In the wake of devastating fires, California architects and developers turn to natural materials

Adobe, rammed earth and hempcrete are more fire-resistant and less damaging to the climate than conventional materials. Read More

As Southern California recovers and rebuilds after January’s devastating fires, a thriving ecosystem of architects, engineers, builders and entrepreneurs is working to move natural building materials into mainstream construction.

Homes built with straw bale, adobe, hemp and other natural materials show better fire resistance than traditionally built homes, which are increasingly built using flammable plastics. Bio-based construction materials are generally healthier for inhabitants, because they contain fewer toxic chemicals and have smaller carbon footprints.

Already, in communities ravaged by the Palisades Fire, residents are circulating petitions calling on government officials to rebuild using natural building technologies, and Los Angeles County Supervisor Kathryn Barger expressed a willingness to consider them at a community meeting.

“Agricultural residues make really good building products,” said Chris Magwood, manager of carbon-free buildings at Rocky Mountain Institute. “When you look at all the criteria — good in fire, low in embodied carbon, low in toxicity — they really shine.”

The straw solution

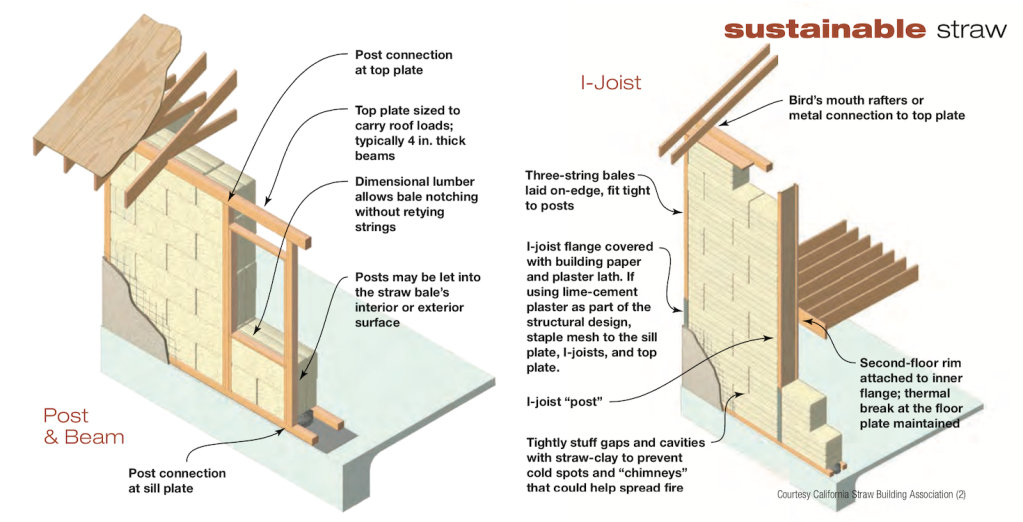

Traditional straw bale construction, which has been employed for more than a century and has grown in popularity since the 1990s, uses densely packed agricultural byproducts, such as stalks from wheat, supported within a wooden frame that is plastered to form interior and exterior walls. Currently, it is more commonly used to insulate buildings in Europe and Australia than in the U.S.

Straw bales can be used in a variety of construction formats, including drop-in solutions that use straw insulation. Credit: California Straw Building Association

Although thinking of straw as a fire-resistant material may seem counterintuitive, Drew Hubbell, principal of Hubbell & Hubbell Architects in San Diego, likens bales to phone books. In a fire, “the edges fray but you can’t burn the inside,” Hubbell said.

In fact, fire testing shows that a plastered bale wall can endure a simulated house fire for two hours before it starts to burn. That’s double the fire resistance of traditional wood framing with fiberglass insulation, according to Hubbell.

Hubbell pioneered straw bale construction in Southern California, using rice, wheat and barley stalks produced by Imperial Valley growers, and has built some 50 straw bale homes over the last 20 years.

Farther north, Berkeley architect David Arkin has built dozens of straw bale structures over the past 20 years, including a 34,000-square foot warehouse office building, a nature center in Sierra Valley and a four-unit townhome project in Oregon that achieved an 85 percent reduction in embodied carbon.

A principal at Arkin Tilt Architects, Arkin founded the California Straw Bale Association and worked with others to get the method into the state’s building codes. As a member of the Bio-Based Materials Collective, he’s working on an Environmental Product Declaration for straw bale to help market the material to a wider audience.

“If we’re going to continue doing anything on this planet as human beings, it’s build shelter to meet our needs, and if we can build that shelter with carbon storing materials, then buildings can become the Earth’s fixed carbon sink,” Arkin said.

Drop-in products are the path to greater scale

Structures built by Arkin and Hubbell use bales straight off the farm in a thick wall system, which adds surface area and costs and isn’t practical in dense urban areas.

It’s also harder for builders than conventional materials, Arkin said. “Architects write specifications for builders and when it comes to straw bale construction, your specification might read … ‘Find a local farmer who’s harvesting bales that are clean, dry and densely packed.’ And at that point, there’s smoke curling out of their ears.”

Such barriers led Anthony Dente, a principal at Verdant Structural Engineering, to develop a drop-in building insulation product made from straw bales. The product is a prefabricated structural wall panel that builders can easily work with in conventional structures.

Although his firm has worked on some 300 natural building projects around the country, he said, with the thick wall systems, “I just realized we were never going to scale.”

Dente’s startup, Verdant Panel, is fundraising a seed round to expand its manufacturing capacity and refine its insulation efficiency, to make it equal to or better than fiberglass or rockwool. The product is already compliant with building codes.

“If we can bring this material — which blows alternatives out of the water with embodied carbon — to scale with equivalent performance and cost as conventional insulation, it becomes the obvious choice for future construction,” Dente said.

Other natural builders

New Frameworks in Vermont, Europe’s EcoCocone, which sells in the U.S., Texas-based Agriboard and Oklahoma-based Western Fiber are other companies with straw bale insulation building products.

“Products and systems that can be specified… are [straw bale’s] path to greater scale, both in volume and in bigger buildings,” Arkin said.

Supply isn’t a limiting factor. Magwood said his research shows that enough wheat straw — the stalks left behind after the seeds are harvested for flour — is produced in the U.S. to build a million homes a year, and that’s just one agricultural byproduct with construction potential.

Adobe and rammed earth

Traditional adobe construction, in use for centuries, has a fire resistance rating of four hours but is more time-consuming to build than straw bale and has higher labor costs.

Hubbell has built structures from adobe and rammed earth — which is similar to adobe, but comprise an earth and cement mixture over a plywood frame, rather than bricks. (In California, rebar is also required.) Rammed earth structures have been built at Napa Valley wineries including Long Meadow Ranch and Meteor Vineyard.

But “the whole [adobe] ecosystem isn’t mature enough to scale much beyond 50 homes a year” in Southern California, said Los Angeles architect Ben Loescher, a principal at Loescher and Meachem Architects, said.

Building codes present another barrier. Adobe is currently an “orphaned section” in California’s building code that hasn’t been updated or coordinated with other parts of the building code, Loescher said.

Loescher is championing efforts to change California’s building codes through Adobe is Not Software.

Hempcrete: the new kid

A handful of U.S. companies, including Americhanvre, Hempitechture and HempStone, produce a material called hempcrete or hemp lime, a composite of hemp hurd, the part of the plant that remains after the higher value fiber is removed, and a lime-based mineral coating.

Hempcrete spray insulation has achieved at least a one-hour fire rating test.

Like adobe, hemp construction is not yet incorporated into California’s building code. Supply has also been challenging “because it’s a relatively new industry and it’s been illegal for a long time,” Loescher said.

Amanda Martin, owner of the Ventura County construction company Renewal Revolution, was inspired to build with natural building materials after the Thomas Fire ravaged her community in 2017, consuming more than 1,000 structures and burning 283,000 acres.

Martin is a member of the U.S. Green Building Council’s board and regional lead for the U.S. Hemp Building Association. She has consulted on six or seven hemp homes, and built a 720-foot accessory dwelling unit, or ADU, in Calexico that has already withstood a fire.

“I am open to building any way that someone wants to build that is regenerative,” she said, but “I’m sticking my neck out with hemp, because it’s an amazing solution that is more versatile than other green building products.”

Hemp, adobe and straw bale are still on the fringes of construction for now. But more frequent and more destructive fires are likely to change that.

“I think it’s fair to say that $60 billion in property damage, 50 lost lives and devastation in two Los Angeles neighborhoods is sufficient reason to go back, look hard at the way things have been done, and consider building materials that are inexpensive, inherently fire resistant and low carbon,” Loescher said.

[Join over 1,500 professionals transforming how we make, sell, and circulate products at Circularity, April 29-May 1, Denver.]