The trials of making ‘dirt to shirt’ tees in the U.S.

Three decades after NAFTA destroyed his business, Eric Henry is growing and sewing this $60 organic T-shirt close to home. But it's not easy. Read More

- Efforts show how tighter, regional supply chains can reduce transport emissions and build resilience against global shocks — if buyers are willing to pay a premium.

- Geopolitical headwinds continue to limit progress toward sustainable domestic apparel production.

- Scaling beyond affluent consumers will require new infrastructure, investment and interest from brands.

Mass market T-shirts travel more than most Americans do. The materials in them commonly journey tens of thousands of miles from their cotton field roots to retail racks.

Less than 5 percent of clothes bought in the United States are made here, as 1.5 million jobs in apparel and textiles disappeared between 1979 and 2019.

Those who dream of renewed, home-grown supply chains have grasped for bright spots in the Trump administration’s chaotic storm of tariffs that have made it impossible for companies to conduct business as usual. Some advocates of slow fashion have found hope in the White House’s closure of a duty-free customs loophole that had favored fly-by-night fast fashions like Shein’s.

The secondhand clothing market may be an early beneficiary of such policies, but what about the few companies already making clothes from scratch domestically?

If anyone can answer that question, it’s T-shirt maker Eric Henry. His purpose-driven mission to source close to home has kept his Burlington, North Carolina, business afloat since the late 1970s. In 1994, however, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) almost broke his wholesale screen-printing outfit TS Designs, as customers like Nike bailed for cheaper suppliers overseas.

Local farm-to-fashion

Instead of collapsing, Henry drove harder into a sustainability niche, launching a Cotton of the Carolinas project that fosters “mini supply chains.” During the COVID-19 pandemic, he expanded that work into a retail brand, Solid State Clothing, to promote natural fibers and dyes derived from walnuts and marigolds. Scanning a QR code on the garment label opens a website of the faces, locations and contact details for each cotton farmer, fiber spinner and sewing operation.

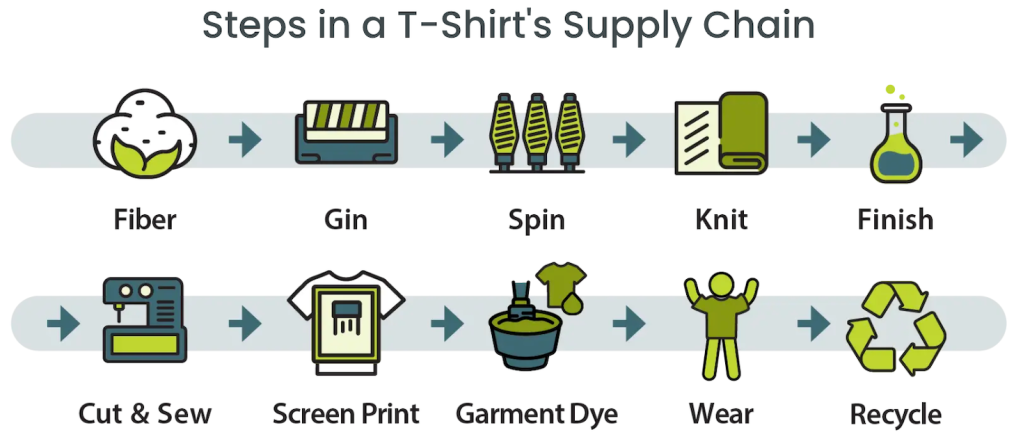

“I want to know the farmer,” said Henry (who has separately launched a collective of small farmers), of his new Where Your Clothing website. “I want to know the gin. I want to know specifics, because our industry is so good at greenwashing. It’s a way that we we check ourselves, and the consumer checks us.”

But decades into his labors to advance “dirt to shirt” production in the Southeast, Henry said hyper-fast fashion has brought the toughest challenges since NAFTA. And the powers-that-be in Washington are stripping away the supports that would help companies to revive U.S. manufacturing, and especially sustainable practices, according to Henry.

“At the end of the day, profits are important,” Henry said. “Making money is important. But I don’t want to do that if I’m hurting people or the planet.”

He has spent the better part of 2025 attempting to make sense of seesawing tariffs in order to afford the Spanish equipment he needs to build “the garment dye house of the future.” Meanwhile, federal funding for farmers’ sustainability and climate-related efforts is highly uncertain, with many programs delayed, canceled or at risk, impacting both Henry’s business and the broader supply chain.

“It just causes further chaos in the marketplace,” he said. In addition, Henry fears that farmers who already sell cotton abroad at a loss will struggle to attract buyers, due to the tariff “sledgehammer.”

Doubling down

Nonetheless, Henry is doubling down on his purpose. He wants to disrupt apparel brands’ sourcing by growing a manufacturing cluster in the Southeast. He insists that efficient, localized production will justify the price premium of his $60 tees for corporate buyers.

“Let’s talk about the apparel that you make that you never sell,” he said he will tell brands. “Let’s talk about the apparel that you make that you mark down. Let’s talk about how when something happens in the marketplace it takes you six months to respond. I can respond in a week.”

Local challenges

Henry offers an unusually granular level of transparency, but he isn’t the only maker pushing a U.S. farm-to-fashion model. American Giant of San Francisco sells its “Greatest American T-shirt,” spun from North Carolina cotton, for $65.

Imogene + Willie spent four years bringing to life T-shirts sourced and crafted within 400 miles of Nashville. The $56 white or black shirts are the fruits of its Cotton Project, which involved a seventh-generation farmer in Alabama, a third-generation spinner in North Carolina and a social enterprise garment shop in Tennessee.

And this fall, Renaissance Fiber of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, will start shipping its first-edition $55 hemp shirt, which is farmed in Montana and refined and knitted in the Carolinas.

“Each shirt is a wearable piece of history, a testament to American innovation, and a blueprint for a more resilient, sustainable and American-made future,” the company’s website states. The vision is romantic. In reality, local producers face numerous disadvantages relative to a corporate operation with in-house functions and shock-absorption capacity at scale.

Consider Henry’s latest year-long cycle to produce a batch of shirts from 1,000 pounds of cotton within 800 miles from home. It begins in spring, with seedlings planted by a farm in the Texas Organic Cotton Cooperative — among the last organic cotton producers in the nation. A nearby ginning operation then removed the seeds.

Ordinarily, Henry may have turned to the largest cotton spinner in the U.S., but the North Carolina company’s last domestic facility closed in 2024. Fortunately, North Carolina Spinning Mills was able to spin the fiber.

“Then the big fabric finisher, Carolina Cotton Works, in a 30-day notice went out of business last year and knocked a big hole in what we’re trying to do,” Henry said. Conveniently, the nearby knitter Henry chose, Beverly Knits of Gastonia, North Carolina, had snapped up textile finisher also in the state, Creative Dyeing and Finishing.

“Ultimately, we need the brands; they have the retail channels,” said Henry, who will be crowdfunding to buy enough Texas organic cotton for a later run of 15,000 shirts. “But we can make apparel manufacturing viable in this country, doing it this different way.”

Can more tight-knit, localized supply chains succeed in the United States? Or are these dirt-to-shirt efforts destined to be boutique brands that will only serve consumers who can afford 10 times the price of a mall or Amazon tee?

A threadbare industry

Margaret Bishop, a professor at the Parsons School of Design, is pessimistic about prospects for a meaningful revival of textile manufacturing in this country.

“Fifteen years ago, I said we could still successfully manufacture in the United States,” she said. “I no longer believe that we can on any significant scale.”

Americans generally don’t want to work in humid dye shops or mills, she said. And in addition to tariffs, the White House’s crackdown on undocumented workers is making even legal immigrants fearful to come to work in apparel jobs, she added.

Moreover, providing the variety of yarns and fabrics necessary to keep up with seasonal fashions requires the kind of specialization that no longer exists in the U.S.

“We don’t have the large fiber producers, the large weaving mills, the large knitting mills,” Bishop said. “We’ve outsourced it overseas.”

However, Bishop said, there may be domestic opportunities to produce specific goods such T-shirts, denim and specialized uniforms.

Regional manufacturing sites

Grey Matter Concepts, for example, is eyeing the Southeastern U.S. to build an AI-enabled factory to churn out socks and eventually T-shirts. The New York-based company sells its basics, including undershirts and boxers, to brands like Wrangler and DKNY.

The plant would offer roles for engineers and technicians with apparel and manufacturing degrees – a far cry from a sweatshop stereotype, according to Robert Antoshak, vice president of global sourcing. “I have this marketing image of people walking around in white lab coats: ‘Look at our socks, look at our underwear, our T-shirts.’”

Expanding some domestic production would bring sustainability benefits, according to Antoshak. For example, domestic cotton is easier to trace. “We can really tell a dirt-to-shirt story that’s U.S.-manufactured and -grown,” he said.

In addition to the momentum behind homegrown, natural fiber shirts, efforts are taking root to create circular manufacturing hubs for polyester. Goodwill Industries International of Rockville, Maryland, is partnering with polyester recycling venture Reju to supply secondhand fashion waste to transform into new textiles.

Said Goodwill CEO Steve Preston: “To the extent that we have these recycling facilities built here, it may not be that big of a step then to develop in that same region people who can spin that into yarn, rather than selling it and sending it to the other side of the world.”

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders