What buyers need to know about the surge of interest in methane credits

Independent experts say the interest of Google and other prominent companies is well-founded, but buyers still need to watch out for low-quality projects. Read More

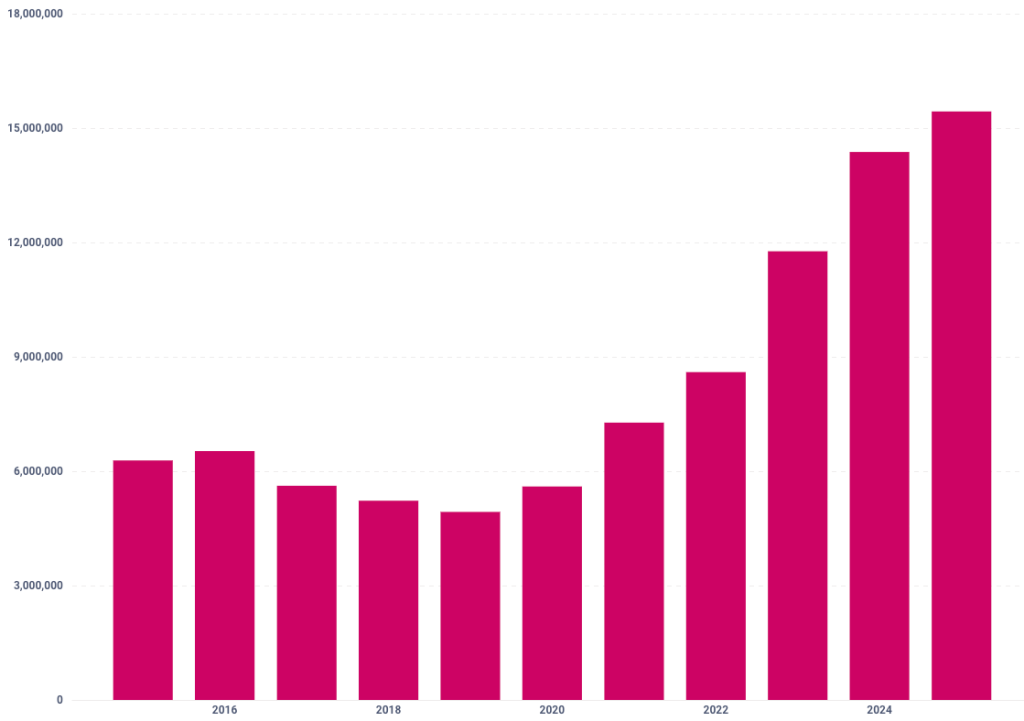

- Annual issuances of methane credits have tripled since 2019.

- The credit class is attractive because many projects avoid the quality problems that persist in other categories.

- Buyer beware: Independent experts have found examples of flawed projects.

Projects that prevent methane from entering the atmosphere are emerging as one of the fastest growing areas of carbon markets, with a surge in the number of credits being issued and interest from high-profile buyers such as Google and Netflix.

The attention is driven in part by the urgent need to capture methane, a potent greenhouse gas that the IPCC estimates is responsible for roughly a third of the global warming observed over the past century.

Methane is also an attractive focus for carbon credit funding. It leaks from sources like landfills, orphaned oil wells and disused mines that are relatively easy to tackle provided the funding is there. And compared with some other credit mechanisms, such as forest protection, project developers face a simpler task when it comes to estimating the climate benefits of their work.

Propelled by these factors and corporate demand, annual issuances of credits from methane projects have tripled to more than 15 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent since 2019, according to Allied Offsets, a carbon markets data firm.

Annual issuances of methane credits

Prominent examples include a purchase by Google of credits from a project that captures methane from a landfill in Cuiabá, Brazil, and enterprise software company Workday’s deal with Tradewater, a project developer that caps orphaned oil and gas wells. Netflix retired around 300,000 methane credits annually between 2022 and 2024, roughly 30 percent of the company’s total, according to the streaming giant’s sustainability reports.

The surge in interest is sparking other initiatives. Last month, for example, Vaulted Deep, a project developer that buries organic waste underground, said it would partner with Google and Isometric, a carbon credit registry, to develop methods for estimating methane emissions from organic waste.

The process is not well understood, in part because the waste can contain many substances. Putting a figure on it could boost the value of Vaulted’s credits, which at present are based on the quantity of carbon the company locks away in underground storage. This ignores the methane that would be released if the waste were spread on land or sent to landfill, as well as other impacts.

“Methane is a precursor to ozone, and ground-level ozone aggravates asthma,” said Bryan Epps, Vaulted’s head of commercialization. “It reduces crop yields, damages ecosystems and has all kinds of really significant negative effects.”

The range of methodologies open to project developers will also increase, with Isometric announcing this week that it will develop a new protocol for destruction of methane from landfills. “We’ve had really strong interest from major carbon removal buyers such as Google in bringing our scientific rigor and tech-enabled crediting into this important area,” said Lukas May, the company’s chief commercial officer.

Quality concerns

Due diligence on methane projects can feel relatively straightforward, in part because the projects are often clearly “additional” — meaning that the capture of the methane would not take place without the funding from credit sales. But independent experts caution against assuming that all methane projects are high quality. Calyx Global, a carbon credit rating agency, shared data with Trellis showing that methane projects assessed by the company are over-represented in high ratings, but many low-quality projects in that class exist nonetheless.

Quality ratings from Calyx Global

One flag for buyers to watch for is an on-off pattern in credit issuances. Last year, CarbonPlan, a nonprofit that studies climate solutions, looked at 14 landfill projects and questioned whether six were genuinely additional. The researchers found that the six stopped issuing credits for years at a time, but continued to operate methane capture equipment during those periods.

That the equipment ran continuously was good for the planet, the CarbonPlan team noted. “But offsets must be used to spur new climate action — not just reward existing actions.”

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders