Inside Seventh Generation’s playbook for supporting polluter-pay laws

Next in the consumer product company's sights: California legislation that would assess fees on the world’s largest fossil fuels producers. Read More

As the Trump administration wages a multi-front attack on federal environmental policies, Seventh Generation is stepping up its advocacy and defense of state laws that require polluters to pay for the negative impacts of climate change.

The cleaning products company, known for its bio-based formulations, was a prominent supporter of Vermont’s Climate Superfund Act, which became law in May. Prior to the passage, the Burlington-based company joined 60 local businesses, including Ben & Jerry’s, to support the bill by meeting lawmakers and through grassroots outreach designed to build public awareness.

Seventh Generation was also part of a business group that worked for more than a year to get similar legislation passed in New York in December. Now, the company is focusing on California, where lawmakers have revived a climate superfund bill that failed to pass last year, while staying abreast of similar bills in Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Oregon.

“Some of the most ambitious and just policies on climate have been advancing at the state level,” said Kate Ogden, head of advocacy and movement building at Seventh Generation, a subsidiary of Unilever. “We can have the greatest impact there.”

Make policy advocacy an integral piece of climate strategy

Ashley Orgain, chief impact officer at Seventh Generation, said all businesses with net-zero goals should step forward so legislators receive a more balanced point of view on climate and clean energy laws. She noted that fossil fuels companies aiming to kill such legislation tend to dominate the dialogue and lobbying efforts.

The consumer products company has been a vocal proponent of climate and clean energy policies since it was founded in 1988, so aggressive advocacy doesn’t require special approval from leadership. Parent company Unilever is also known for making its voice heard on climate issues and for cutting ties with trade associations that don’t support its positions.

But the need for companies to advocate for climate regulations has become more urgent as global temperatures rise and federal leadership falters, Orgain said. Setting emissions reductions targets isn’t enough.

“We know we’re not going to be making a meaningful difference by our ingredients selection or packaging selection alone,” she said. “That will not get us to the pace and scale we need.”

Understand the superfund agenda

Climate superfund laws hold businesses accountable for the toll climate change takes on communities by assessing fees related to a company’s greenhouse gas emissions. New York’s law, for example, requires fossil fuels companies and heavy emitters to fund new infrastructure meant to protect the state from the effects of climate change.

Vermont’s law works in a similar way to cover the clean-up of climate related disasters, such as devastating floods that caused close to $500 million in damage claims in 2023.

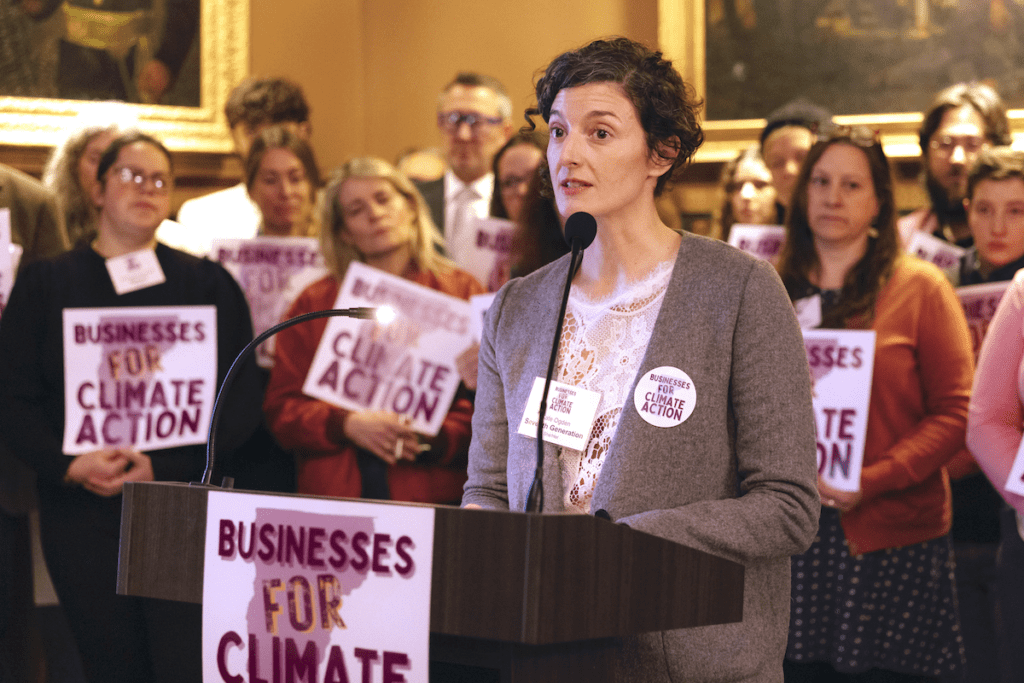

“This bill would ensure that the biggest historic polluters in the state — the companies that have known for almost 50 years that their products were destabilizing the planet we live on — that those companies pay their fair share of the costs inflicted on our state by the climate crisis,” said Seventh Generation’s Ogden at a February 2024 event organized to support the law.

The Vermont law was challenged as unconstitutional in December by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and faces resistance by the state’s Republican governor, who is emboldened by President Donald Trump’s agenda. Likewise, a group including 22 states and industry associations has sued to stop the New York version.

Team up with community-centered policy experts

Both Orgain and Ogden are actively involved with Vermont policy and politics, through relationships with the Vermont Businesses for Social Responsibility and Vermont Public Interest Group. That’s important for face-to-face and grassroots engagement.

“Building public support is super constructive, and having a company lobby for bills such as these goes a long way,” said Deborah McNamara, executive director of nonprofit ClimateVoice, which works with corporations on policy issues. “Companies are inherently involved with public policy, whether they like it or not. They are either obstructing consciously, keeping themselves on the sidelines or stepping out as leaders.”

Seventh Generation’s media budget for these sorts of activities is modest — much of its work is volunteer-driven — but when it does run ads it teams up with other companies and focuses on high-profile activities or comments suggested by organizers with lobbying expertise and strong community contacts.

“We are in a very small state that is leading on this work, and we answer the call when they ask us to show up,” Ogden said.

In New York, Seventh Generation became involved through NY Renews, a coalition of 380 environmental-justice and community groups. Getting businesses involved with the effort lent NY Renews more credibility, said Stephan Edel, executive director of the organization.

“Businesses are often siloed off, but being in tight communication makes everyone’s advocacy more effective,” Edel said. “The challenge becomes making sure that we are coordinated and aligned.”

Prepare a compelling offense — and defense

Seventh Generation views collective action as crucial in the fight to protect the New York and Vermont laws and to craft a unified message in support of new legislation. That’s one reason the company is building a business coalition to engage lawmakers on the new California legislation introduced in late February.

“Fossil fuels companies have a common narrative — pitting environmental concerns against affordability,” Ogden said. “It’s necessary for other businesses to fight against that message.”

In California, the burden of disasters on taxpayers — particularly wildfires — will fuel a firestorm of debate over SB 684 and AB 1243, dubbed the “Polluters Pay Climate Superfund Act of 2025.” Affordability is a conversation in every statehouse, Ogden said.

The bills’ sponsors point to a potential burden of $250 billion related to the January fires in Los Angeles as justification, underscoring the “financial injustices” of requiring California residents to pay for the damage. It also plays to health concerns. The legislation would charge oil and gas companies a fee proportional to their emissions in the state since 1990.

“We know we cannot make progress until we rein in the influence of the oil and gas industry,” Ogden said. “This is a way to have a huge impact on the climate without putting you head-to-head with the current presidential administration.”

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders