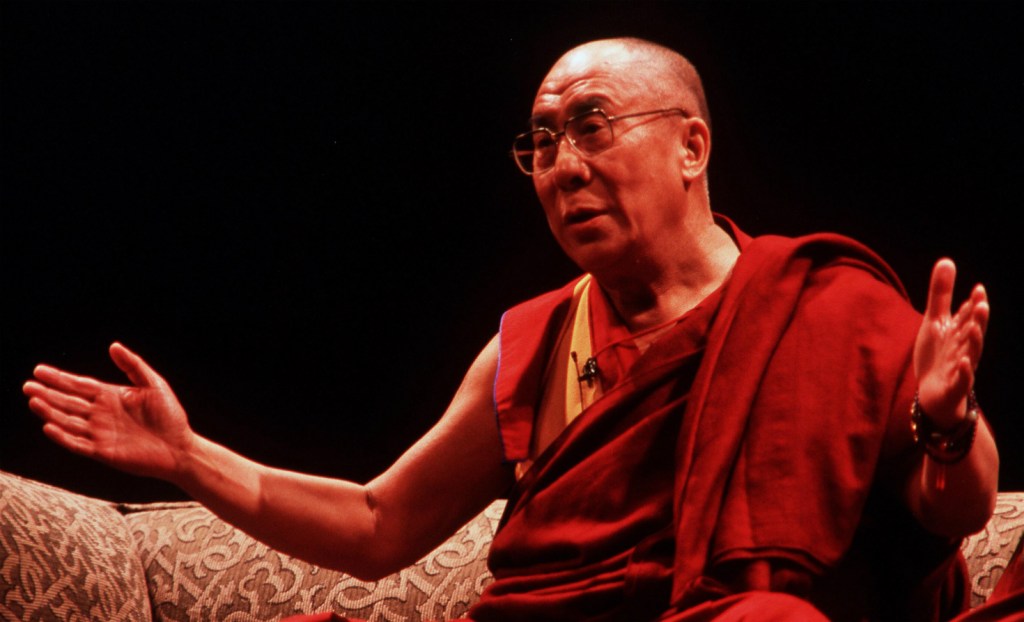

The Dalai Lama on the responsibility of business

Many corporations have failed in recent years. What can start leaders on a better path for the future? Read More

Sander Tideman began his professional life as a lawyer and banker. Over time, he found himself increasingly questioning the underlying motivations and goals of businesses leadership and began seeking a new paradigm for a more sustainable approach.

Sander’s search for an alternative was inspired by a chance meeting that he had as a young man with the Dalai Lama. Over the following years, his friendship with the Dalai Lama grew and prompted Sander to organize a series of dialogues between the Dalai Lama and leaders in business, education, government, economics, science and health; these conversations have explored the ways in which business leaders can serve as a wider force for good and bring about positive change in the world.

This extract from his book “Business as an Instrument for Societal Change: In Conversation with the Dalai Lama,” published by Greenleaf Publishing, examines some of the critical issues facing business leaders today.

Bill George (Professor, Harvard Business School): I want to shift the conversation to a subject that has been my passion for a long time. As you are well aware, in recent years many corporations have failed. In the process, so much economic value and so many jobs and lives have been destroyed that our media has branded the leaders of these failed companies as bad leaders.

However, in studying them closely myself, I’ve come to the conclusion that these people didn’t set out to do evil things. Most lost their way en route to the top by seeking external gratification — money, power, titles, status and prestige. What the leaders of many failed corporations never developed in all that rush toward success was what you might call an inner life — they failed to cultivate their hearts.

As a result of this, one of the things we’re trying to do with talented young leaders today is to start them early on a path where they understand that their lifelong development as leaders is parallel to the development of their inner life and the cultivation of their hearts. If you agree with this premise, what would you tell young leaders to do today to prepare themselves for their significant future leadership responsibilities?

As a result of this, one of the things we’re trying to do with talented young leaders today is to start them early on a path where they understand that their lifelong development as leaders is parallel to the development of their inner life and the cultivation of their hearts. If you agree with this premise, what would you tell young leaders to do today to prepare themselves for their significant future leadership responsibilities?

The Dalai Lama: My view is that it is not simply a moral issue. I believe, whether it’s in the economy, or politics, or education, we need to carry out all human activities with human feeling, because everything in reality is interconnected. All the books young leaders read about politics, economy, religion, education and so on — even if they address specific topics — are all meant for humanity as a whole.

Taking the holistic view, even in your specific field of business and the economy, is best. Economics means dealing with humanity, and the situation of humanity changes century by century, year by year. Once they understand that reality is constantly changing and that everything is interconnected, leaders begin to realize that they have to keep the consequences of all their actions always in mind.

Although a leader may get some immediate economic profit in a particular case, there may be other important side-effects that weren’t considered. The broad-minded perspective and the more holistic view, which can see reality in its totality and understand the longer-term effects, is essential for leaders today.

For example, I’m a religious person, a religious practitioner. I am a Buddhist but I also respond to non-Buddhist and nonreligious people who ask me for teachings and explanations. When I am explaining something, I try to keep in my mind if my main audience is Buddhist or not, religious or not, and then I adjust my teachings accordingly. If I only look at my Buddhist interests, I may actually be in conflict with my other aim of promoting religious harmony.

So, although I’m engaged in explaining Buddhism to certain people, at the same time I have to keep in my mind the implications for other, non-Buddhist people. If you just think about your own religion and nothing else, then — although your motivation may be sincere — there could be some undesired consequences.

I know that some religious people, Christians for instance, speak about their religion very sincerely and with great enthusiasm, but if they only speak from their own specific religious perspective there can be negative consequences. So, that is my view with regard to business leaders as well. Reality is so complex, so interconnected; we all need a very broad perspective.

Peter Miscovich (Managing Director, JLL): I work for a large consulting organization and we help organizations transform themselves so that they become better workplaces, perform better and create more value. My question is: how do we expand and have these new concepts of holistic thinking, long-term views and compassionate motivation embedded into global organizations? What do you recommend in terms of organizational transformation to help people embrace these new concepts?

The Dalai Lama: Would any of the panelists like to respond to that?

Barbara Krumsiek (Member of Board of Directors, Pepco Holdings): I would just quickly say that I think there are two elements to transformation. There’s the leadership and then there is every person in the organization. I don’t think transformation is possible without both of those elements being in alignment. Leaders have to be able to set the tone and be able to inspire every individual — in some senses, everyone has to buy into the transformation. I think the harsh reality may be, as His Holiness has said, that if some people will not buy into the transformation, then maybe they don’t belong in the organization.

Bill George: I agree with that, Barbara. I think organizational transformation has to be throughout an organization. You can’t take a factory within a company or a division within a corporation and transform it. The key is a common mission, people coming together around a common sense of purpose. And it can’t just be a set of words. It has to have real meaning that’s felt deep inside, and a common set of values so that people can develop trust.

And then it has to be tested in the crucible. It has to go through the refiner’s fire. In other words, it has to be upheld even in difficult times and when things are not going well. And if the organization stays true to its purpose and its values in that difficult time, for example, when the market share is going down, the organization is losing business, the economy is bad, and some key people quit, that will be the test.

And, if the leadership then goes in a different direction, and says, “Oh, now we can’t stay true to our purpose and values, we have to do this because things are tough,” then the transformation will be lost forever. You are better off not to start the transformation in the first place.

So, the leadership has to be fully committed, knowing they will be there when times are difficult; because if they’re not, then there will be just a sense of cynicism across the organization. So many leaders try to start these efforts because they think it is a good thing to do, but they haven’t really thought through the whole process and aren’t prepared to stay committed through difficult times.

Finally, I think we have to recognize that leadership in a transforming organization must exist at all levels. People on the production line, people serving the customers, people in the finance department, everyone has to lead and the leader has to be out with the people. If the leader is in Wall Street at security analyst conferences, it will all fall apart.

And then, the organization needs to say very clearly what it stands for to the outside world so that it will have a buffer — an understanding on the part of people, as Barbara Krumsiek says: “This is what we stand for. And if we go through difficult times, we’re asking you to stay with us because we’ve stayed true to our mission and our values.” So, that’s the only way you can have long-term transformation.

It takes about five years. If you’re interested in a six-month transformation, forget it. You’re just trying to impress the stock market and it won’t work. It takes five years because you have to go through difficult times before people believe you. So, if you’re serious about it, as for example IBM has been very serious about it, it’s going to take at least five years, and in their case, 10.

And that’s why so many organizations who have attempted have failed so many times because they aren’t really serious about it. It has to be a transformation committed to and with people. It can’t just be an external transformation, the mission statement on the wall. It has to be something that goes on inside people so there’s a belief there.

And that’s a transformation of consciousness. And if there’s not that transformation, then it can’t work. People have to believe that their leadership really cares about this coming together around a common purpose, a set of beliefs and a set of values.