Companies attract investors with strong water governance policies

Investors are zeroing in on how companies like Molson, Coca-Cola and Diageo tackle water risks, and increasingly they’re focusing on the boardroom. Read More

Among global food companies, there is a so-called drought of water-aware boards of directors. And for an industry that uses 70 percent of the world’s fresh water, on a warming planet with scarcer resources, that lack of awareness is a concern.

Investors are zeroing in on how companies are tackling water and sustainability risks, and increasingly they’re focusing on the boardroom. In a recent Ernst & Young survey of some 320 investors, more than 75 percent said that mandatory board oversight of sustainability disclosures is “essential” or “very useful” when making decisions about whether or not to invest in a company.

Little wonder. Companies that have strong board oversight on sustainability issues, including water, send a signal to investors that they’re serious about these issues. And experts have long asserted that businesses perform better on actual indicators of sustainability when their boards are engaged.

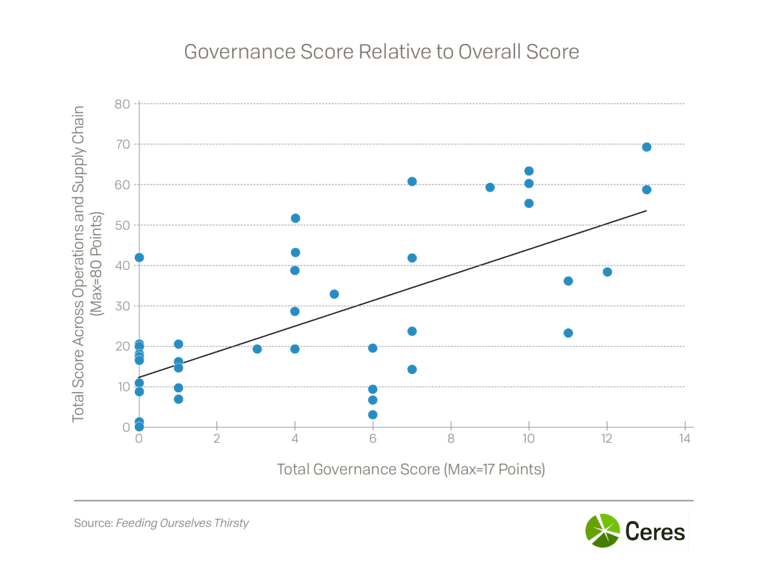

Now Ceres has research to back up the strength of this connection.

In the recent update of our “Feeding Ourselves Thirsty” analysis, we found that among the 42 major food and beverage companies that we benchmarked on water risk management, there was a strong link between stronger governance and companies that performed well across the other categories, including operations and supply chain.

Campbell Soup Company, for example, is among a small but growing group of companies that increasingly recognize the importance of strong governance when it comes to sustainability. It’s one of four companies, along with Coca-Cola, Diageo and Nestlé, that briefs its board on water-related issues. All four scored among the top 10 in our benchmarking analysis.

“Campbell’s CEO and board appreciate the opportunity to understand and assess sustainability performance within the context of core business strategy,” Dave Stangis, Chief Sustainability Officer at Campbell Soup Company told me. “Building that into the governance process drives accountability within the enterprise.”

Or consider Molson, the third-highest ranking beverage company in our analysis. As a part of the board’s mandate to oversee executive compensation metrics, Molson’s board has identified sustainability as a key indicator to measure executive performance. At Molson, the corporate executive team is rewarded based on a set of metrics measured against the company’s 2020 sustainability targets, including water use.

Unfortunately, these companies are the exception rather than the rule. Not enough corporate boards are stepping up. Overall, the food companies we analyzed managed on average to get just 4.5 points out of the 17 we awarded on governance. And a string of major players scored a perfect zero — including Cargill, Archer Daniels Midland, Chiquita Brands and Tyson Foods.

The takeaway is clear. On key indicators, ranging from board oversight of water-related issues and links between executive compensation and sustainability goals, the industry is lagging when it comes to governance.

For instance, half of the boards we analyzed did not oversee material risks and opportunities related to sustainability and water. And even though we saw an increase in companies starting to link executive compensation to the management of water-related issues, 71 percent of businesses didn’t take this critical step.

Companies simply cannot afford to keep ignoring water and other sustainability issues like climate change that could materially affect corporate financial performance.

For the $5 billion food sector, the combination of climate change and growing threats to water scarcity, including population growth and pollution, is turning water into one of the sector’s biggest financial risks. In 2016, multinational corporations disclosed that they faced $14 billion of water-related risks, a five-fold increase over the previous year.

Boards have a fiduciary responsibility to act when risks are material. And that is why more companies need to develop sustainability competent boards.

By understanding what climate change or water stress means, why it matters to their business and what their organizations can do, directors can successfully make climate and water risk part of their governance systems.

That way, boards will be able to respond to the rising scrutiny among investors. They’ll be able to help prepare their companies for the risks and the opportunities created by water stress, climate change, or forced labor in their supply chains.

“Lead from the Top” outlines three basic steps companies can take to have a sustainably competent board: integrate knowledge of material sustainability issues into the board nominating process to recruit directors that ask the right questions; educate all directors on material sustainability issues to allow for thoughtful deliberation and strategic decision-making at the board level; and engage regularly with external stakeholders and experts on relevant sustainability issues.

Again and again, we’ve seen how strong governance — or lack of it — determines whether companies thrive or stumble when they have to deal with major market challenges. The corruption, deforestation and tainted meat scandals engulfing JBS, the world’s largest meat producer, drive home the importance of good leadership in tackling key challenges and maintaining profitability in the long-term.

Food companies need to better prepare for the huge threat that water risks will have on their business. Turning that around will depend in large part on whether boards start waking up to the financial risks that water poses to their business.