No ‘fireball squirrels’: Nature and next-generation data center design

Lessons in nature and biodiversity restoration from Microsoft and Vantage Data Centers. Read More

- Community concerns over land conversion can kill data center development projects.

- Microsoft and Vantage Data Centers include nature and biodiversity improvements as part of their expansion strategy.

- Microsoft’s new AI chip design was inspired by the veins in leaves, a concept known as biomimicry.

The pipeline of U.S. data center construction projects has reached more than 500 sites and counting. With that boom comes a reckoning as communities in states from Wisconsin to Virginia scrutinize — and question — the heavy electricity, water and land requirements of what NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang has dubbed “AI factories.”

In early October, Microsoft retracted its plan to build on a site in Caledonia, Wisconsin, after local residents protested the potential conversion of agricultural land into an industrial site. The company will pursue development at another location in the state.

“One of the pieces of feedback that we heard was that the parcel was too closely situated amongst other residents,” said Kaitlin Chuzi, director of integrated technology and biomimicry at Microsoft, during a recent Trellis Impact 25 discussion about how to include nature and biodiversity in data center development decisions.

Engaging communities early is one of the best ways to address land-use questions and co-develop strategies for habitat restoration around new data centers or at other locations, according to the panelists. It starts with landowners and local officials who can connect companies with local conservation organizations to better understand community concerns.

“Really listening to what they’re hearing is a really helpful way for us to develop an understanding but also ferment some of the ideas about which types of work would be most impactful for the community,” said Emily Backus, sustainability director for North America at Vantage Data Centers, which operates campuses for hyperscalers, cloud service providers and other companies with large data center needs.

Another key stakeholder to include from “Day 0,” Backus said, are utilities. If a site requires new transmission lines, for example, that will dramatically increase the potential impact on nature and biodiversity.

Part of the plan

Data center companies such as Microsoft and Vantage have integrated habitat and biodiversity impact assessments and water studies into their standard design processes from the onset, especially as communities scrutinize a flood of data center site applications. Microsoft’s Chuzi, for example, reports to the company’s land management team; her role is not part of the sustainability office. Backus, on the other hand, collaborates closely with her company’s development engineers.

While there’s no typical land use requirement for data centers — and operators are encouraging increasingly higher server densities — hyperscale facilities can still require 200 to 500 acres.

Vantage uses unbuilt acreage to restore native habitats and encourage drought-resistant landscaping, eschewing turf or non-native plantings. By the end of 2024, it used this strategy at half of its site footprint, or about 4,000 acres.

One of Microsoft’s climate goals, set in 2020, was to protect more land than its operational footprint requires by the end of 2025. It has already met that pledge, with more than 15,849 acres permanently protected, as of its latest environmental report. Biodiversity remains a focus amid its furious AI-related expansion phase.

Biodiversity and ‘fireball squirrels’

Both Vantage and Microsoft embrace the philosophy of biodiversity net gain — the idea that development can make land more supportive for new species — to guide new projects.

Vantage, for example, used rain gardens, vertical greenery and other nature-based features to manage stormwater at its MPX2 campus in Milan, Italy, and restore the local ecosystem. It also planted multiple species of trees and flowering meadows at the campus. Where possible, given construction codes, it adds green roofs to data center buildings.

That could mean tradeoffs, however, from an emission standpoint, because more steel might be needed to support the weight of plants. Other tradeoffs include higher maintenance needs.

“The big question that my team and I have been talking about recently is whether it is worth it to put a green roof data center or, for the same cost, do ecological restoration on 100 acres off site,” said Chuzi. Her preference would be to do both.

Vantage will use a metric developed by consulting firm Ramboll to measure the impact of its North American projects, starting with two data centers in the Midwest. This was inspired by projects in the U.K., where demonstrating biodiversity net gain is mandatory for developers. This requires hiring ecologists who can perform initial and ongoing site evaluations.

“You think about all those green spaces around your buildings and your parking lots,” Backus said. “All of those are opportunities to do really significant improvements that can improve the biodiversity of those areas.”

Microsoft likewise looks for ways to add biological buffers and habitats to its campuses, a practice that was initially controversial with engineers, who were worried about squirrels and other rodents chewing through electrical lines.

“They have so many valid reasons for why you can’t bring nature closer to the technology that we’re bringing to the site,” Chuzi said. “I think my favorite one, and maybe the most memorable excuse was, ‘Kaitlin, you can’t put plants near the data center because we’re going to end up with fireball squirrels.’”

Much of Chuzi’s role involved balancing these concerns with biodiversity goals. The rodent problem, for example, can be addressed by encouraging habitat friendly to predatory birds that can help manage the population. A buffer can be established between plantings and crucial electric and transmission systems. And electrical systems can include additional insulation.

“It’s a lot of pulling together opposing ideologies and changing how people think about technology, how they think about nature,” Chuzi said.

Innovation inspired by nature

Nature is also reshaping design inside data centers.

Concerns about water, for example, inspired both Microsoft and Vantage to prioritize the installation of “waterless” cooling equipment that relies on outside air to dissipate heat or closed-loop systems that retain and recycle water.

Both companies are also looking for ways to funnel the heat generated by servers to places where it could be beneficial. Microsoft shares excess data center heat with a municipality in Finland, for example. That takes collaboration with neighboring sites, another reason community engagement is crucial for advancing data center development.

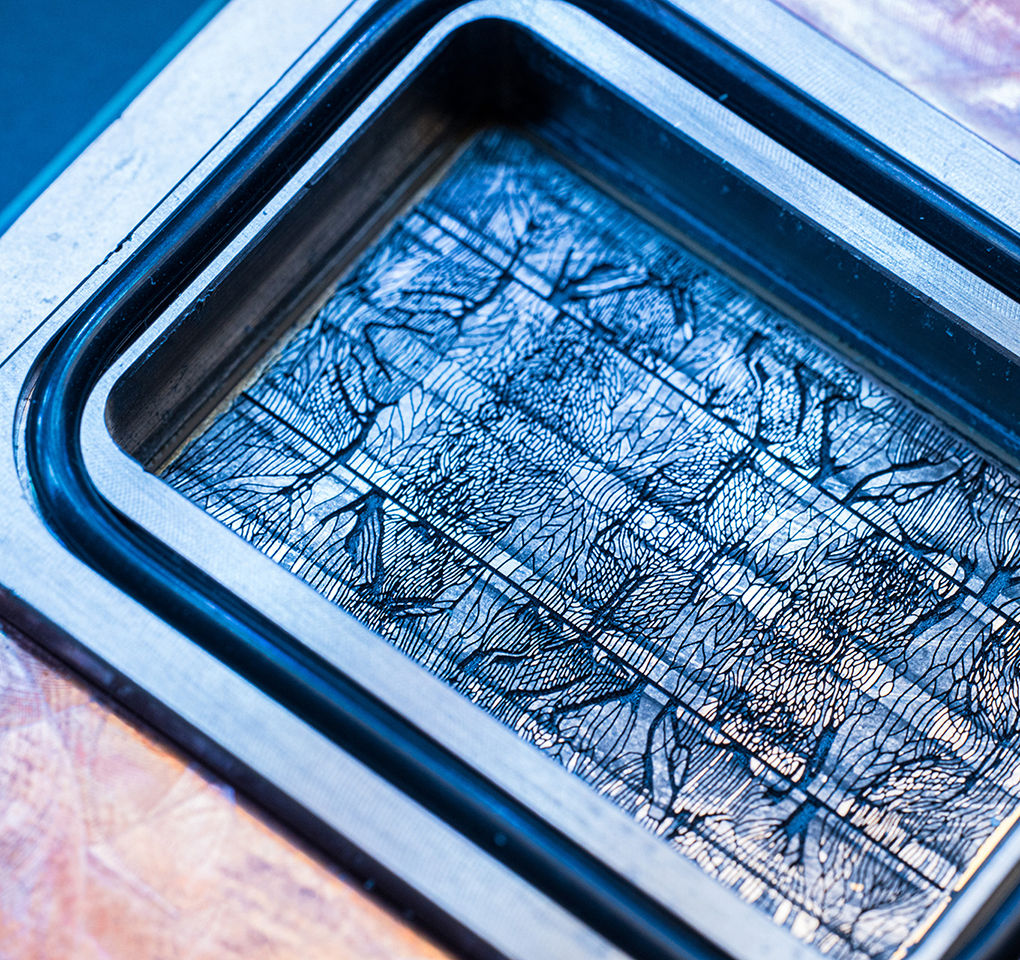

Nature was also the inspiration for a new AI chip design at Microsoft that uses a microfluidics approach to keep cool; the company says it is three times more effective than cold plates. Tiny channels move coolant through the silicon, much the same way that the veins of a leaf deliver water and nutrients.

These ideas all have roots in biomimicry, a discipline that reflects natural worlds in new product and systems design. Two of the most famous examples are Velcro, which was inspired by burrs, and the bullet train, which takes its cues from the anatomy of owls and kingfishers.

“If you start looking at data centers and how we design them through the lens of ‘How would nature do it in this place or how does nature solve problems like this?’ then you start to come up with really incredibly imaginative new designs that are better for the environment and better for the communities and better for the companies that are designing them,” Chuzi said.