Blame leather, cashmere and wool for most methane in fashion, report says

Virgin animal materials create an outsize share of methane, but alternatives for large global supply chains aren't available yet. Read More

- In methane pollution, leather, wool and cashmere far exceed their 3.8 percent share of overall materials, according to Collective Fashion Justice.

- Reducing methane by shifting to recycled, plant-based or next-gen fibers offers quick and critical climate benefits.

- Backers of animal-based materials say that sustainable and regenerative practices can address or prevent emissions.

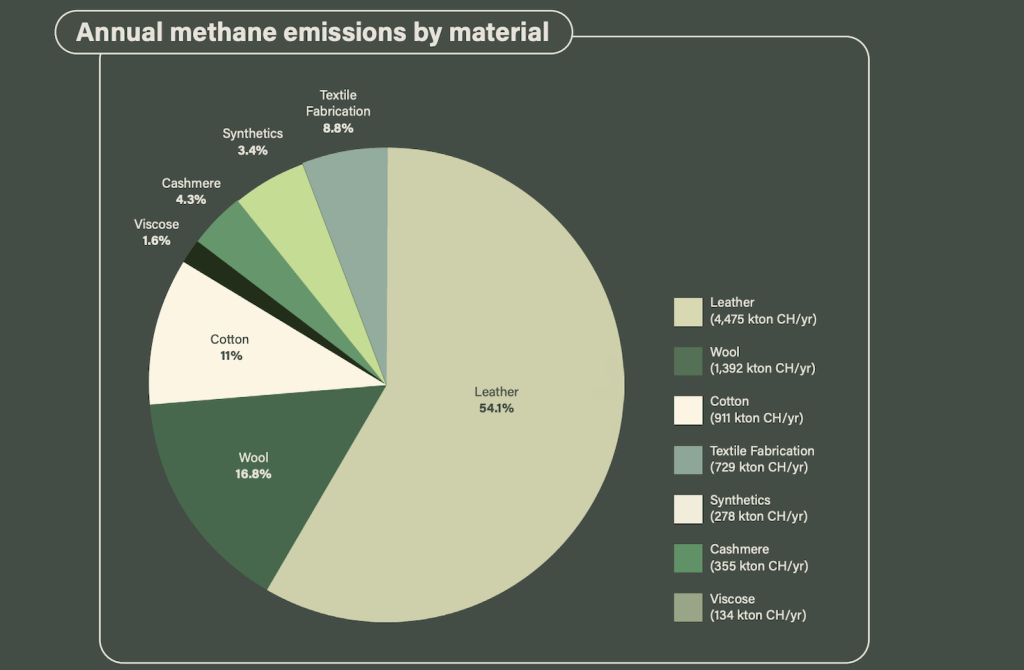

Cows, sheep and goats are culpable for most of fashion’s methane emissions, according to a new report. Leather, wool and cashmere produce 75 percent of the industry’s super-pollutant although they only make up 3.8 percent of its overall materials, the nonprofit Collective Fashion Justice has found.

There’s been scant focus on fashion’s methane footprint, as net-zero efforts mostly center on carbon dioxide. However, if the industry fails to slash methane by at least 30 percent, those emissions will be equivalent to the emissions of France in 20 years, warned the Sept. 15 report, “Now or never: A first methane footprint for the fashion industry.”

Although methane has caused 30 percent of the total rise in the planet’s temperature, cuts now can deliver faster near-term reductions. (Methane heats the atmosphere about 85 times as much as a ton of CO2 does in their first two decades of their existence, but CO2 is 30 times worse over a century.)

And as brands have churned out more fashions, faster, over the past half decade, the industry’s greenhouse gas emissions from raw materials leaped by 20 percent, according to the Textile Exchange’s 2025 Materials Market report released Sept. 18.

Collective Fashion Justice urges businesses to opt for recycled sources instead of new animal products. “When we look at a whole host of environmental factors, recycled wool, plant-based materials and other non-animal and non-fossil materials typically perform far better overall,” said Emma Håkansson, the group’s founder and director.

The fix?

The organization’s findings — and its call to halt the use of virgin materials — continue longstanding debates over the lifecycle impacts of raising animals for leather and textiles. They also raise the question of what brands can realistically achieve today, given the relative scarcity of lower-carbon materials.

The report also called for industry to support innovators in “next-generation” fibers based on plants, fungi and waste. However, these are mostly unavailable at scale now. Less than 1 percent of all fibers derive from textile-to-textile recycling.

Nor should companies favor fossil synthetics instead, Håkansson added. “This is not an either-or situation. We must move beyond our reliance on both of these unsustainable material sources,” she said.

Moreover, Håkansson says that even when brands use third-party certified, climate-friendly practices — standards from the Leather Working Group, Responsible Wool and Good Cashmere — very little is improved. With wool, for instance, they neither address the land footprint nor the methane from sheep exhaling and passing gas, in her estimation. The same applies to leather, which depending on one’s perspective is either an innocent byproduct or an enabling “co-product” of the beef industry.

On the other hand

Collective Fashion Justice, an Australian advocacy group with a longtime focus on animal welfare, engaged researchers from Cornell University and New York University on the methodology.

That said, some experts take issue with the report’s conclusions.

Methane is important but needs to be contextualized relative to the industry’s total greenhouse gas footprint, according to Joël Mertens, director of Higg Product tools at Cascale. The Oakland, California, nonprofit, formerly the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, counts large brands among its 300 member organizations.

“Within that context,” said Mertens, “the total greenhouse gas emissions of animal-derived raw materials (including sheep wool, cashmere and leather) account for a much smaller portion of industry emissions; just under 3.5 percent. By comparison, impacts relating to garment manufacturing are 8 percent, and textile dyeing and finishing are 55 percent.”

Lightening leather

Leather creates 54 percent of the industry’s methane, followed by 16.8 percent for wool and 4.3 percent for cashmere, according to Collective Fashion Justice.

Leather uses waste hides from the beef industry, which the United Nations says is responsible for 14 percent of global climate emissions. Most of its footprint comes from cattle raising, which drives deforestation. Tanning and finishing bring more pollution.

Fashion businesses addressing those impacts include Coach, part of the Tapestry group, and Dr Martens, by buying “wet blue” hides leftover from beef, from U.K. startup Gen Phoenix.

And numerous innovators are engineering new materials to mimic leather by using mycelium, apples and cacti, but still in small volumes.

Woolly impacts

Wool comprises .9 percent of fibers in fashion but spews disproportionate emissions and hurts biodiversity, according to the methane report.

John Roberts, managing director of Woolmark in Australia, begs to differ. “Wool is a natural, renewable, biodegradable and recyclable fiber,” he said. Producers are exploring feed additives such as algae, as well as sheep breeding and farm efficiencies to cut emissions.

The beef industry is, too. However, wool differs from chemically intensive leather making.

“Wool itself is composed of 50 percent organic carbon by weight, which is naturally sequestered from the atmosphere by the plants that sheep eat,” said Nica Rabinowitz, the Climate Beneficial Verified and supply chain development manager of Fibershed, which helps farmers adopt regenerative practices.

Recycled wool slashes CO2 by 94 percent compared with virgin fiber, according to Patagonia. The brand, alongside VF Corporation’s Smartwool and Icebreaker, is also among the larger buyers of Responsible Wool Standard wool.

In other second-life wool practices, Eileen Fisher patches and reworks marred sweaters and sources recycled material from ReVerso in Italy, which also sells to Patagonia, Gucci and Stella McCartney.

Cutting cashmere

Cashmere is only found in .02 percent of materials in fashion, according to the Textile Exchange. However, the fiber has a far greater methane intensity per kilogram than leather and wool, the report found.

Among brands tackling its footprint: Los Angeles-area company Reformation eliminated virgin cashmere entirely from its collections. It sources deadstock for sweaters and trims.

And one more thing

Beyond the materials, Collective Fashion Justice demanded for companies to tackle the 20 percent of fashion’s methane, which comes from material processing and fabrication in supply chains that rely heavily on coal and gas.

“Brands must also switch to renewables across their value chains and support manufacturing partners to do so,” Håkansson said.

Efforts in progress include the Future Supplier Initiative by the Fashion Pact and the Apparel Impact Institute, which have signed on H&M, Group, Gap and others to directly fund suppliers’ renewable energy transitions.

Subscribe to Trellis Briefing

Featured Reports

The Premier Event for Sustainable Business Leaders