It's time to measure business success beyond profit

A new measure for the success of business enterprises and those who lead and manage them. Read More

The following is an excerpt from the book “Digging Deeper: How Purpose-Driver Enterprises Create Real Value,” by Dietmar Sternad, James J. Kennelly and Finbarr Bradley, published by Greenleaf Publishing.

How do we measure the success of any business enterprise and those who lead and manage it? The dominant view — strongly influenced by the doctrine of shareholder primacy — is that increasing the wealth of shareholders through profit maximization and an increased share price should be the one and only objective of a business.

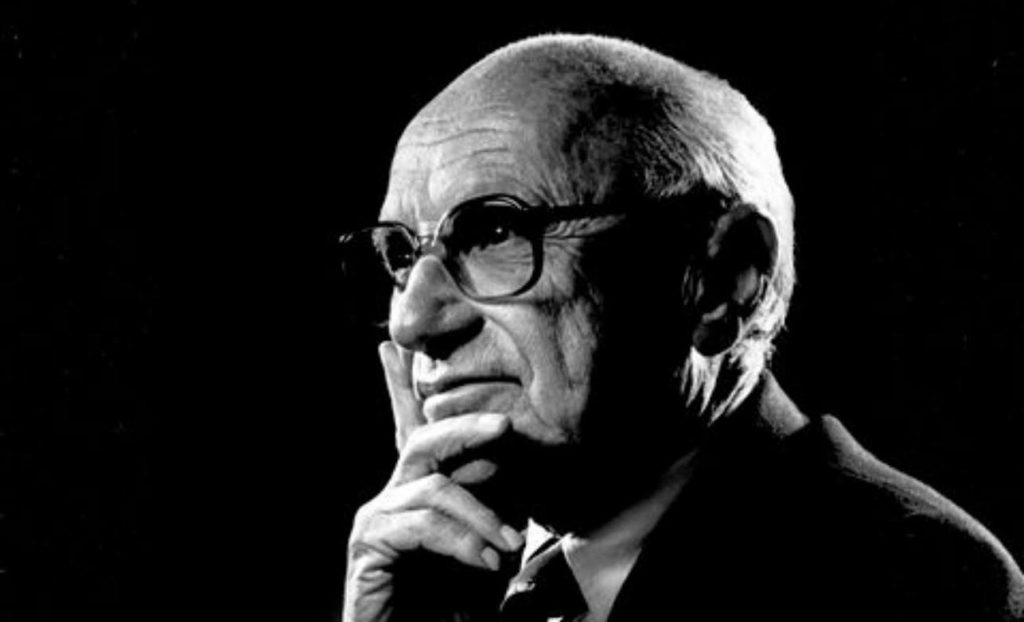

Michael C. Jensen, a fierce advocate of the shareholder value paradigm argues that “multiple objectives is no objective” and dismisses leaders who actively try to balance the needs of different stakeholder groups as “self-interested managers” who “destroy firm-value” as they “pursue their own interests at the expense of society and the firm’s financial claimants.” At base, this is really not so different from Milton Friedman’s well-known argument in which he claimed that managers who pursued any goal other than profit were “unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.”

Let us pause for a moment and pose this question: Do the people and enterprises who decide to follow a deeper purpose than just making money really destroy value? Do they really work “at the expense of society” as they care for the well-being of their non-shareholder stakeholders? Are those who try to balance the interests of different stakeholders really the ones who are in thrall to their own narrow “self-interests”? Such questions border on the ludicrous.

Of course, our answers to these questions depend on how we define value. If we believe that the essential, fundamental value is monetary value — and that the lure of money drives every type of productive (or “valuable”) behavior, as some advocates of the shareholder value paradigm would have us believe — then (money) value maximization might really be the narrow ultimate purpose of business as Jensen postulates.

As such, it would naturally be the only measure of managerial success. But if we focus on a definition of real value that goes well beyond the narrow conceptualization of monetary value, then the picture that emerges is very different. If we understand that relatively few of the elements of a good quality of life — such as living in an intact natural environment, having rich and authentic social interactions in authentic communities, finding meaning in one’s life — can actually be monetized, then the idea of money value maximization as the only legitimate goal of a business is simply untenable.

Businesses are a means for the provision of goods and services. They need to make profits — at least over time — to be sustainable. But beyond that, there is no natural (or man-made) law that precludes them from following a deeper purpose. They can choose to attempt to maximize social welfare under the constraint that profit needs to stay within a certain range, they can put weights on monetary versus non-monetary objectives, or can try to combine the two in a synergistic way.

It is a conscious decision that owners and managers need to take together, not a God-given precept that gives money-making (or shareholder value) overarching preference. Why should striving for a balance between profitability (the life-sustaining “blood” of an enterprise) and creating real value (the “heart” of an enterprise) not be a legitimate managerial goal, and one for which managers should be held accountable? What use is blood if no heart beats?

We can hear the skeptics asking, but aren’t profits and market value the hard currency, the tangible “yardstick” by which managers can and should be measured while the deeper, emotional side of value must remain elusive and vague, and thus more or less unmanageable? Shouldn’t we focus on that which we can count, and stay away from that which is dense, complicated and tricky?

Let’s keep it simple and clear, they say! This is a common argument of those who would have us believe that profits and share prices have always been the end-all and be-all and in fact the only objective measure of business success.

However, commercial activity and business enterprises were much in evidence long before the invention of double-entry accounting by Fra Luca Pacioli in Florence in 1494. Before then, of course, it was impossible to calculate profits in the way we do now. And the oldest book about the stock exchange business — a work by José de la Vega with the prophetic title “Confusion of Confusions” — was published only in 1688. The New York Stock Exchange itself was founded in 1792, so clearly stock prices as the “ultimate yardstick” for business success have not existed forever either.

Just as those yardsticks were developed over time, through societal dialogue and in response to contemporary conditions and needs, we also have the capacity to develop new yardsticks for tomorrow’s businesses. And we must. The roots of real value creation described in our book “Digging Deeper: How Purpose-Driven Enterprises Create Real Value” can be a starting point.

We can assess managerial long-term orientation with a focus on non-financial leading indicators rather than quarterly results; we can assess relationship-orientation with the average retention rates of suppliers, customers or employees; we can assess limits recognition with social and environmental performance indicators that are already used in corporate sustainability reports; we can assess the extent to which an enterprise is a learning community with the time that employees spend in learning activities.

We can indeed quantify outcomes in real value terms: for example, the number of quality jobs that are created in a certain region, the degree to which employees find their work meaningful, or customers’ perceptions of the emotional value that they get from the products or services of the firm. These are just a few examples, and by no means exhaustive.

And admittedly, all measures, including these, are likely to be imperfect. But these examples suggest that we can find ways to assess both the input factors and outcomes of real value creation — but only if we really want to. Even more important than the hard currency of numbers is the ability, and the desire, to begin an honest dialogue on the real value that firms create — or fail to create. What we really need is a new way of talking about business.

“A new narrative is emerging in society,” says R. Edward Freeman, who is widely renowned for his pioneering work on stakeholder theory. At a recent conference in Hamburg he argued that the old story was that business was all about money, but now “the new narrative of business is purpose and passion.” He is so right and it is long overdue. We need a new narrative about business at both the level of the individual firm, and at the societal level. It is time for the economy (and its businesses) to work for society, rather than the other way around.

We have the power to decide whether we want to tell a story of business as a profit-making engine in which selfish individuals strive to maximize their individual money value, and the rest get the crumbs from the table, or if we want to tell a different story — the story of business as a vehicle for improving our quality of life and the prosperity of society.

Who are our heroes? The wolves of Wall Street or the responsible entrepreneurs who follow a deeper purpose? Who gets media attention and the most political support — the untethered, opportunistic investment bankers and derivatives dealers or the creators of real value who respect the limits of both people and the environment?

Do we want to educate our future leaders as well-oiled self-interest-seeking machines or as responsible, holistic long-term thinkers who pursue profit along with the common good? It is up to us to decide. We can create an alternative — if we just start thinking and talking about it. Indeed, some enterprises are already “walking the walk.” We will need to quicken our pace to catch up with them.