H&M and other brands have had their fill of down

Animal welfare activists hope down will become taboo, like fur. Brands are using recycled, synthetic and plant-based fill, but the down industry defends its climate-smart credentials. Read More

Animal rights activists scored a win Oct. 4, when H&M announced its phaseout of virgin down feathers in all products by the end of 2025. Instead, the fashion brand will stuff puffy coats and bedding with post-consumer recycled feathers and synthetic materials.

Ninety percent of H&M’s down is already recycled from comforters, pillows and jackets unwanted by consumers. It is certified to the independent Recycled Claim Standard (RCS) or Global Recycled Standard (GRS).

As fashion brands shift away from down feathers, animal rights activists hope down will follow the path of fur and become obsolete. More are exploring recycled, synthetic and plant-based alternatives, but the down industry defends its climate and humane credentials.

But synthetic alternatives to down come with their own set of controversies that is leaving fashion brands walking a tightrope between activists, consumers and shareholders.

Down has endured for at least 800 years. A poem from the Tang Dynasty mentions a feather duvet. Outdoorsman Eddie Bauer popularized down jackets for skiers in the 1950s after a hypothermic fishing trip. Product reviewers praise down’s heat-retention superiority. But could feather down become taboo, like fur?

H&M’s move follows a PETA-led campaign, involving picketing of retail stores and 150,000 consumer letters, demanding the company to cease the use of down. The 6.5-million member Norfolk, Virginia, watchdog owns one share of H&M stock so it can engage in shareholder activism.

“It’s pretty clear H&M’s action proves, once and for all, that there’s no reason for companies to continue paying to kill birds for puffers or pillows or anything else when there are so many wonderful alternatives available,” said Jacqueline Sadashige, manager of corporate responsibility at People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.

In 2021, H&M and PETA partnered on a limited edition vegan collection called the Co-exist Story. It featured flower-based “down” filled puffer jackets and grape skin-based pleather pants.

PETA claims credit for influencing Ascena Retail Group, owner of Ann Taylor, Loft and Lane Bryant for discontinuing down in 2023. The group has also pushed Lululemon, Marks & Spencer and Lacoste to forgo the feathers.

Brands such as Save the Duck, Prana, Noize and bedding maker Buffy have built identities around exclusively using vegan synthetics.

The humane and climate cases against down

“It really is a movement as people become more and more aware of the cruelty and suffering that’s involved in down products,” Sadashige said.

Goose and duck down feathers are a byproduct of the meat industry, which contributes to 14.5 percent of annual greenhouse gas emissions, according to the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). Poultry makes up just 8 percent of the livestock sector’s emissions.

PETA considers vegan alternatives, sourced from plants or fossil fuels, to be the only ethical options. The practice of force-feeding ducks for foie gras is just one PETA complaint. Its numerous “exposé” videos show geese live-plucked by hand and flapping, upside down on a slaughtering assembly line in Poland, the fourth largest down exporter after China, Taiwan and Germany. Some of these companies are purportedly certified by the Responsible Down Standard (RDS), which is supposed to ensure humane treatment.

Animal cruelty, environmental degradation and harm to humans go hand in hand, according to Sadashige. After all, the H5N1 bird flu originated in a commercial goose farm in 1996, she noted.

Doubling down on down

The down industry maintains that it follows humane practices.

“Over 90 percent of the value of a bird is the meat so it makes no sense” to live-pluck a bird, which ruins the meat, according to the nonprofit Downmark of Canada. Typically, high-speed machines pluck feathers off dead birds, adds the organization, a member of the International Down and Feather Bureau (IDFB).

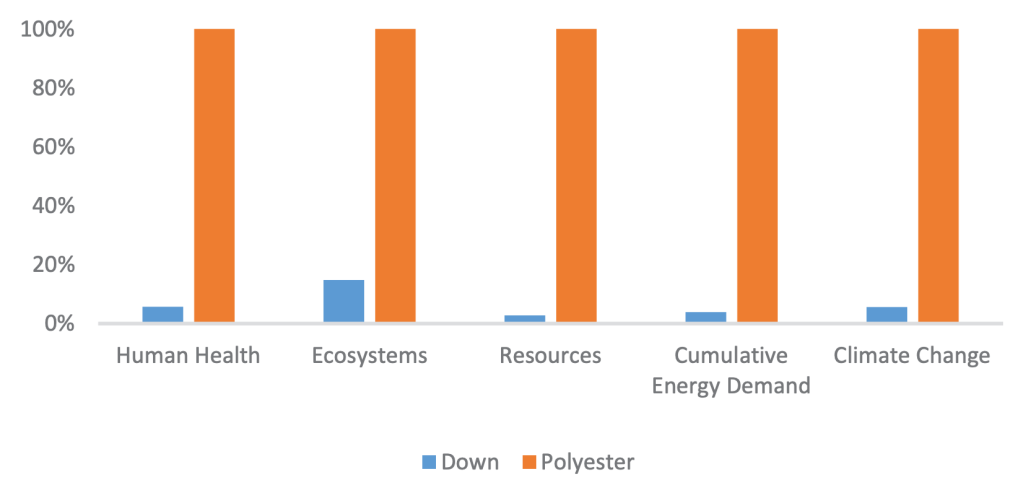

Proponents of down argue that it’s a renewable resource, a circular byproduct of meat production, and generally more sustainable than petrochemical fibers. From a third-party lifecycle assessment, the Lustenau, Austria-based IDFB determined that down offers:

- A 92 percent lower CO2 equivalent emissions than polyester.

- An 85 percent lower impact than polyester on land and marine ecosystems.

- 18 times less of an overall environmental impact than polyester fill.

High-end brands Moncler and comforter maker Coyuchi exclusively use down, touting its “natural” and “organic” origins.

In 2023, virgin down certified by RDS equaled 3.3 percent of the overall market, according to the nonprofit Textile Exchange. It runs the standard, which The North Face initiated in 2014. The RDS chain of custody process includes site audits and certification along the supply chain. H&M, REI, Arc’teryx, Canada Goose and Marmot are among the 200 brands using RDS to reflect humane treatment involved in down production. RDS-certified down production grew from 19,233 tonnes in 2022 to 20,639 tonnes in 2023.

Another standard, run by Control Union of Amsterdam, also disallows force-feeding and live plucking. Patagonia helped to create the Advanced Global Traceable Down Standard (TDS) in 2015. In addition, the Down Integrity System & Traceability protocol emerged from Moncler in 2014. Downpass is a German standard.

The problem with synthetics

The market for down may grow at a brisker pace than that of synthetics, but polyester staple fiber sales are measured in billions, not millions.

- Sales for down and feathers reached $87 billion in 2021 and will rise by 8 percent each year to $188 in 2031, Business Research Insights reported.

- The $67 billion annual market for polyester staple fiber, stuffed into jackets and bedding, will reach $111 billion in 2032, also according to Business Research Insights. That’s compound annual growth of 5.7 percent.

For brands, generic polyester staple fiber for jacket fill comes at a fraction of the cost of down. RDS-certified down brings an additional premium.

PrimaLoft, ThermoLite, Thinsulate, Heatseeker, Coreloft, Plumafill, Cirrus, 3M Featherless Insulation, Omni-Heat insulation, Loftech, Thermoball. These are all fancy names for polyester-based fill materials.

Polyester comes from ethylene and propylene, which come from refining crude oil and natural gas. Dow Chemical, ExxonMobil and BASF are major producers of the gases.

Some companies are attempting to lighten the impacts of their petrochemical fills:

- The fibers of ThermoLite EcoMade, from the Lycra Company of Wilmington, Delaware, come from either recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles or textile waste.

- Bernardo Fashions uses Ecoplume fill, recycled polyester from water bottles, in its puffer jackets. Ecodown says it’s keeping plastic waste out of the oceans.

- PrimaLoft Bio synthetic fibers are supposed to biodegrade in 973 days under conditions similar to the ocean. “Only materials found in nature, like water, CO2, methane, biomass and humus” are left behind, according to PrimaLoft of Latham, New York.

Yet, regardless of whether polyester is kept out of nature or recycled, apparel sustainability experts have raised concerns about the long tail of polyester microfibers. The Textile Exchange advocates for companies favoring synthetics to choose recycled or biomaterial choices.

“We believe it is essential to stop new fossil-based materials from entering the system if the fashion industry is to reduce its emissions and meet climate goals, meaning that the industry should avoid virgin, fossil-based alternatives to down,” a spokeswoman for the Textile Exchange said.

Some of the above?

“For the industry to meet its climate and nature goals including the reduction of GHG emission by 45 percent, while creating beneficial impacts for animals, people and planet, the industry needs a diverse portfolio of preferred fibers and a reduction of new synthetic material,” Erfan added.

The nonprofit runs RDS and other standards to improve the textile industry’s raw material sourcing. The Textile Exchange holds the position that animal-derived materials are suitable if “measures can be taken to prevent unnecessary harm to animals.”

Many companies, including Patagonia, H&M, The North Face, Arc’teryx, Marmot and Rab, source both down and petroleum fill. Canada Goose also uses tencel and synthetic fill. Its garments comprise 80 percent “preferred fibers and materials” (PFMs), a Textile Exchange definition for the relative sustainability of garment fibers. Bedding brands using down and polyester include the Company Store, Martha Stewart, Ralph Lauren, Brooklinen and Parachute Home.

Patagonia, which popularized fossil fuel-based fleece, plans to abandon virgin petroleum by 2025. It used 190,000 pounds of recycled down this fall, reducing CO2 emissions by one-third over virgin feathers, according to the brand.

Going vegan

Yet other brands are embracing alternative materials that neither derive from animals nor fossil fuels. Some are in pilot testing or capsule collections, but others are slowly reaching the mainstream.

Avocado’s pillows and Vaude’s sleeping bags use “silk cotton” kapok, from a tropical tree. Houdini Sportswear, Cotopaxi and Buffy use the semi-synthetic Tencel, made by Lenzing with wood pulp fibers. Bedding by Ettitude uses bamboo-based lyocell, an alternative to Tencel. Cotton and recycled fibers are yet other non-down options.

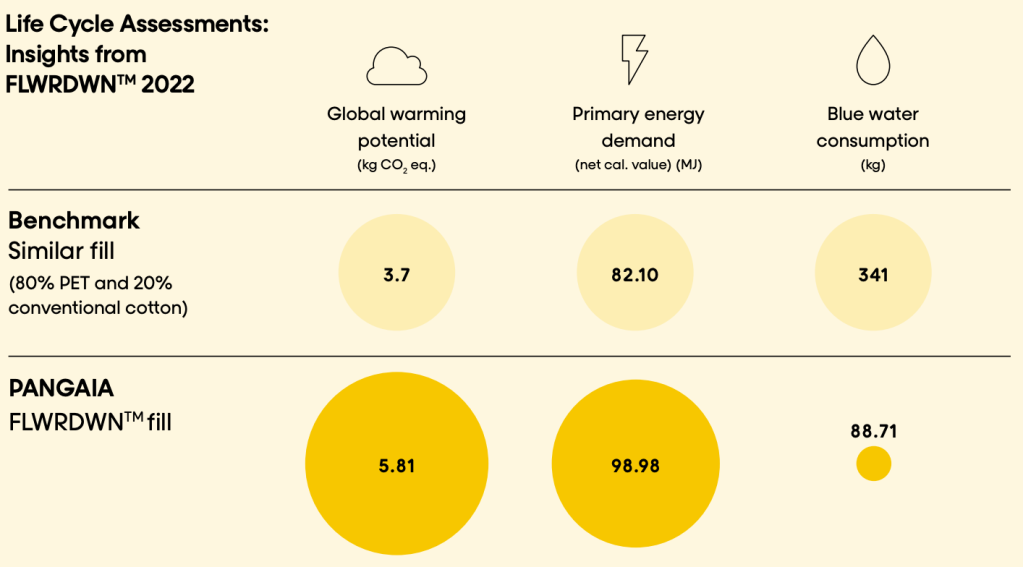

Pangaia created and uses FLWRDWN, which H&M is embracing. Pangaia reported in 2022 from a lifecycle assessment of its FLWRDWN that a polyester-cotton blended fill had a lower carbon end energy footprint, although water consumption was higher. In 2023, the company reported that FLWRDWN was more favorable across the board than goose down.

“Biobased materials tend to consume a lot of water because of agriculture, and aerogels production can be energy-intensive due to the drying step, and may involve the use of harsh solvents during production,” said Marcian Lee, a materials analyst at Planet Tracker, said of FLWRDWN’s footprint.

Will down follow the path of fur in public opinion?

Anti-fur activists have squirted fake blood on fur wearers. Climate activists have splashed tomato soup on Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers.” But no protestors are tossing liquids onto down or polyester jackets — yet.

Using down may expose brands to shareholder activism by animal welfare advocates. Microfiber plastic pollution, including from fossil fuel fabrics, however, poses a long-term risk of litigation, according to the Planet Tracker think tank. Brands must also weigh how these materials impact their emissions and net zero goals.

“It’s tricky to say which option has the lowest risk” among the animal-based, fossil-based or plant-based options, but recycled materials are generally recognized as more sustainable than virgin ones, Planet Tracker’s Lee said.

“You can’t please everybody, so someone’s bound to get upset (PETA vs. anti-plastic vs. agri advocates vs. other environmentalists, etc.) regardless of your choice, so I think it ultimately depends on what option aligns best with the company’s brand image,” he added.

CORRECTION: This story was updated to reflect that NSF no longer runs a down standard.