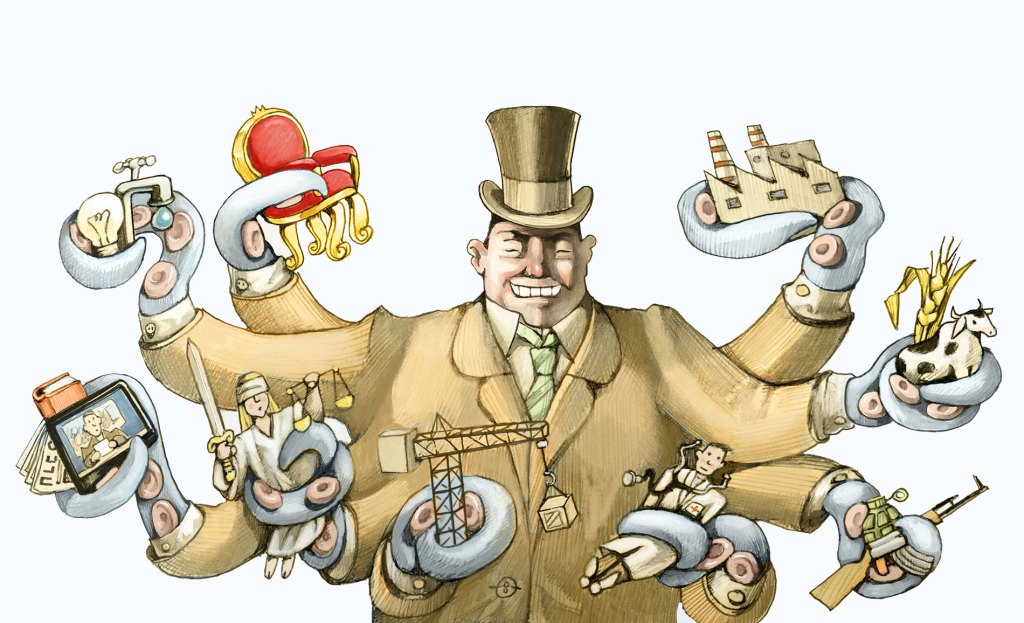

Preparing for a capitalism reset

Market-based capitalism is increasingly less fit for serving contemporary society’s purposes. What to do? Read More

Shutterstock

After several decades of continuing economic crises brought on by a narrow ideological approach to risk and reward, inept corporate governance, ineffective regulatory oversight and excessive short-termism, market-based capitalism is increasingly less fit for serving contemporary society’s purposes.

Leading this critique is a group of more diverse (in gender, geography and sometimes age) economic thinkers. Their careers, values and life experiences differentiate them considerably from their peers embedded in corporate boards, the U.S. Treasury Department, Federal Reserve Board, The World Bank, International Monetary Fund, European Central Bank, Bundesbank or the major investment houses of New York, London, Frankfurt or Tokyo. They include Mariana Mazzucato, Kate Raworth, Rebecca Henderson, John Elkington, Anand Giridharadas and Steven Pearlstein. They and many others articulate an agenda for preparing a capitalism reset.

Widening chasm

At least six systemic factors have kneecapped capitalism’s performance and credibility in recent decades:

- A growing number of business sectors exhibit a winner-take-all concentration of economic power, thereby increasing barriers to entry, reducing innovation and blocking government oversight. From 1997 to 2012, for example, the four largest firms in every major sector expanded their percentage of that sector’s revenues from 26 percent to 32 percent.

- Major business and societal risks are not accounted for in materiality and other assessments of risk. Supply-chain disruptions, access to talent and nationalistic trade policies have caught the attention of growing numbers of enterprise leaders. Factors such as climate change acceleration, pandemics, the inefficiencies of low-quality infrastructure and the degradation of democracy (and its impact upon business) have not. A 2016 International Monetary Fund working paper concluded that rising inequality accounted for nearly half of the decline of trust in the United States between 1980 and 2000.

- Capitalism’s major proponents continue to use price as the measure of value. In doing so, they’ve contributed to the financialization of the economy in which asset managers displace people and productivity, regard rents as more valuable than R&D, innovation and skills, and reward value extraction more than value creation through improved goods and services.

- Inequality as a deliberate business and public policy choice has undermined popular acceptance of capitalism. As Rebecca Henderson notes in “Reimaging Capitalism in a World on Fire,” between 1980 and 2014 the income of the poorest half of the U.S. population grew by only 1 percent, while the income of the top 10 percent expanded by 121 percent, and the income of the top 1 percent more than tripled. Average CEO pay, which averaged 30 times worker compensation in 1978, skyrocketed to 312 times that amount in 2017. Steven Pearlstein, in his 2018 book “Can American Capitalism Survive?” concludes that if the distribution of U.S. income had remained the same in the decades after 1980 as in prior years, rising wages virtually would have eliminated poverty.

- There are no side effects, only effects. As evaluated by systems analyst John Sherman, unconstrained markets redefine their boundary zones so that important factors are not counted. In a global economy valued through the short-term lens of price and decided through the perspective of shareholder value, resources for preventive public health surveillance, public education, modernized transportation infrastructure and environmental protection are not valued and go unallocated.

- Business leaders increasingly demonstrate a lack of confidence in contemporary capitalism. Confidence among elites is vital to sustaining any belief system. When Mikhail Gorbachev’s Soviet Union collapsed (absent a conflagration) in 1991, historian Stephen Kotkin attributed this shocking phenomenon in part to a “vast and self-indulgent” Soviet elite’s abandonment of belief in the system they were tasked with administering. When the Business Roundtable issued its August 2019 statement to redefine the purpose of a corporation, it did not represent a vanguard to promote a more equitable, sustainable society (a more improbable organization to create such a blueprint could not be found). Rather, it produced a de facto concession that defending their corporate perimeters based upon shareholder value was becoming less defensible. BRT’s statement represents a bland testimonial without action, and it concedes that the CEOs that approved it don’t have confidence they have an improved alternative through which to engage society in conversation.

Redesigning capitalism

Beginning in the late 19th century, the rules for conducting capitalism have represented a contest for power between its unleashed “animal spirits” and society’s need for adult supervision through public oversight. The momentum for additional supervision is once again on the rise. How can it be designed without sacrificing the benefits of the enormous wealth capitalism is capable of generating? Several initiatives are offered below:

Convening asset managers at market scale to align their expectations for enterprise performance. This is a useful role that Larry Fink of BlackRock could perform along with his colleagues from Vanguard and State Street, the other two large asset management firms. As Fink has moved beyond writing mere exhortatory letters to CEOs to actually voting against management on companies’ climate performance at annual shareholder meetings, he could convene a set of roundtables involving the major asset management firms.

The roundtables could achieve the following useful outcomes: identifying the critical sustainable business performance issues for evaluating the investment worthiness of managements and corporate boards (example issues would include climate change, deforestation/biodiversity, renewable energy use, workforce diversity and human capital development, and advancement of a more equitable civil society); and developing a select number of business-relevant performance metrics for each priority issue. The roundtables should provide collaboration opportunities with selected academic experts and non-governmental organizations. Participants should be chosen based upon knowledge, experience and diversity criteria. Special consideration should be given to incentivizing longer-term business investment and performance.

Reviving a more vigorous antitrust policy to promote competition. Federal antitrust reviews and cases involving large companies have dramatically declined since the 1990s. This development coincided with the increased concentration among business sectors as varied as airlines, beer, cable television, information technology, pharmaceuticals and agricultural seeds and pesticides. Between 1997 and 2012, 75 percent of industry sectors experienced increased concentration.

Such aggregation has been especially pronounced in the technology sector through the formation and growth of industry giants such as Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google, which increasingly experience no effective competition. As companies grow larger, notes Columbia Law School Professor Tim Wu, their bigness is less associated with operational efficiencies than with an ability to wield economic and political power. Original Facebook investor Roger McNamee has called out the company’s efforts to stymie competition and slow the pace of innovation as part of his argument to break it up into smaller, more competitive enterprises.

Advancing value chain governance. The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly exposed the numerous business risks embedded in global supply chains for such vital products as pharmaceuticals, masks and personal protective equipment. Similar vulnerabilities existed following the 2011 tsunami that disrupted auto manufacturing for a number of Japanese firms. More recently, advancing deforestation in Brazil follows the trail of expanded beef production to serve growing world demand, while accelerating water scarcities in various regions of the world challenge both businesses and communities to satisfy their respective needs.

Various initiatives and collaborative efforts have emerged in recent years to raise supplier training and performance standards, improve living wages, limit child labor and protect natural resources. Virtually none has advanced to global scale, nor have they adopted a global governance approach that seeks to unify the interests of suppliers, major producers and their downstream customers. Global value chain governance, initiated by leading companies while observing appropriate antitrust considerations and practicing transparency, is a necessary step in making capitalism more fit for purpose. Government policies subsequently can adopt and periodically update value chain performance standards.

Aligning the entrepreneurial state with the interests of the private sector. The myth that the private sector is the sole or predominant engine of innovation effectively was exploded in 2013 with the publication of Mariana Mazzucato’s book “The Entrepreneurial State.” Her argument is that the post-World War II economic success of the United States was due in large part to public sector investments in basic research and subsequent technology development prior to commercialization by the private sector.

While taking nothing away from the entrepreneurial, manufacturing and marketing skills of private businesses, government funding laid the technological foundations that were beyond business means or interests in such sectors as aircraft manufacturing, information technology, pharmaceuticals and telecommunications. Analogous public investments continue to this day in the search for a pandemic vaccine, advanced battery designs for electric vehicles and a host of smart technologies. Given this mutuality of need and interest, it is timely to stimulate a renewed public debate for public- and private-sector collaboration, articulate the benefits of such collaboration to employees and citizens, and develop appropriate accountability and transparency commitments to ensure that government funding is not mere tax free transfer payments or subsidies to private companies.

Making the business case for democracy. Business interests always have participated in representative democracy. This occurs through a variety of forms — funding for candidates and political parties, supporting referenda on issues important to the business community (tax policy, immigration, environmental policy), direct lobbying of elected representatives and executive branch agencies, and providing philanthropy investments for education or academic or think tank programs to reinforce its point of view on regulation. Since the end of the Cold War, rarely have the representatives of capitalism directly articulated or supported the case for democracy. Nor has the business community acknowledged that markets function best in democratic political systems.

As authoritarian and populist regimes gain influence, and as partisan divides polarize Americans and confuse their understanding of democratic forms of expression, the need for business participation in democracy becomes more urgent, if only for reasons of self-interest to protect capitalism. Such support should take a variety of forms, including encouraging employees to vote, collaborating with voter registration efforts in their communities and helping to ensure free and fair elections. In a world of raw, authoritarian politics, neither democracy nor capitalism will thrive.

When will capitalism’s proponents acknowledge that our economic system, and the social and political systems built around it, are in trouble? John Elkington, in his recent book “Green Swans,” answers this question by observing, “It will be when big business realizes that its long-term survival is threatened by unsustainable business practices.”

The conventional wisdom is that this year’s U.S. presidential election represents a contest between two opposing political alternatives: center-right (Trump) vs. center-left (Biden). This narrow, insider’s view ignores the fact that Americans are no longer willing to accept the glaring injustices created by an economic system in which a rising stock market and higher share prices don’t reflect the realities of daily life or provide sufficient opportunities for social mobility irrespective of race, gender or sexual orientation.

Capitalism is also on the ballot in 2020.