How AI forced Salesforce to reset its 2030 climate goals

The $38 billion enterprise software company pivoted on its emissions plan and set a target it looks likely to reach as early as next year. Read More

- Salesforce’s new target is based on cutting emissions per unit of profit, rather than absolute emissions.

- The move is one of several tactics that fast-growing software companies are using to deal with a surge in AI-related emissions.

- Using cloud services provided by larger tech companies will be key to Salesforce hitting its new target.

Like many fast-growing companies betting on artificial intelligence, Salesforce is pacing far behind its climate action plan.

The $38 billion enterprise software business said in 2021 that it would halve absolute emissions by 2030. Four years later, the company can point to solid progress on cutting emissions from electricity use. But those gains have been entirely canceled out by emissions growth elsewhere, including in the data centers that power its AI products.

Chasing Net Zero

Against that backdrop, the company has dramatically shifted how it intends to cut the biggest part of its carbon footprint. In the latest installment of Chasing Net Zero, our in-depth series that includes profiles of emissions progress at ArcelorMittal, Nestlé and GSK, we unpack the forces behind the move and explain why some observers are asking whether the switch has weakened Salesforce’s ambition on climate action.

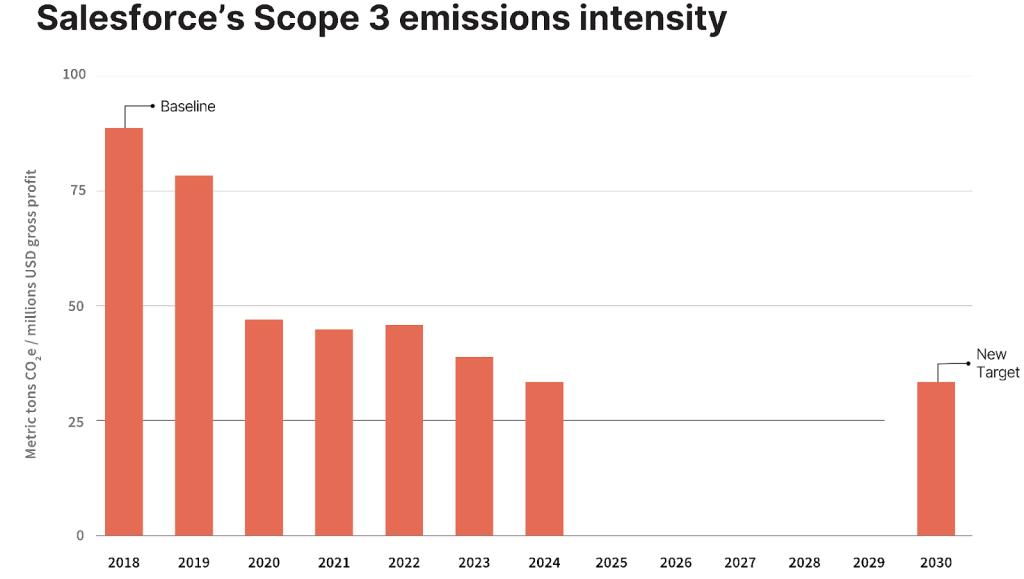

Salesforce is now basing its Scope 3 target — which includes data centers and other sources outside its immediate control, such as goods from suppliers — on improvements to emissions intensity rather than absolute reductions. Using this measure (Scope 3 emissions divided by the company’s gross profit) leaves open the possibility that the company’s absolute emissions could increase even if it meets its goal.

What’s more, an analysis by Trellis of the company’s new intensity commitment suggests it will likely hit its goal just a year after setting it, raising questions about the depth of its ambition.

Salesforce describes its decision to lean into emissions intensity, outlined in its most recent stakeholder impact report, as a “more actionable and pragmatic” route to net zero. “For a high-growth company like Salesforce, this approach is more practical given that growth may outpace the global rate of decarbonization,” said Sunya Norman, senior vice president of impact.

Leadership legacy

Salesforce became one of the earliest companies from any industry to embrace net zero when co-founder and CEO Marc Benioff signed a splashy 2015 pledge organized by fellow billionaire Richard Branson.

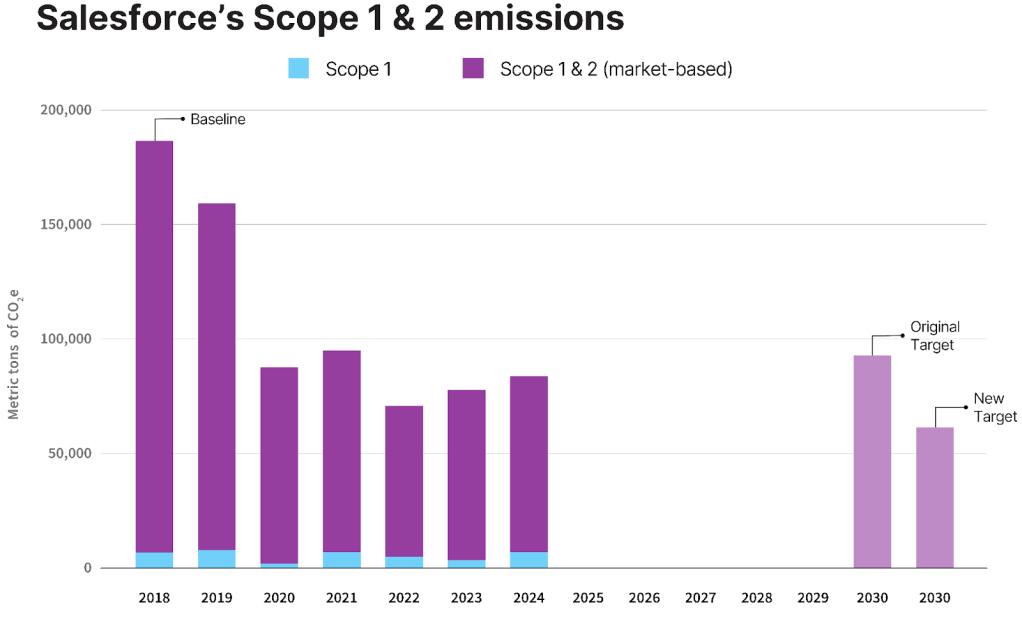

Its initial plan, validated by Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) four years later, called for halving emissions from operations and electricity use (Scopes 1 and 2) by 2030 — a commitment Salesforce achieved several years early thanks to investments in renewables. Subsequently, it has upgraded to a more ambitious 2030 target for Scope 1 and 2.

The 2019 plan also targeted a 50 percent cut to emissions from use of fuel and energy elsewhere in the company’s value chain. In a 2021 climate action plan, Salesforce expanded that commitment to all upstream and downstream Scope 3 emissions, including electricity consumed by data centers that run its software, but which the company doesn’t own. (The company did not have that broader pledge validated by the SBTi.)

To shrink its biggest emissions source — purchased goods and services, including the cloud capacity it sources from Amazon Web Services and Google — and meet a 2019 goal of having 60 percent of Scope 3 emissions come from suppliers with science-based targets, the company uses contracts that require strategic suppliers to cut emissions. Salesforce also turned its climate strategy into a source of business, packaging the system it built to track its emissions into a product called Net Zero Cloud, priced at $210,000 annually.

Yet progress on overall emissions has been a victim of financial success. Since setting its first science-based targets, Salesforce has acquired data analytics software provider Tableau and messaging software firm Slack. It’s also merged with AI management player Informatica. The moves helped triple revenues — and contributed to absolute emissions staying stubbornly flat.

In 2024, the company’s emissions were just 1 percent below its 2018 baseline inventory of roughly 1 million metric tons. While the company reached its 2030 reduction goals for Scope 1 and 2 two years ago, overall emissions from Scope 3 activities — which made up more than 90 percent of its 2024 emissions — swelled 10 percent between 2019 and 2025. The company also fell short of its Scope 3 fuel and energy use goals, as well as its supply chain coverage goal.

Reboot required

Salesforce undertook a cross-company review in 2024 to reconsider its science-based targets as part of SBTi’s five-year review requirements. It dedicated a data scientist to analyzing progress and forecasting future scenarios, using internal metrics such as headcount adjustments, expansion plans and revenue projections alongside third-party data including grid decarbonization forecasts.

The company’s market-based reduction targets for Scope 1 and 2 are now more ambitious: A 67 percent drop by 2030, compared with the 50 percent reduction previously sought and already delivered, followed by a 90 percent cut by 2041.

But it’s in Scope 3, which contributes the large majority of Salesforce’s total emissions, where things get more complicated. Instead of another absolute goal, the company is targeting emissions intensity cuts of 68 percent by 2031 and 97 percent by 2041.

Around 80 percent of companies with SBTi-approved plans have absolute reduction goals — and this method is what many investors and stakeholders expect. Still, the initiative’s Corporate Net Zero standard allows Scope 3 intensity goals in high-emitting sectors where growth is projected to be sector-wide and significant.

Salesforce is not the first tech company to make the switch: Design software firm Adobe opted for a Scope 3 emissions-intensity target when it updated its commitments in August 2024. Other well-known software developers are considering this option as part of the near-term target reviews that the SBTi requires every five years, according to insiders.

The megatrend underlying this thinking: Predictions of soaring energy use in AI data centers, which could consume 12 percent of all U.S. electricity by 2028. That’s driving an uptick in natural gas plant construction and is one reason why the three biggest software companies racing to claim AI leadership — Amazon Web Services, Google and Microsoft — have all seen recent increases in emissions.

“You could view these economic intensity targets as a way of managing emissions in the short term as we are waiting for mitigation technologies to scale,” said Emma Armstrong, executive director for North America at consulting firm Anthesis. “They can be challenging to achieve and, for most companies, will require a very meaningful decoupling of emissions from growth.”

Both of Salesforce’s new goals for emissions intensity are above the minimum required by SBTI, Norman said. “The way to think about our [old] targets versus our new targets is these Scope 3 targets are much more comprehensive, and they’re completely aligned to science-based target methodology that didn’t exist five years ago,” she said.

The idea of emissions intensity often resonates with business leaders outside the sustainability function, said Armstrong. “Ten years ago, companies could set a target, it could be very ambitious, but there was less high-level scrutiny,” she said. “Those days are 100 percent gone. You cannot take a target to senior management unless you can tell them exactly what you’re going to do to deliver.”

Easily achievable goal

How likely is it that Salesforce will reach its new near-term pledges?

The company won’t start officially publishing its new metric until next year’s impact report. Trellis analyzed Salesforce’s emissions intensity since its baseline year using historical emissions and gross profit data.

Those calculations show that the company reduced its intensity by 62 percent since 2019, suggesting Salesforce is already close to its near-term goal. Indeed, if it maintains the pace of reductions seen in recent years, the company could hit the goal in 2026. What’s more, if its cumulative gross profit grows more than 50 percent over the next five years, Salesforce could meet its intensity goal and still report an absolute increase in Scope 3 emissions.

When asked to comment on the level of ambition for the emissions-intensity goal, Norman noted that the new, near-term SBTi-validated target is more comprehensive than the one it replaces, which covered just one category of Scope 3. “We are aligning to this metric in line with SBTi guidance and above their minimum requirements,” she said.

Emissions intensity targets focused on metrics, such as the energy used in production, are valuable for specific commodities, as they can serve as industry benchmarks, but ones pegged to profit are less meaningful, said Thomas Day, a climate policy analyst at the NewClimate Institute, which analyzes company emission commitments in its Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor.

“The only stakeholder group that I can see benefiting from such an approach is investors that are not actually interested in the company decarbonizing, but rather just want to know that the company has the profit margin to absorb any potential regulation related to carbon pricing that may come along in the future,” he said.

How Salesforce plans to make progress

AI has swelled Salesforce’s addressable market from billions to trillions of dollars as it enters its 26th year. Its technology, Agentforce, uses autonomous agents to automate tasks such as nurturing sales leads, and to offer tips on how to close a deal.

“This is not just a technology shift, this is a shift in how work gets done,” noted Salesforce CEO Benioff this year. The company has publicly committed at least $1.5 billion to fund AI innovations.

Salesforce is also at the forefront of industry-wide efforts to define priorities for “sustainable AI” and evaluates its own AI investments with sustainability in mind, beginning with this question: Is the application really warranted?

“The first part of the strategy starts with acknowledging that not every business activity needs to be replaced with or augmented by AI,” said Norman. From there, the company cuts power use by prioritizing the efficiency of its AI code and reducing the size of data sets used to train its algorithms.

But it’s the company’s approach to technology infrastructure that will be the most crucial factor in mitigating AI-related emissions. In recent years, data centers represented an average of 19 percent of Salesforce’s total market-based emissions. To reach its new targets, Salesforce needs to cut the absolute emissions from suppliers and data centers by 13 percent and 10 percent, respectively, alongside measures to tame business travel and the footprint from its offices.

Unlike two big competitors, SAP and ServiceNow, Salesforce doesn’t host applications in its own data centers. Rather, it runs them on a combination of equipment co-located in bigger data centers owned by partners, such as Digital Realty, and on cloud computing services managed by Google and Amazon Web Services.

That hybrid approach could be a big advantage, because Salesforce leaders estimate that economies of scale make cloud data centers 40 percent more efficient than co-located infrastructure. Studies by big cloud providers offer a similar narrative: Microsoft, for instance, claims its Azure platform is 98 percent more efficient than a bespoke approach.

Salesforce also plans on leveraging its status among the top five enterprise software companies to motivate emissions cuts by its big cloud and infrastructure partners. More than half of Salesforce’s strategic suppliers have agreed to emissions cuts in their contracts. These are “super strategic relationships that need to have sustainability as part of the broader conversation,” Norman said.

Salesforce’s contract structure — still unusual in any industry — is a real advantage as the company tackles its “massive” Scope 3 target for 2040, said Jennifer Vieno, ESG research director for technology, media and telecommunications with Morningstar Sustainalytics. In particular, it makes it easier to see what strategies actually have an impact, she said.

Executives hope these efforts will help Salesforce navigate the transition every software company with net-zero commitments is confronting. While three of the biggest players in AI infrastructure — Amazon, Google and Microsoft — are sticking by original commitments, their emissions have skyrocketed, forcing all to rethink sustainability strategies. Microsoft, for instance, has said it will retire millions of carbon credits annually to meet its goal. Against this backdrop, Salesforce’s decision to revise its approach can be viewed as a pragmatic way to manage emissions amid a period of growth.

“We believe that intensity-based targets can be a useful tool,” said Kelly Poole, energy and climate coordinator with nonprofit As You Sow. “In general, they are trying to take accountability for Scope 3 emissions. I do see them as playing an active role.”