These 5 companies hope to spin old polyester threads into fashion gold

Like many startups in the space, they are forming waste-based supply chains, one partner at a time. Read More

- Scaling true textile-to-textile systems is essential to meet circularity goals and decouple fashion from fossil fuels.

- Strategic partnerships with brands, waste collectors and fiber spinners are must-haves for success.

- With varied technologies, regional supply chains and brand needs, the future of polyester recycling will likely rely on a diverse ecosystem of players.

Nearly every week brings another brand partnership, factory blueprint or financing deal related to a polyester recycling startup. The space is crowded with young companies seeking to weave together a circular economy that pushes virgin polyester to the margins.

In a few short decades, polyester has displaced cotton as the dominant fiber. It’s found in nearly two-thirds of new fashions. Because it’s made with cheap fossil fuel byproducts, however, the apparel industry’s emissions shot up 7.5 percent in 2023 after a modest dip, according to a June report by the Apparel Impact Institute. As a result, the industry accounts for almost 2 percent of all the world’s climate emissions.

Brands striving to reduce that impact, along with its regulatory and operational risks, plan to procure more recycled and “next-generation” materials. So far, only 12.5 percent of polyester comes from recycled sources, 99 percent of which begins as bottles rather than textiles, according to the Textile Exchange.

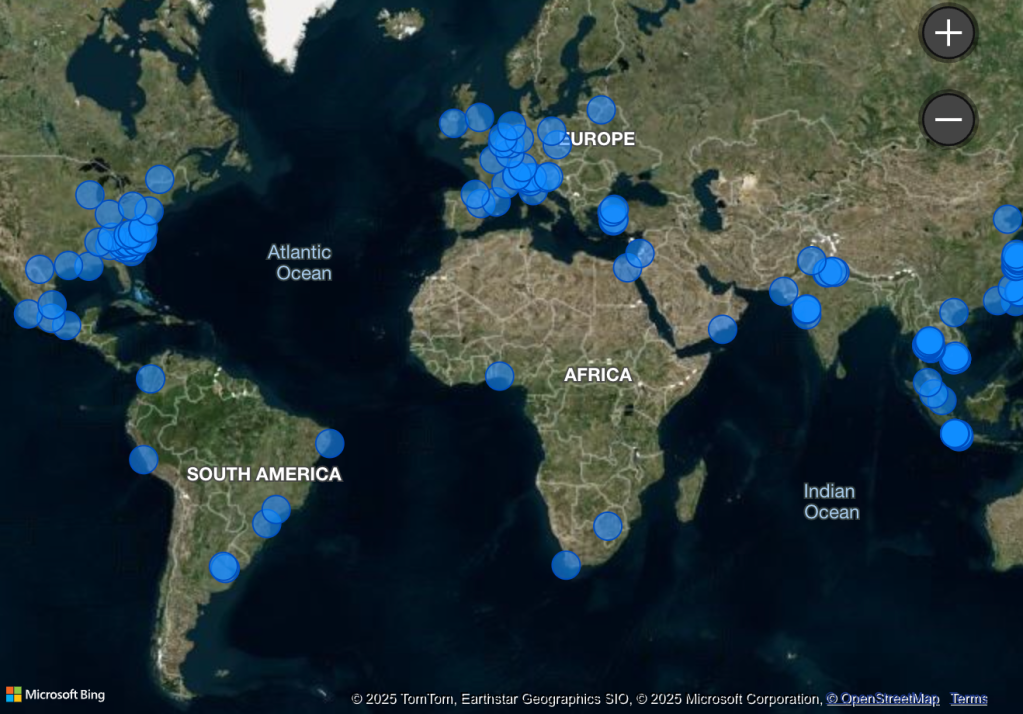

Where Polyester Is Made

It’s no easy feat to court partners in a new, waste-based supply chain within the fragmented textile industry. To begin with, a startup needs an efficient technology to transform unwanted fabrics into something new. It must also procure and sort castoff garments or factory clippings from third parties. Once the buttons, trims and zippers are removed, the material needs to be recycled into a raw output, such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) pellets. Yet another partner spins that into fiber, which someone else turns into a textile for a brand.

The final leg in this process: efficient factories. “Ramping to full capacity, which they must operate close to if they are to at least break even, is the big challenge,” said Marcian Lee, an analyst with Lux Research.

Textile recycling executives insist that there’s room for multiple players to spin old plastic threads into valuable textiles. Here’s how five of them are seeking to bring a textile-to-textile recycling system to life.

Circ

Circ is building a $500 million plant in northeastern France. Scheduled to open in 2028, it would be the largest industrial polycotton recycling operation.

Many synthetic recycling startups say they accept textile blends, including polyester-cotton, to produce material for fresh polyester fibers. Circ distinguishes itself by recycling the cotton, too.

“You’re really maximizing the economic value of what’s in that starting material,” Conor Hartman, Circ’s chief operating officer, told Trellis in May. “We’ve taken polycotton originating material and made it into beautiful lyocell products and beautiful polyester products.”

Circ’s recycled cellulosic lyocell appeared in a small collection last month from Zalando, which is an investor, as are Patagonia and Inditex. Circ recently inked deals with fiber producers, too, including China’s Tanshan Sanyou and Portugal’s Selenis.

Earlier this year, Circ kicked off Fiber Club, a collaboration to scale recycled fibers that Bestseller, Eileen Fisher, Everlane and fiber producers support. Such bridge-building follows the Circ-Ready community launch of partners a year ago.

Virginia-based Circ has attracted $100 million of investment, the most recent coming in 2023 via a Series B raise of $25 million.

Ambercycle

Ambercycle has partnered with Reformation, Arc’teryx and Gap’s Athleta as well as important textile and polyester companies in North America, Europe and Asia, including Shenghong Holding Group and Zhejiang Huilong New Materials of China.

In January, the startup secured an offtake agreement to replace about 20 percent of Danish brand Ganni’s polyester usage. That follows a three-year, $80 million offtake agreement with Inditex in 2023 and another binding deal with brand Mas.

“We’ve tried to piece together the pathway to get to this commercial scale, because the challenge with us and really everyone in this space is that, out the gate, the competition with existing fibers is pretty significant,” CEO Shay Sethi told Trellis in June.

Ambercycle is developing an enzymatic recycling feature that would allow a multi-fiber output, enabling brands a “one-stop shop” if they want specific blends of, say, polyester, nylon or spandex, according to Sethi.

Last year, Taiwan’s Shinkong Synthetic Fibers provided $10 million toward a commercial plant for Ambercycle, expected to open in 2026. Ambercycle, whose pilot plant has been running in Los Angeles since 2022, has raised $56 million in its 10 years.

Sethi envisions an industry that balances both centralized operations and regional production. “With textile waste, for better or worse, there’s no shortage anywhere you look,” he said.

Reju

With offices in Paris, Reju piggybacks on its Dutch parent Technip Energies, which counted $6.9 billion in revenues last year. The umbrella company’s resources in engineering and chemicals include polyester production.

Reju’s pilot plant in Frankfurt opened 20 months ago. Next, a large-scale factory planned for the Chemelot industrial park in the Netherlands would recycle 300 million polyester garments each year by 2027.

European Union rules that require brands to take responsibility for their textile waste provide a boost, but Reju is eyeing “regeneration hubs” elsewhere, too. It hooked up with Goodwill and Waste Management last fall to lay a foundation in North America.

Reju uses IBM’s VolCat technology, short for volatile catalyst. “We’re dealing with known chemistry here,” CEO Patrik Frisk told Trellis in May. “Part of what makes polyester so easy for the textile industry is, first of all, the infrastructure for it has been thoroughly developed over the last 70 or 80 years.”

That frees up Reju to build out its circular system, according to Frisk, former CEO at Under Armour. Despite its problematic origins and contribution to microplastic waste, the material is endowed with useful properties and thus here to stay, he said. “We’re able to take away all the stuff that’s bad, and create new again.”

By giving the waste a second life, Reju can potentially design materials that shed fewer microfibers, Frisk added.

Samsara Eco

With machine learning, Samsara Eco customizes enzymes that “eat” polyester. Last year, it proved it can do the same for nylon 6,6. The result appeared in a long-sleeve Lululemon top. In June, the startup established a decade-long offtake agreement, vying to provide potentially one-fifth of Lululemon’s overall fiber portfolio.

In addition to creating a $25 million R&D hub in Jerrabomberra, Australia, Samsara Eco is working with Israeli nylon producer Nilit on a recycling plant to open next year in Southeast Asia, home of partner waste suppliers.

“But that will only be the first of our facilities where we’re talking closely with polymerization partners in Europe and in North America as well across better packaging and fashion,” CEO Paul Riley told Trellis last winter.

Samsara Eco has raised $107 million. It aims to give new life to 1.5 million tons of plastics annually by 2030. That’s less than half of 1 percent of global plastic production each year, leaving plenty of room for multiple recyclers, Riley suggested.

“We’re looking at infinite recycling, true circularity across fashion and packaging,” he said, “and an important thing to note is that there is no difference between our molecule and a fossil fuel molecule. We tap straight into the supply chain.”

Syre

Syre in June touted strategic deals to supply Gap, Target and Houdini Sportswear with its chemically recycled polyester, which it says carries only 15 percent of the CO2-equivalent footprint of the virgin standard. Gap alone would use 10,000 metric tons of Syre’s output annually.

First, though, Syre has to break ground on the 12 commercial scale plants it originally announced for late 2026.

Before it even had a demo facility, Syre had an eye-popping $600 million promise of seven years of support from co-founder H&M. The Swedish startup’s long-term end is to recycle at least 3 million metric tons of polyester each year.

Syre is colocating a pilot plant in North Carolina with a Selenis polyester production facility. It has the ambition to bring “gigascale” plants to Vietnam and Iberia in the next few years. “This is the start of the great textile shift,” Syre CEO Dennis Nobelius told Trellis in June.

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders