Amazon’s plan to restore 1.85 billion gallons of water highlights AI’s soaring demand for water

A vast majority of data centers use water to keep servers and networking gear from overheating. Read More

Amazon Web Services is funding six new water replenishment projects in watersheds stressed by climate change, population growth and economic activity.

The investments in Brazil, China, Chile and the U.S., along with 15 existing initiatives, will return an estimated 1.85 billion gallons of water annually when they’re instituted. That’s roughly double the amount of water restored by Amazon-funded efforts in 2023, according to an Aug. 27 blog.

In 2022, Amazon Web Services (AWS) announced a plan to become “water positive” by 2030 by returning “more water to communities and the environment than its direct operations use.”

It selects projects such as pipe leak detection programs, irrigation technology investments and ecosystem restoration to offset projected water demand as its data center portfolio grows, largely driven by customer demand for artificial intelligence-enabled applications.

“We know at least a few years out where we are heading,” said Will Hewes, global lead for water sustainability at AWS. “All these decisions are interrelated.”

Data centers are thirsty

A vast majority of data centers use water in on-site equipment to keep servers and networking gear from overheating. AWS operates more than 100 data centers worldwide, 24 of those without using potable water, relying instead on other methods including the use of recycled water, according to Hewes. Alternatives such as liquid cooling systems are emerging.

One 2021 study suggests that 20 percent of U.S. data centers are in regions at risk of water shortages. Artificial intelligence is increasing that stress, and could account for 4.2 billion to 6.6 billion cubic meters of water withdrawal by 2027, according to October 2023 research from the University of California, Riverside and the University of Texas at Arlington.

CSRD Made Easy: From Compliance to Opportunity with AI-Enabled Sustainability Solutions

That figure includes water used on site by operators and for power generation by utilities. “Electricity use and water use go hand in hand,” said Alex de Vries, researcher at De Nederlandsche Bank and founder of Digiconomist, a research firm that studies the environmental impacts of digital infrastructure.

A growing number of communities and U.S. states are greeting proposals for new data centers with skepticism or hostility because of anticipated water, energy and land use considerations, he said. Georgia, South Carolina and Virginia lawmakers have all introduced legislation that could limit data center development, due to concerns about energy and water use.

Water stewardship looms large for Big Tech

AWS, Google and Microsoft are all investing in water restoration and sanitation projects near new data centers as their water use grows. They’re in the minority. Most data center companies don’t disclose much about their water consumption, said David Sedlak, professor of environmental engineering at the University of California, Berkeley.

Heightened public scrutiny of the environmental impact of AI, especially its growing appetite for electricity, has more customers and consumers asking about the consequences for water. There are close to 80 data centers in Phoenix, a city struggling with water access and quality issues, and Google is planning another one.

Water replenishment is becoming similar to carbon offest programs, said Sedlak; growing demand for energy and for water is driving new attention and new investment from large corporations.

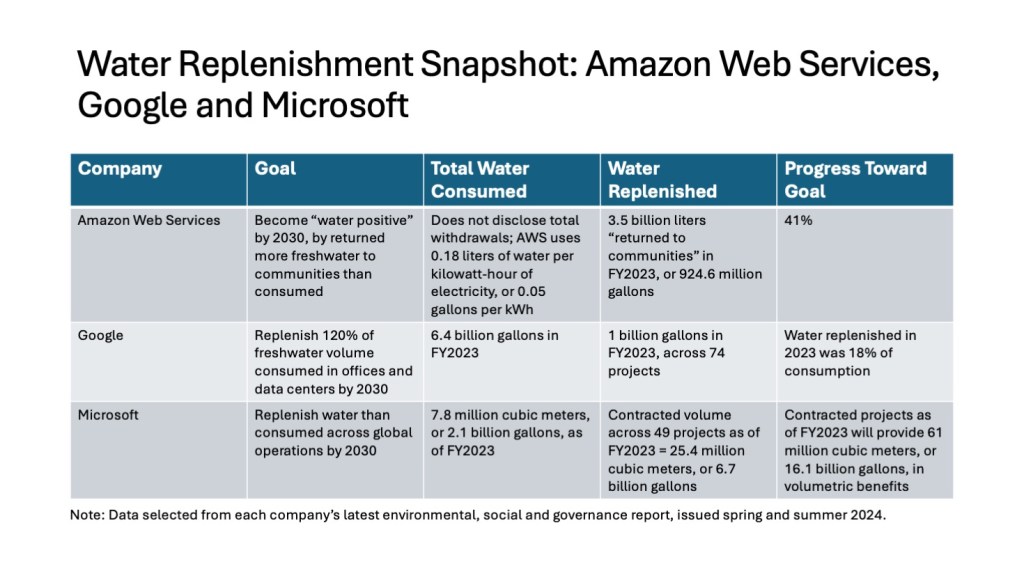

The table below outlines goals and progress disclosed by AWS, Google and Microsoft.

A rarely disclosed metric: Water usage effectiveness

AWS was 41 percent of the way toward its water goal as of December, according to the company’s 2023 environmental report.

Unlike Google and Microsoft, AWS doesn’t disclose how much it withdraws annually. It shares a different metric, water use effectiveness (WUE), which measures the amount of water used per kilowatt-hour of data center operations. It’s calculated by dividing a data center’s annual water consumption by the amount of electricity used by the IT equipment. In 2023, that number was 0.05 gallons per kWh. The industry average is 0.5 G/kWh.

“Withdrawals are important, but consumption is what really matters,” de Vries said.

Best practices

AWS put measures in place before beginning its replenishment program. More details can be found in this new water stewardship playbook:

- Map risks and potential impacts, using databases such as the World Resource Institute’s Aqueduct database.

- Choose metrics for water accounting, such as water withdrawn, water consumed (which calculates withdrawals minus discharges) or water intensity metrics such as the amount of water consumed per product shipped. From there, conduct an audit.

- Calculate water used outside of direct operations, such as what’s consumed for power generation or what’s used by customers in the use of a company’s products.

- Invest in efficiency measures to reduce operational consumption, such as faucet aerators, water meters and native vegetation, or to cut freshwater withdrawals, such as rainwater harvesting or recycling systems.

“It’s a good idea to exhaust ‘inside the fence’ operational efficiency measures before pursuing replenishments,” AWS said.

Each of the 21 projects across the AWS water portfolio is unique to the watersheds it serves. Its first initiative in Chile, for example, will use drip irrigation technology from startup Kilimo to save about 52.8 million gallons annually in the Maipo Basin, the largest source of water for Santiago and Valparaiso. At its first project in China, AWS will support reconstruction of wetlands at a reservoir near Beijing to naturally treat agricultural runoff.

Engagement with local partners to define efforts that best serve communities is “one of the through lines and uniting themes across a diverse set of projects,” said Hewes.