing technology, emissions intensity by revenue doesn’t accurately represent its performance.

On close examination, Intel’s most recent Scope 1 intensity may be even worse because it does not manufacture all the chips it sells. Two years ago, the company realized it couldn’t manufacture its most advanced designs and outsourced some fabrication to TSMC. Intel reports the emissions associated with making those chips the same way fabless companies do, as purchased goods and services in Scope 3.

Intel has shared limited details about the deal, but has said it outsources the fabrication of about 30 percent of its chips. If what Intel reported for Scope 1 in 2024 then represents only 70 percent of its sales, the company’s emissions intensity has more than doubled over five years. Intel declined to comment on this figure.

Intel’s renewables strategy hasn’t evolved

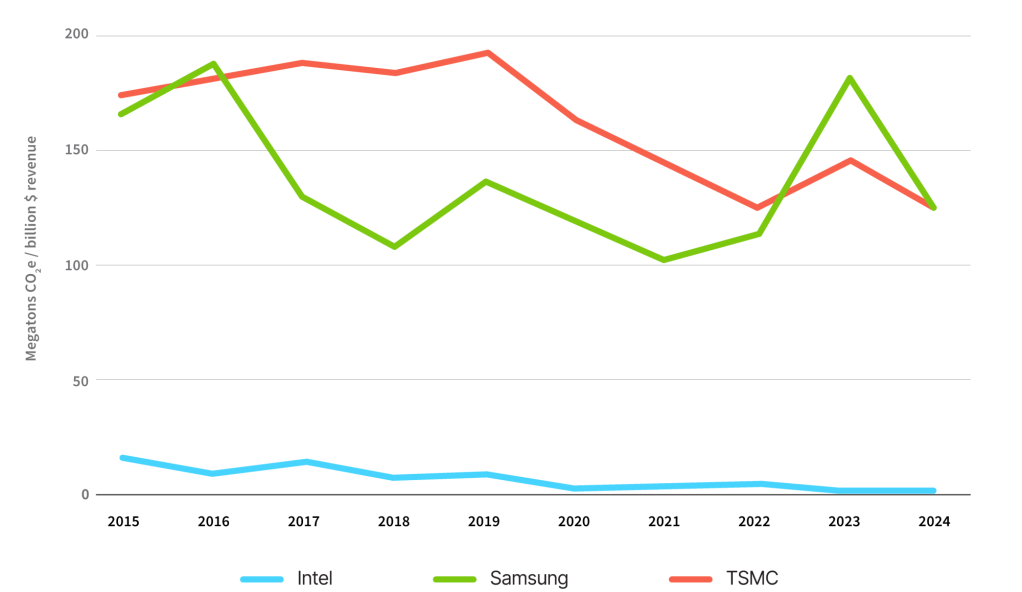

Intel’s business struggles haven’t obviously impacted its Scope 2 intensity numbers, which remain far superior to its immediate rivals. Five years into its 10-year commitment, Intel has exceeded its operational emissions target, largely by buying enough RECs to claim that 98 percent of its electricity comes from renewable sources. TSMC and Samsung operate in countries with grids dominated by fossil fuels —Taiwan and South Korea, respectively — and report significantly higher Scope 2 intensities.

Chipmakers’ Scope 2 emissions intensities

Still, Intel’s strategy hasn’t evolved in line with those of more forward-looking tech companies. RECs give buyers credit for clean energy projects that could be thousands of miles away, while the buyers’ own facilities may run on electricity generated by fossil fuels. That’s why Google and some others have developed more direct methods for linking renewable purchases with power use, which they say do more to decarbonize grids.

An Intel spokesman said that the approaches these other companies are using are not feasible in all of its locations.

Intel did install solar panels at a dozen facilities, but these produce well under 1 percent of its power. Meanwhile, other tech companies are also investing directly in clean energy. TSMC will buy the entire 960 megawatt output from 64 wind turbines Orsted is installing off the coast of Taiwan. And the need to power data centers for AI has prompted U.S. tech giants to contract for nuclear power.

Intel also appears to have less money set aside to pay for energy conservation. The company has committed to 4 billion cumulative kilowatt-hours of energy savings over the current decade, and says it has achieved 60 percent of that goal. But a 2022 promise to spend $300 million by 2030 on energy conservation has vanished from its public documents. In the first four years of the decade, it has spent $104 million on electricity-saving projects.

A Scope 3 target disappears

Intel’s commitment to tackling the roughly one-quarter of its emissions that stem from its supply chain has also waned amid its business troubles. Electricity use is the largest component, and many of the company’s vendors are in countries with limited renewables. Intel was a founding member of an industry group, coordinated by Schneider Electric, that is trying to arrange clean power for suppliers, but the group hasn’t announced its first deal yet.

Even harder is finding replacements for the greenhouse gases used to refine raw silicon into ultrapure wafers. For now, experts say semiconductor makers are pressuring suppliers to keep prices low rather than innovate on sustainability.

“I’ve talked to a lot of chemical suppliers,” said Julia Hess, a senior policy researcher at Interface, a German think tank. “They say we could put in more effort finding alternative gases, but we won’t do it until the large manufacturers ask for it because otherwise it’s not economically viable.”

It’s difficult to assess the effectiveness of Intel’s efforts to reduce supply-chain emissions. The company’s upstream Scope 3 total has doubled since 2019, but much of the increase comes from outsourcing production to TSMC.

What is clear is the company has eliminated any mention of its short-term supply-chain target — a 30 percent emissions cut by 2030 relative to business as usual — from its most recent corporate responsibility report. This year’s report, the first under Lip-Bu Tan, hired in March as CEO, omits this, referring obliquely to a “mid-decade refresh” of its targets.

“We’re sharpening our focus to drive deeper impact in the areas where Intel’s leadership can be most transformational,” wrote Head of Sustainability Madison West in the same report. “This streamlined framework allows us to act with greater clarity, agility, and accountability—while staying true to our core values.”

Giovanna Eichner, a shareholder advocate with Green Century Capital Management, said she was disappointed the supply chain goal went missing: “If they are having difficulty meeting their climate goals, that’s material information they should detail to investors.”

An Intel spokesman said that the company isn’t abandoning its efforts to reduce supply chain emissions, but the effort is now incorporated into its broader net-zero goal for upstream Scope 3, which has a target date of 2050.

The path forward: Business first

Climate change was hardly at the top of Tan’s to-do list when he was hired earlier this year. To staunch the company’s losses, he quickly announced plans to slash its workforce by a fifth. He also had to consider Intel’s relationship with President Donald Trump. The U.S. government now owns 10 percent of Intel, a deal Tan forged this summer after the president demanded he resign because of past ties to China. The man running one of Intel’s largest stockholders, in other words, is the world’s most prominent climate denier.

It’s not surprising then that Tan has said little about sustainability. But in addition to the dropped 2030 supply-chain goal, another clue about his priorities may be that Intel’s 2025 bonus plan, the first he has overseen, is not tied to reductions in Scope 1 and 2 emissions, as it had been in previous years.

Tan’s primary challenge, of course, is overcoming nearly 10 years of lost momentum in a fast-moving industry. Can Intel design AI chips as powerful as Nvidia’s? Can it operate fabs as precise as TSMC’s? And can it keep its unique position as a company that both designs and manufactures processors?

If Tan succeeds in revving Intel’s business, it will naturally help its climate efforts. New chips will be more energy efficient. New plants will capture more F-gases. The question then will be whether Intel will try to retake its position in the vanguard of companies addressing greenhouse gas emissions.

Intel’s struggles underline what can seem like a law of business: Combatting climate change is a laudable goal, supported by executives, employees and shareholders alike — but often only until times get tough.

“Sustainability, unfortunately, is an afterthought in most companies,” Russell said. “If things are going well, everybody is all for it. But profits come first.”

An earlier version of this article stated that Intel pushed back a 2030 goal for supply-chain emissions; the target was dropped rather than delayed. The article also stated that Intel no longer ties executive compensation to climate performance. This was overstated: the company no longer links compensation to greenhouse gas emissions, but has retained a link with renewable energy usage.

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders