More businesses mine gold from America’s closets

The booming apparel resale market is encouraging news for the fashion industry, consumers and the environment. Read More

It may take a moonshot to rebuild a crop-to-garment fashion economy in the United States. But a “circular” apparel market is fast maturing that mines the nation’s closets for its supply chain and leaves a relatively light footprint on nature.

Indeed, by most accounts, secondhand markets are flourishing. One of the most aggressive estimates, from CapitalOne Shopping Research, shows that resale has skyrocketed by 400 percent in the U.S. between 2018 and 2023. Traditional thrifting and donation-based resale also grew, although by a lesser, yet respectable, 21 percent. That’s good news to sustainability advocates who seek to slow the pollution that fast fashion practices have multiplied in recent decades. Textile waste, for example, rose by 50 percent between 2000 to 2018, according to the U.S. government’s first report on the topic, published in December.

Two especially encouraging facts on this front:

- The climate and energy impacts of purchasing used apparel are 42 percent lower than buying new, according to recent research in the Journal of Circular Economy.

- Buying secondhand saves more than eight pounds of CO2 and 89 gallons of water per item, according to CapitalOne.

As it keeps materials out of landfills, the online fashion resale economy also carries low overhead for businesses and attracts price-aware shoppers. These are just two reasons why industry experts expect the $53 billion secondhand market to thrive, even in the face of new tariffs, continued inflation or a potential recession.

Patagonia, Dr. Martens, Eileen Fisher and dozens of other brands are increasingly leveraging online storefronts as a core strategy to extend the lives of their jackets, boots and blouses. Resale serves corporate sustainability goals and deepens shoppers’ brand relationships, too.

Over the past half decade, third parties have cemented their niche within this growing ecosystem. They include thrifting platform ThredUp and reverse-logistics players Trove, Archive and Tersus Solutions. In addition, textile and waste regulations emerging in California and New York are driving urgency and even creating new business opportunities.

All of which is hopeful news for a sector that created 100 billion garments in 2020 — twice as many as in 2000 — 40 percent of which went unsold, according to the United Nations Environment Program.

The rise of resale

Resale shines in what is an otherwise dim fashion industry landscape. It will comprise 10 percent of overall sales in 2025, McKinsey’s annual State of Fashion report projected last November.

In addition, according to ThredUp’s 2024 resale report:

- Secondhand clothing sales grew by 18 percent in 2023 globally, and are projected to expand 12 percent annually through 2028. That’s three times faster than the apparel market overall, most of that increase expected to come from new customers.

- In the U.S., online secondhand sales rose by 23 percent in 2023. That channel is likely to make up half of all domestic spending on used apparel in 2025.

- In 2023, branded resale grew by 31 percent, and 74 percent of retail executives without resale programs were considering one.

A shift in consumer mindset, especially among young adults, as well as evolving e-commerce and machine learning tools, has birthed a resale renaissance of sorts, according to Cynthia Power, owner of apparel consultancy Molte Volte in Ossining, New York. “I like how many different varieties of participation you have. You can be the thrifter, you can do the vintage stores, you can do the consignment, you can go really high end, or even higher,” she said.

The number of brands selling their apparel online grew from 36 in 2021 to 157 in 2023, according to Statista.

A natural fit

In a review of sell-through rates and listing volumes for 55,000 brands in its digital marketplace, ThredUp named Lululemon Athletica, Patagonia, Vuori, Reformation and Free People as the five “best brands in resale.” Eileen Fisher, with its high-quality, high-priced garments, was an early adopter.

Outdoor brands hung resale e-commerce shingles earlier than others. In addition to Patagonia’s Worn Wear options, steep discounts on used subzero jackets abound at The North Face Renewed, REI Re/Supply and Arc’teryx ReGear. Even fast fashion players Zara, H&M and Shein have launched in-house resale.

The overall market share of branded resale is unknown, but estimates place it between 1 and 3 percent of participating brands’ sales. Yet even if resale makes up, say, $100 million of a multibillion-dollar brand’s sales, that’s still equivalent to a successful midsize business, noted Power.

“Brands and retailers have found that [resale] has not cannibalized their regular sales as much as they feared that it might,” said Margaret Bishop, a professor at Parsons School of Design in New York.

Womenswear maker M.M. LaFleur, as an example, reported 3 percent revenue growth in the first year after launching peer-to-peer online resale enabled by Archive in 2021.

Evolving tools

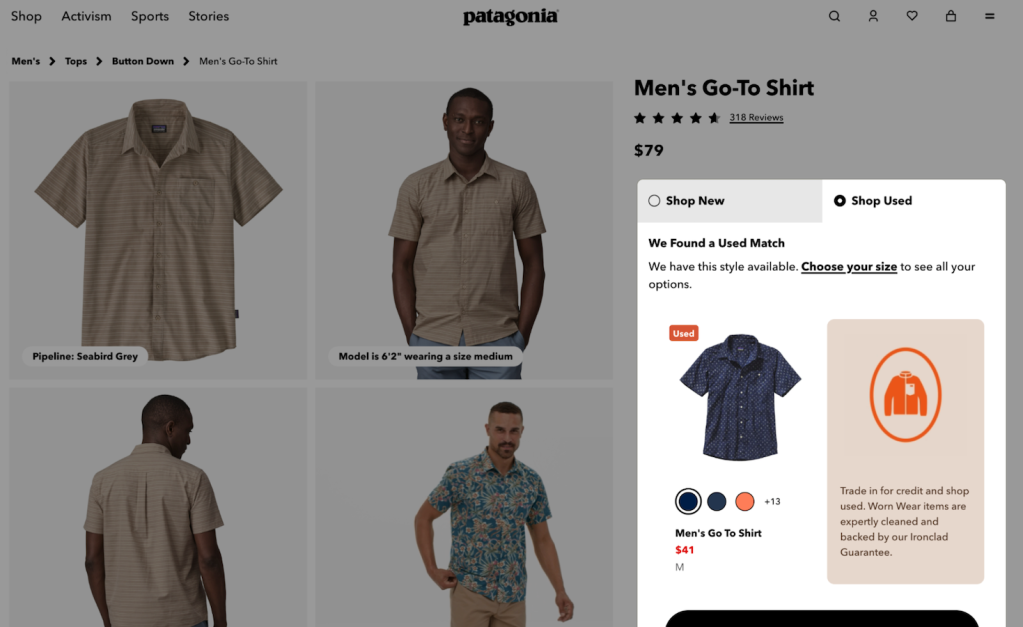

Brands initially segregated their resale and new digital storefronts, but that’s shifting. Patagonia last fall started surfacing Worn Wear items alongside related search results for new garments, using a plugin from e-commerce logistics backbone Trove. The Brisbane, California, startup has cornered about three-quarters of the branded resale market since purchasing competitor Recurate in August.

Sustainability teams initially pushed their brands to online resale. “But the other parts of the company are coming to the table, the (general managers), the (e-commerce) managers, the fulfillment folks, and so the sustainability person is getting a little more help than they used to,” said Trove CEO Terry Boyle.

Companies can grade returned items based on their condition and resell them in close to real time, Boyle said. “These are the types of things that once would have been put on pallets and sold at bulk, like once a year for 10 cents on the dollar. Now they’re getting a lot more money.”

Trove and competitor Archive do for brands what ThredUp does for itself as a marketplace for 60,000 brands. Based in Oakland, California, the public company also helps brands with their own resale channels.

ThredUp took the thrift-store model virtual in 2009, giving people polka-dot “closet cleanout” bags to mail in old stuff in exchange for post-sale store credit. It followed in the steps of social marketplaces such as eBay and Craigslist, which effectively obviate brands from their insular economies.

By 2011, Poshmark, The RealReal and Depop had emerged to take sales cuts of the vintage or luxury fashions on their platforms. Meanwhile, thrifting giant Goodwill, whose online sales date to 1999, created a curated online marketplace in 2022.

In the past decade, fashion brands started to recapture some revenue lost to third parties. Patagonia launched Worn Wear in-house in 2017. Trove, which began in 2012 as a peer-to-peer service, shifted to provide the resale software backbone to Patagonia, and soon thereafter for Eileen Fisher and REI.

As more brands get involved, growth in multibrand resale platforms could be cooling. For instance, an estimate of $80 billion in revenues for 2024 by eMarketer fell $8 billion short of its earlier forecast.

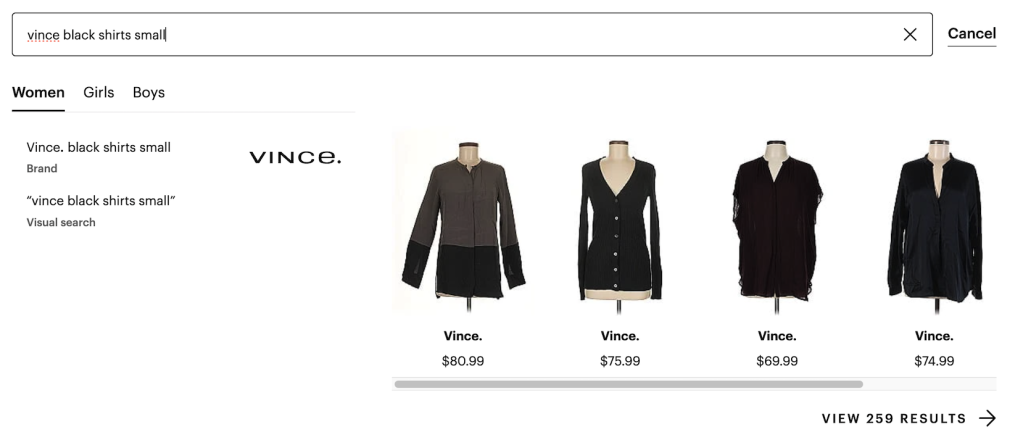

All of the merchants keep tweaking their tools for a competitive edge. ThredUp recently expanded its AI-based image and natural language searches. For example, “Vince black shirts small” retrieves 259 results. ThredUp’s use of a single SKU (stock keeping unit) per item on the backend helps shoppers quickly find clothes with specific attributes, according to Alon Rotem, ThredUp’s chief strategy officer and general counsel.

“And then when you add digital ID technology that other companies are working on,” he said, “it’s like all of a sudden you’re leveling the playing field between traditional, linear retail and circular resale.”

The North Face, REI, New Balance, Dr. Martens and smaller brands have been profiting from resale for several years, according to Peter Whitcomb, CEO of Tersus Solutions. More companies are understanding the benefits of having a sustainable, always-on, domestic source of inventory, he added.

Tersus is the “picks and shovels” counterpart to software players such as Trove and Archive. The Englewood, Colorado, company uses liquid CO2 to de-grime shoes and spruce up shirts. Whitcomb anticipates processing a million units of used stuff this year.

The common brand misconception that resale is dilutive, hard to do and unprofitable does not stand up to scrutiny, he added. “There are viable ways to do it,” he said. “The software has gotten better. We’ve gotten better in ops.”

Legislative tailwinds

Related to California’s Responsible Textile Recovery Act, a group of that state’s legislators visited Tersus last year to understand its approach to apparel recycling and reusability. The law, which came into effect in January, requires brands to work with producer responsibility organizations (PROs) to provide free recycling and take-back programs by 2026.

ThredUp’s Rotem believes that California’s extended producer responsibility (EPR) law represents a real opportunity for his company: “We should be a service provider to the PROs who are [asking], what are we actually going to end up doing with this clothing? Where should we send it?'”

That law, together with a related bill in New York and a suite of related policies in the European Union, are driving brands to get ahead of compliance and capture their secondhand markets, according to Emily Gittins, CEO of Archive, a Trove competitor. Archive counts 50 brand clients in 10 countries, and it’s expanding globally. The San Francisco startup announced $30 million in Series B funding in early February.

Steve Preston, president and CEO of Goodwill Industries International, sees opportunities for national partnerships to help retailers and brands manage returns and overstock goods. “We provide a perfect solution for them,” he said, “and in many cases they’re concerned about the same sustainability issues we are.”

Online sales represent a relatively faster-growing portion of Goodwill’s revenues, Preston said, but do not drive growth overall. But if consumer prices spike upward, he added, the value proposition for the Rockville, Maryland, organization’s regional nonprofits and other resellers will rise.

[Join over 1,500 professionals transforming how we make, sell, and circulate products at Circularity, April 29-May 1, Denver.]