With a key alliance in limbo, banks are risking ‘zombie’ net-zero targets

The NZBA has frozen its activities, leaving the movement to shift to a low-carbon global economy in limbo, too. Read More

- The Net Zero Banking Alliance has paused operations after losing 20 members and facing ire from Washington.

- Despite net-zero pledges, banks continue financing oil, gas and coal.

- NGOs and investors, arguing that voluntary commitments have failed, push for enforceable rules to drive real decarbonization.

The demand is straightforward, if not simple: To slow climate change, stop funding fossil fuels now, not decades from now.

That’s what the International Energy Agency said in May 2021, only a month after 43 banks launched the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA). To some, the group’s formation, amid a flurry of related new alliances, offered hope that big banks were throwing their weight behind decarbonization in line with the Paris Agreement.

After all, the financial sector is arguably the root of all climate change. Businesses, which pollute at scale, can’t operate without institutional shareholders and financiers.

Yet four years and five months after its inception, the NZBA has frozen its activities and banks are keeping more fossil fuels in their portfolios than they did in each of the previous two years. Nevertheless, financial institutions continue to share their net zero-aligned intentions.

Where does this leave the movement to shift to a low-carbon global economy?

“What worries me is that I think there is a higher probability of zombie targets,” said Todd Cort, a senior lecturer in sustainability at the Yale School of Management. “They’re not living, because banks are not actively trying to push progress in the absence of outside pressure. But they’re not dead, because they still sit on the books. The downside is that we cannot afford to slow progress on climate. If there’s any upside, it’s that re-engaging with net zero will be easier if the target was never officially dismissed.”

The timeline

On Aug. 27, the United Nations-backed NZBA announced that it was pausing its operations, with members voting by the end of September on whether to become a guidance-only initiative. Whatever the result, critics argue that the NZBA had already slipped into irrelevance.

Twenty banks have fled the NZBA since December, kicked off by the U.S. “big six”: Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, Bank of America, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase.

In April, most remaining NZBA members voted to remove its Paris Agreement alignment. Only Triodos Bank left in protest over the thinned-out goals.

At the same time, however, all NZBA banks have kept their net zero targets. Just this week, Deutsche Bank issued its latest net zero transition plan. Even all of the exiting member banks, except Wells Fargo, appear to be maintaining net zero pledges, albeit with little in common. (That was partly the result of a March 2024 guideline favoring independent targets.)

Political pressures

Environmentalists have blasted banks for bowing to right-wing political pressure as they fled the NZBA.

In June 2024, for example, U.S. House Republicans railed against a “decarbonization collusion in ESG investing.” By the end of the year, Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, Citibank and Bank of America announced their NZBA exits.

In January, as President Donald Trump brought an anti-ESG rampage with his return to the White House, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton cited U.S. banks’ NZBA departures when he threatened them over their ESG commitments.

More recently, on July 22 the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) said that it would no longer validate the emissions targets of financial companies that fund new oil, gas or coal projects. On Aug. 8, an unusual letter followed by the attorneys general of 23 states, who charged the SBTi with violating antitrust laws.

However, there’s no consensus that political threats caused banks to change their minds about advancing climate plans, at least on paper.

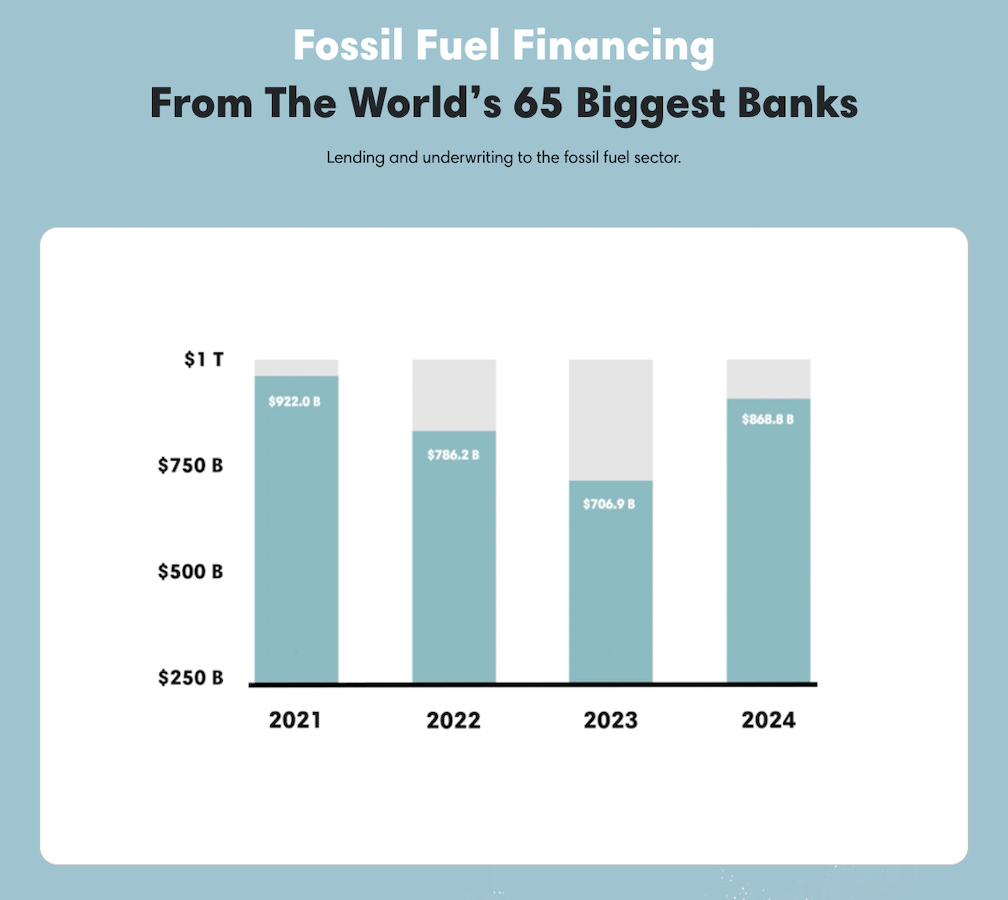

Fossil fuel financing by the 65 largest banks ticked upward to $868.8 billion after declining for two years following the NZBA’s formation, according to the Banking on Climate Chaos Report. The total was $922 billion in 2021, with a low of $706.9 billion in 2023.

Political cover for low ambitions?

“In our view, the political context in the U.S. was only a pretense that banks used to leave the NZBA,” said Quentin Aubineau, policy analyst on the banks and climate campaign at BankTrack, a Netherlands nonprofit that contributed to the “climate chaos” report. After all, the first banks to check out of the NZBA were also among the biggest fossil fuel financiers since 2021, he added.

“Banks want the best of both worlds,” said Abineau. “On one side, they want to be seen as climate leaders that are aligned with international climate goals. On the other side, they do not want to give up on short-term benefits and cut ties with their carbon-intensive clients, even if these clients are developing new fossil fuel projects that are incompatible with long-term climate goals.”

Barclays, the latest NZBA exile Aug. 1, boasted that it generated roughly $675 million “in revenues from sustainable and transition-related activity” in 2024. Yet it also invested $35 billion in fossil fuels, a four-year high.

For Saskia Straub, climate policy analyst at the New Climate Institute of Cologne, Germany, political headwinds catalyzed NZBA departures but also exposed the low integrity of many bank targets. They have been “plagued by loopholes,” she said.

“This raises questions about whether the initial commitments were driven more by a desire to follow trends and manage public relations than by a genuine intent to decarbonize,” Straub added.

What should banks do?

“Our research suggests that instead of focusing on long-term targets, financial institutions can have an impact by dedicating their resources to engaging their investees and directing finance to achieve real-world decarbonization in the short term,” Straub said, citing her organization’s Aug. 26 report, “Fixing the Broken Governance Chain.”

It encourages banks to set consequences for their funding recipients’ high-emissions actions. Banks can also channel capital into activities that support a low-carbon economy, Straub added.

NGOs including BankTrack, ShareAction and the Sierra Club call for regulators to step in to cement climate progress where optional collaborations are failing.

“Voluntary commitment frameworks like NZBA can be effective, but they only work if backed by enforceable rules,” said Sierra Club Sustainable Finance Campaign Adviser Jessye Waxman.

Most of all, banks need to own their culpability for fueling emissions, whether by directly financing fossil fuel projects or by including oil, gas and coal in their investment portfolios, according to Aubineau.

Investor pressures

Beyond threats by politicians, activists have mounted hundreds of protests against banks propping up fossil fuels over the past year. Wells Fargo, the only NZBA bank to ditch its net zero pretenses entirely, has taken much of the ire in multiple U.S. cities this summer.

From London, Louise Marfany, director of financial sector standards at NGO ShareAction, warned that many investors will not tolerate backsliding from banks on their commitments to reduce their financing of high-emitting activities.

Case in point: PFZW, one of Europe’s largest pension funds, said Sept. 3 that it was yanking nearly $7 billion in holdings from BlackRock due to its lack of support for climate action.

“Banks that attempt to roll back on the vital commitments they have made to safeguard people and planet should expect significant pushback,” Marfany said.

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders