Nestlé is on track to halve emissions by 2030. Here’s how (holes and all)

The food and beverage giant has achieved meaningful emissions cuts, but questions about its commitments remain — particularly around its use of carbon removals. Read More

- The Swiss company has reduced emissions by 20 percent since 2018, hitting its interim target a year ahead of schedule.

- Reducing methane emissions will be critical if it’s to reach its end-of-decade milestone.

- The company’s roadmap relies heavily on carbon removals, a strategy that environmental groups have questioned.

The 2024 emissions numbers released in February by Nestlé would have been the envy of many companies. The world’s largest food manufacturer’s first milestone on its journey to net zero — a 20-percent emissions reduction relative to a 2018 baseline — was due to be reached this year. But the Swiss company, which generates more than $90 billion in annual revenue through flagship brands such as Nescafé and KitKat, said it hit its target a year early.

Chasing Net Zero

For the first installment in Trellis’ Chasing Net Zero series — a company-by-company look at progress toward 2030 climate goals — we examined Nestlé’s emissions data and spoke with sustainability experts who have studied the company. Several praised Nestlé for its sustainability work, particularly its focus on agricultural emissions. But others raised concerns about its use of carbon removals, a central pillar of its decarbonization strategy. A review of statements made to investors raised additional questions about Nestlé’s future plans.

Compared to its peers, Nestlé has done much to earn its reputation; but the full story of the company’s journey to net zero is more fraught than its emissions data implies.

Track record

Nestlé’s net-zero target was validated relatively early — in 2020 — by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi). Five years later, many in the sector are still trying to catch up: Only 44 percent of the largest food, beverage and agriculture companies have net zero targets, and 23 percent have no target of any kind, according to the Net Zero Tracker, a data source maintained by four research organizations.

Other sector comparisons are similarly positive. In a benchmarking exercise released in May by Ceres, a nonprofit focused on the business case for climate action, researchers found that Nestlé was following several best practices that are rare in the sector, including setting climate requirements for suppliers. The company is also one of just three peers — with Campbell Soup and Danone — to have set targets for methane and other non-carbon dioxide agricultural gases in its supply chain.

The work behind this progress is overseen by Chief Sustainability Officer Antonia Wanner, a 24-year company veteran who moved from procurement into an ESG role in 2020 and joined the C-suite in January. Wanner and other leaders have short- and long-term compensation bonuses tied to emissions reductions.

Wanner’s boss, CEO Laurent Freixe, took the helm last August; his predecessor was ousted after what The Wall Street Journal described as “slowing sales growth and a slumping share price.” Nestlé stock has fallen slightly since Freixe’s arrival and is now down close to 30 percent from a January 2022 peak.

Nestlé’s biggest challenge: Scope 3

Like many other food and beverage companies, particularly those that source dairy and livestock ingredients, Nestlé faces an emissions challenge that is essentially a Scope 3 challenge: Of the 75 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent emissions (tCO2e) the company generated in 2024, 71 million tCO2e — 95 percent — stem from the company’s value chain. These include 13 million tCO2e of methane emissions from its ingredient sourcing.

Nestlé’s Scope 3 emissions have fallen steadily since 2021, the earliest year for which the company provided data in its most recent sustainability report, as have direct emissions from the company’s facilities and its electricity purchases. If progress continues at the current rate, Nestlé will achieve its goal of halving emissions by 2030.

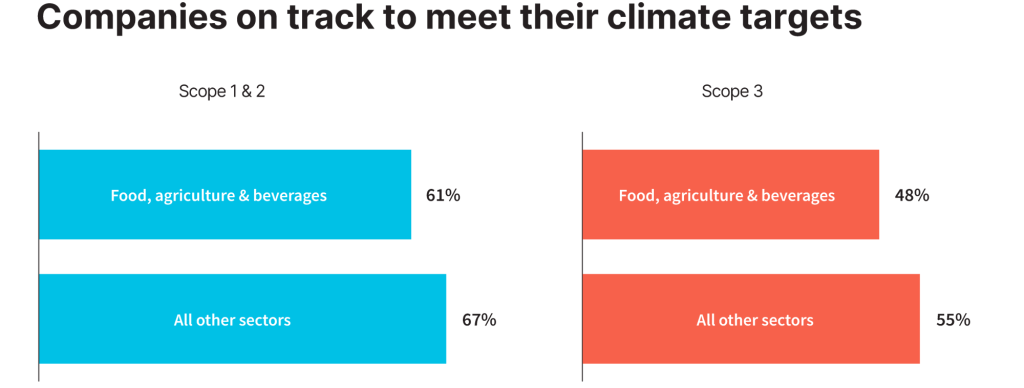

The reductions are notable given that decarbonizing dairy and livestock emissions ranks among the “toughest tasks” for food companies, according to David Linich, a sustainability partner at PwC. Linich declined to comment on Nestlé specifically, but a 2024 PwC survey of emissions disclosures shows that just over half the company’s peers are not on track to hit Scope 3 goals.

Nestlé has achieved these reductions using tactics that include training producers to improve the productivity of their farms, preventing deforestation in its supply chain and reducing methane emissions from cattle, according to its most recent Net Zero Roadmap, published in 2023.

Achieving the remaining cuts that Nestlé needs to stay on track for 2030 — notably lowering emissions from sourcing ingredients by 5 million tCO2e, were the company to reduce all greenhouse gases in proportion — will be challenging. The company is pursuing this on multiple fronts, including the use of food additives for cattle, which the company projects will reduce methane emissions by 3.2 million tCO2e by its target date.

Nestlé is also a member of the Dairy Methane Action Alliance, a collaboration between Ceres and the Environmental Defense Fund, which requires members to create action plans for reducing methane emissions. “We think Nestle is demonstrating that they’re putting plans and steps in place in order to make progress,” said Carolyn Ching, director for food and forests research at Ceres.

More uncertain: The role of removals

A second component of Nestlé’s past and future progress is more controversial. The company hit its 2025 target a year early in part because it removed 1.6 million tCO2e from the atmosphere in 2024 and deducted this figure from its total annual emissions. Nestlé did not break this total down, but removal mechanisms highlighted in its latest sustainability report include planting vegetation around water sources, no-till and other regenerative practices, and integrating trees into cropland.

The approach is particularly pertinent for Nestlé because the company’s use of removals will increase eightfold to hit 13 million tCO2e by 2030, according to its Net Zero Roadmap.

SBTi rules allow removals to be subtracted from total emissions in this way, but the practice has been contested because of uncertainties surrounding the reliability of nature-based removals. The science on the ability of soils to sequester carbon remains unsettled. Carbon stored in vegetation can also be released back to the atmosphere if farmers stop following regenerative practices.

“This is not a permanent emissions removal,” said Sybrig Smit, a policy analyst at the NewClimate Institute in Germany. “It’s going to be released into the atmosphere if the land is mismanaged.”

In an emailed response to questions from Trellis, Nestlé said it collects data directly from farms, including soil sampling and measurements of tree height, and places 20 percent of credits in a buffer pool to insure against losses. The company is also collaborating with Ofi, a major ingredients supplier, to monitor close to 3 million trees planted by 25,000 farmers in Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire and Brazil. Ofi said that a combination of remote sensing and machine learning enables it to track changes in carbon stocks at the farm level.

What Nestlé tells investors

Smit and colleagues at NewClimate, who studied Nestlé for recent editions of the organization’s Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor, question another removal line item in Nestlé’s 2030 plans: 6 million tCO2e the company subtracted from its anticipated 2030 total and attributed to “Portfolio transformation.” Tactics under this heading include switching to plant-based ingredients and “evolving our product offering to include more sustainable options.”

A Nestlé spokesperson declined to provide a detailed breakdown of where these cuts will come from, but did highlight recent implementations of this strategy, including with its Nescafé Alta Rica instant coffee brand. The emissions associated with each jar have fallen 11-14 percent since 2018, according to the Carbon Trust, an independent verifier of environmental projects.

Yet Nestlé has deemphasized its commitment to more sustainable products in at least some conversations with investors. A 2022 presentation at a Consumer Analyst Group of New York meeting, for example, included multiple slides on environmental issues and products; in this year’s presentation at the same event, CEO Freixe devoted just two sentences to the topic.

Given the Trump administration’s dismissal of climate issues and attacks on anything considered “woke,” this could be interpreted as prudent green-hushing. But Nestlé’s willingness to invest in sustainability, a metric that can be used as a proxy for a company’s commitment to emissions reductions relative to other priorities, is also unclear.

Nestlé does not share the amount it expects to invest in order to hit its 2030 target, but in a 2024 presentation to investors Freixe said that “we have done the heavy lifting” on sustainability and “we will need to continue to invest, probably at a lower pace” relative to the period up to 2025.

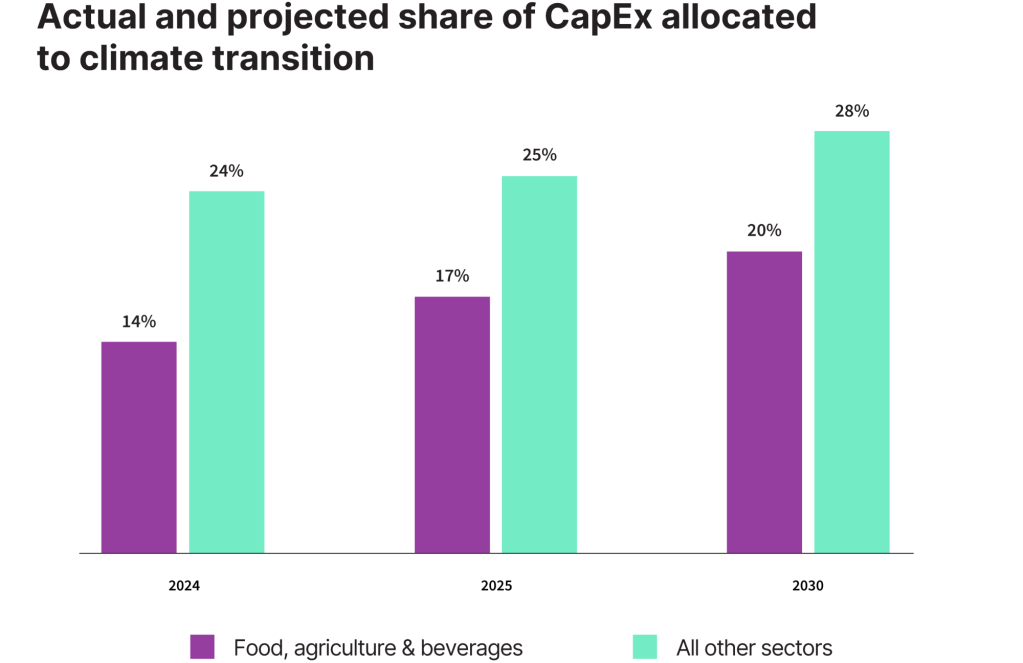

This stands in contrast to other food and beverage companies, which expect to increase the portion of their capital spending that goes to climate transition projects to an average of 20 percent by 2030, according to the PwC survey of emissions disclosures.

The next five years

To understand the complexities of Nestlé’s efforts to halve emissions by 2030, consider the position it now finds itself in.

On one side are investors, often more concerned with quarterly returns than long-term sustainability. Freixe’s “heavy lifting” comment, for instance, came in response to an investor analyst asking about the drag of sustainability initiatives on operating margins.

At the same time, the food sector likely cannot reach net zero without fundamental changes that no company can completely control. Decarbonizing would be easier, for example, if consumers swapped dairy milk for soy — but that doesn’t seem likely. Policy support is also an issue: one recent report found that current policies in the EU would decrease emissions by just 1.5 percent between 2020 and 2040.

These pressures leave Nestlé’s leaders with little room to maneuver. They’ve charted a course to net zero that is relatively transparent and ambitious, at least when compared with many sector rivals. At the same time, that roadmap is incomplete and relies on carbon accounting that’s open to question. As the climate crisis intensifies, these shortcomings leave critics of the world’s largest food company frustrated. They are also indicative of where the sector is on its journey to net zero.

Create your own user feedback survey