For investors, U.S. super-regional banks are a critical blind spot in climate risk disclosure

A new report underscores how much super-regional banks are lagging on climate action — particularly risk disclosure — while facing less scrutiny than the largest financial institutions. Read More

The low-carbon transition is reshaping every sector of the economy — but a key part of the banking industry isn’t getting enough attention from investors.

Super-regional banks — the large financial institutions that do business in many states across the country and in some cases have similar assets and revenue as the Big Six banks — also face the same climate-related risks as these global giants. But they face far less public accountability.

The result? Investors lack the information they need to fully understand their portfolios’ exposure to climate risk.

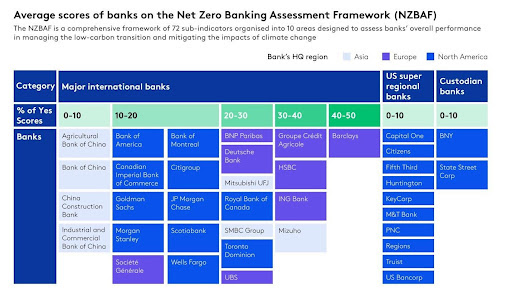

This week, a report from the Transition Pathway Initiative Centre at London School of Economics sheds new light on how major international banks and, for the first time, 10 U.S. super-regional banks, are stacking up on climate action.

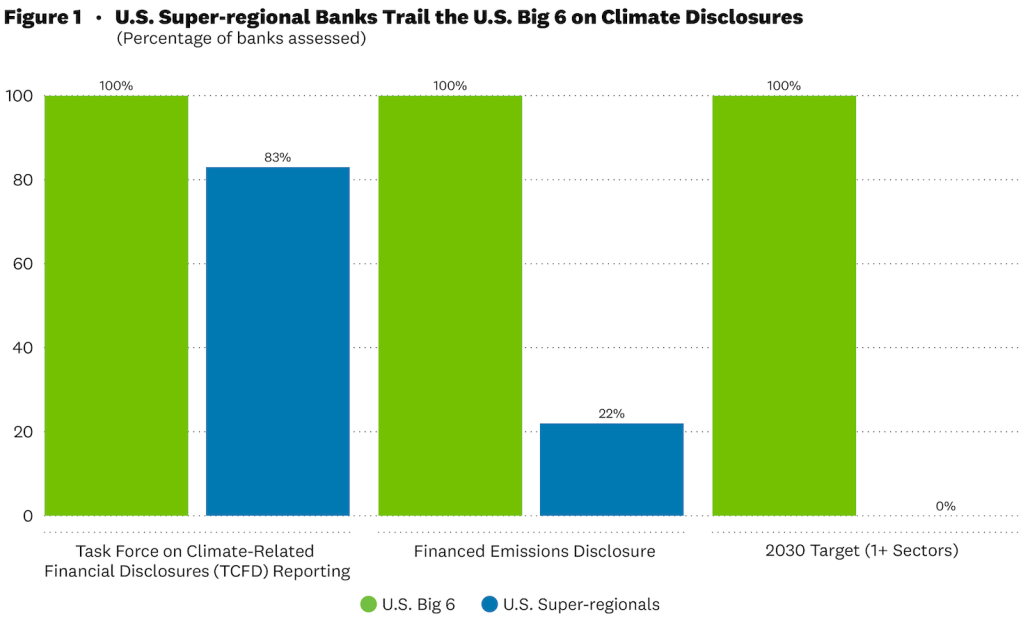

The findings underscore just how much the super-regional banks are lagging on climate action — particularly when it comes to climate risk disclosure. U.S. super-regional banks’ scores were even on par with major Chinese banks, notorious for their weak climate performance. According to the analysis, the lack of comprehensive public data from these super-regional banks is hindering a meaningful evaluation of their climate practices.

For investors, this should signal the need for deeper engagement with super-regionals, pushing them for detailed public disclosure of their energy financing.

The risks of little insight

Through their engagement with the six largest U.S. banks, investors are making strides, driving them to commit to reducing their fossil fuel lending and increase transparent reporting.

The logic behind this engagement is clear: Banks play a central role in financing the industries driving global emissions, so they are uniquely exposed to legal, reputational and financial risks from climate change. Banks that address these climate risks and capitalize on profitable opportunities in clean energy strengthen their resilience in a rapidly changing market. And investors with net-zero targets, now representing most top U.S. asset managers, inherit the material financial implications — both risks and opportunities — as shareholders of these financial institutions.

But so far, the scrutiny around climate risk exposure and action has mainly focused on only the largest global financial institutions, leaving super-regional banks largely ignored — despite their potential impact on the economy.

Consider the fallout from the 2023 collapse of only three banks — First Republic, Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank. Super-regional banks such as Truist and U.S. Bancorp have four to six times the assets of Signature Bank, and are almost as large as Morgan Stanley, one of the Big Six banks.

This should concern investors because some U.S. super-regional banks rank among the world’s top financiers of fossil fuels, and a few even top the list when looking at fossil fuel financing as a percentage of their total assets, according to a 2024 report by Rainforest Action Network.

Increased financing of fossil fuel industry

What’s more troubling is that while the Big Six U.S. banks have made net zero commitments and set medium-term targets to slow their fossil fuel lending, there is growing evidence that super-regional banks are stepping in to fill the gap.

BOK Financial — a super-regional based in Tulsa, Oklahoma — recently said banks like theirs are “active and hungry” for new oil, gas and coal projects. As the fossil fuel industry looks for new sources of capital, some super-regional banks are poised to expand their lending, further entrenching their financial risk.

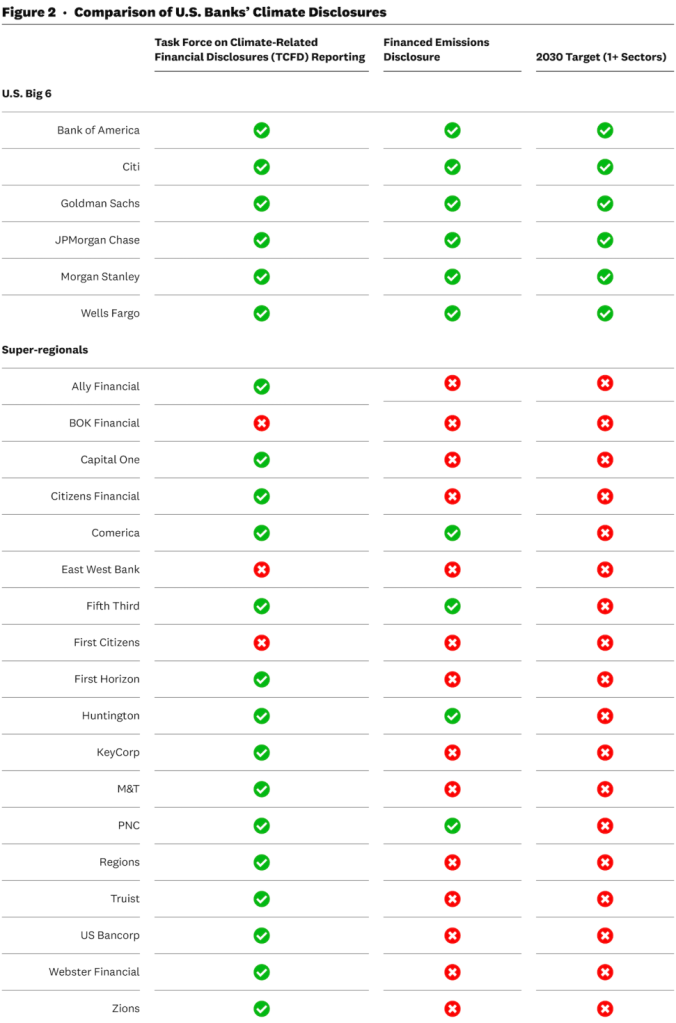

And while most are committed to some climate disclosure, few super-regional banks disclose their fossil fuel lending. These financed emissions — the carbon emissions of the companies they lend to — are what really matter to investors. Studies by CDP have shown that for financial institutions, financed emissions can account for over 700 times their operational emissions.

There has been some progress, however. A few U.S. super-regional banks are taking steps to address and disclose their climate risk. TPI’s report found that U.S. Bank has set net-zero targets inclusive of financed emissions, and a few banks have begun to disclose these emissions.

Again, part of the reason for these positive steps is bank responsiveness to investor engagement, particularly during the proxy season, with shareholder requests driving an increase in disclosure. Investors filed nine climate-related resolutions at U.S. super-regional banks between 2022 and 2024 requesting they adopt greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets and report on their climate-related lobbying and operational climate impacts. Five were withdrawn for commitment and one received management’s support when it went to a vote, indicating that U.S. super-regional banks are generally responsive when investors engage them on climate issues.

The takeaway for investors? Without better climate disclosures from super-regional banks, investors cannot make informed decisions about the long-term resilience of their holdings. If these banks continue to fly under the radar, their exposure represents a massive blind spot in climate risk management and investment opportunity.