As plastics treaty talks enter the final round, here’s what to expect

As governments and stakeholders gather in Geneva, the outcome will shape global plastic policy for decades — and have ripple effects across supply chains. Read More

- This could be the final chance to secure a legally binding global treaty on plastic pollution, with major implications for business, regulation and supply chains.

- The most divisive issues are limits on plastic production, the phasing out of harmful chemicals and how implementation will be financed — none of which are yet agreed.

- Sustainability professionals should prepare now, as an ambitious treaty could trigger global changes to packaging, material use and extended producer responsibility obligations.

The plastics treaty talks that convened on August 5 in Geneva look like the last chance to deliver a meaningful global deal to stem the tide of plastic that is infiltrating our bodies, overwhelming our landfills and devastating our oceans. If successful, it would be the world’s first coordinated legal framework for tackling plastic pollution at scale.

If not? Well, read on.

The background

Launched in 2022 by the U.N. Environment Assembly, the talks seek a legally binding global treaty to end plastic pollution. The goal is to address plastics across their full life cycle — from design and production to use and disposal.

Negotiators have met five times so far, most recently in Busan, South Korea, in December. That session, meant to finalize the treaty, collapsed without agreement on a single article — including the treaty’s objective.

Where are we now?

The current “Chair’s Text” — the draft agreement guiding negotiations — reflects a deeply divided process. Though it includes measures to improve waste management, on the whole it avoids the most controversial issues: limits on plastic production, regulation of toxic chemicals and how to pay for it all.

“There’s a clear majority of countries that have made statements committing to strong measures on chemicals of concern and limiting the production of plastics,” said Sam Winton, a researcher studying the treaty process who is attending the talks. “But there are a small number of countries that consider those topics completely out of the scope of the Treaty.”

This resistance comes primarily from oil-producing nations — reportedly led by Saudi Arabia and including Russia and Iran — and plastic-exporting economies that want to focus only on downstream solutions, such as recycling. Meanwhile, ambitious countries — including coalitions led by Rwanda and Mexico — are pushing for upstream controls and legally binding global targets on the use of harmful chemicals and products.

Following a July meeting in Nairobi, the Trump administration issued a statement opposing production limits: “We support an agreement that focuses on efforts that will lead to reducing plastic pollution, not on stopping the use of plastics.”

Reuters reported on Aug. 6 that the U.S. team has been urging at least a handful of countries to reject an agreement that places limits on plastic production and chemicals of concern. Opposing “provisions related to the supply of plastic, plastic production, plastic additives or global bans and restrictions on products and chemicals,” the stance puts the U.S. at odds with over 100 countries that support an agreement with a scope beyond waste management.

What’s at stake?

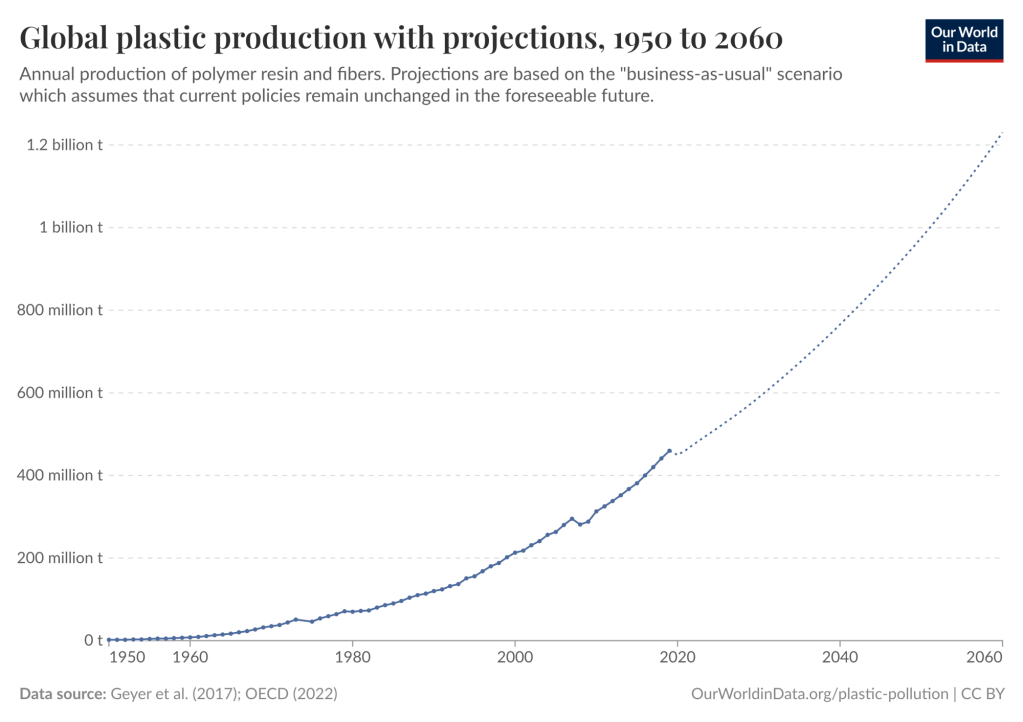

Over 460 million metric tons of plastic are produced annually, of which 20 million end up in the environment. Plastics contaminate virtually every ecosystem on Earth, driving biodiversity and ecosystem loss. Globally, the production, use and waste management of plastics is responsible for 4 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions.

But this treaty is about more than environmental protection. It could reshape markets, supply chains and regulations for years to come.

For businesses, an agreement would mean:

- Tighter rules for plastic packaging and product design

- Restrictions on hazardous chemicals in plastic goods

- A global push toward reuse, refill and alternative material

- Increased costs through extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws, such as those in California, Colorado and five other states

What will Geneva focus on?

The Geneva session will center on four unresolved issues:

Scope and ambition

Will the treaty cover only waste or the entire plastic life cycle — including how much plastic is made and how? The current draft leans toward a voluntary, national-level approach. Many countries say that’s not good enough, and that a global, enforceable agreement is needed.

Plastic production

Proposals include setting global targets to reduce the production of primary plastic polymers. Petrochemical-producing nations strongly oppose this, seeing plastics as a growing market for fossil fuels in a world in which demand for energy production will fall in the coming years.

Chemicals and products of concern

More than 16,000 chemicals are used in plastics, many with unknown health effects. Some countries want to begin phasing out the worst offenders. Others — including industry groups — oppose these moves, citing cost and supply chain complexity. Specific chemicals of concern won’t be decided at these talks, but negotiators could agree to begin to develop a list ahead of future meetings.

Finance and implementation

Developing countries such as the Philippines, with weak to nonexistent recycling systems, want support to implement the treaty, including technical assistance and a dedicated funding mechanism. Wealthier countries prefer to work through existing platforms such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Who pays — and how much — remains unresolved.

What are the possible outcomes?

There are four broad scenarios for how the Geneva talks could end:

- Low ambition: A weak treaty focused on voluntary, national-level waste measures. This would be relatively easy to reach but risks being ineffectual.

- High ambition: A legally binding global treaty covering chemicals, product bans and production limits, along with a roadmap for implementation. This is what many countries want, but it faces stiff opposition in certain quarters.

- Middle-ground package deal: The most likely scenario: a compromise that trades stronger commitments in one area (such as chemicals) for softer language in another (such as production). Behind-the-scenes negotiations will be key to achieving this.

- No agreement: If talks fail entirely again, the process could collapse. That could cause some countries to pursue separate high-ambition treaties outside the U.N. Others may fall back on national or regional regulations — creating a patchwork of compliance risks for global businesses.

Why this matters

The treaty’s outcome will set the direction for plastic regulation, innovation and compliance over the next two decades. A robust agreement would accelerate the shift away from single-use plastics, force businesses to rethink packaging and material choices and create new reporting and transparency requirements across supply chains.

Even companies not directly involved in plastic production would face new obligations as part of EPR schemes, product bans or chemical phase-outs.

“It is very likely that an ambitious, successful treaty will impact various parts of your operations, probably some parts that you haven’t already thought of,” said Winton.

This story was updated on Aug. 8, 2025 with further detail on the U.S.’s position.

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders