The problem with your net-zero commitment

Net-zero pledges place the emphasis on numbers when the focus should be on the quality of credits. Read More

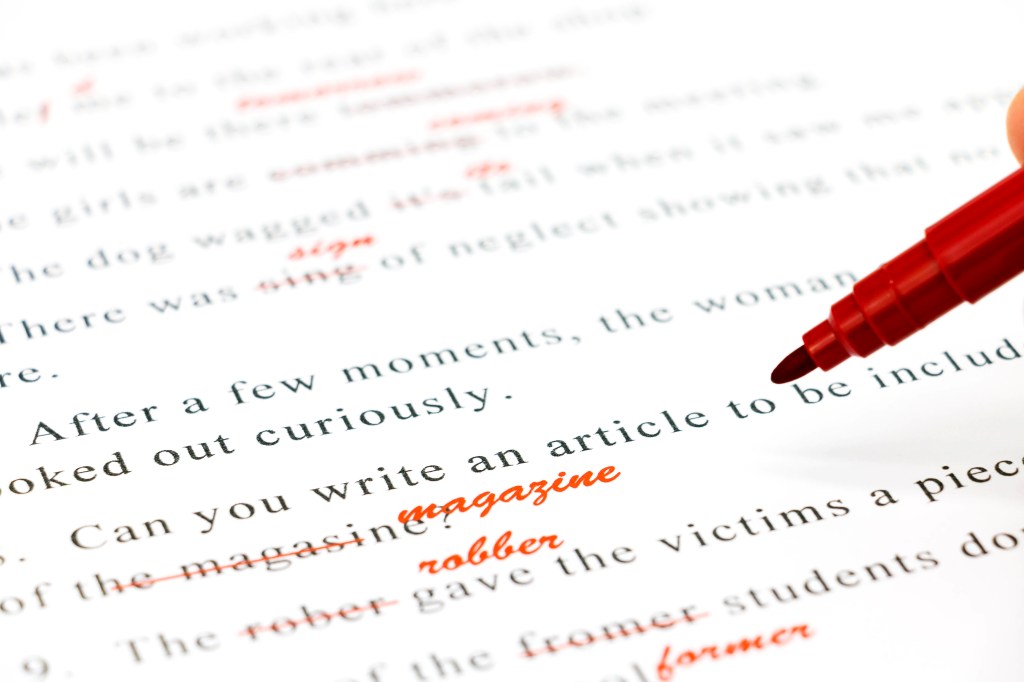

Companies may need to start redlining their net-zero commitments to focus on quality over quantity//Shutterstock

The boom of net-zero commitments has made one thing clear: The current carbon crediting system is on the cusp of taking off. That’s not necessarily good news.

Net-zero commitments from corporations, governments and other organizations have doubled in less than a year. As of this writing, the World Green Building Council has signed 94 business, 28 cities and six states to commit to making their own buildings net-zero by 2030, and advocate for all buildings to operate at net zero by 2050. Some of the biggest companies in the world including Amazon, Shell and Ford; airlines, including JetBlue and United; and construction firms such as Mace Group have committed to going carbon-neutral or even negative over the next few decades.

Companies will approach their net-zero commitments in a variety of ways: through renewable power purchases; reclaiming materials; inventing new ones; switching business models; and others. And while it is possible to make good on a net zero commitment without offsets, inevitably, many will need to turn to carbon offsets to “neutralize” whatever emissions couldn’t be eliminated through efficiencies, fuel-switching and other tactics. Vivid Economics predicts the carbon offset market to hit $1.4 trillion annually in 20 years, a roughly five-thousandfold increase from $247.9 million in 2020.

Organizations buy carbon offsets, also known as carbon credits, to counteract their emissions by paying someone else to avoid emitting greenhouse gases or to remove emissions already released into the atmosphere. It can be as simple as writing a check. But activists are concerned that the carbon offset system allows companies to forgo making significant, and sometimes costly or difficult, changes to their operations. Instead, these companies can continue operating as usual and buy all the offsets they need to seem environmentally conscious.

The reality is carbon offsets are an important tool for companies to counteract the truly unavoidable emissions and get over the finish line of their net-zero goals. But how offsets are produced and accounted for is where the problems begin.

Right now, the demand for carbon credits is starting to outpace the supply, especially for high-quality credits. To be considered a high-quality offset, a project needs to store carbon that would not have been stored without the credit and keep it sequestered for multiple centuries of years. Moreover, high-quality offsets may not push emissions into another sector or location and much improve the quality of life in the communities where the offsets are produced. For example, an urban tree-planting effort can provide shade that could decrease air conditioning emissions and heat-related medical emergencies while also sequestering carbon and improving local air quality. In most cases, higher quality leads to higher prices.

Lower-quality offsets are less expensive but sometimes don’t actually decrease emissions — and in some cases actually increase them. Low-quality credits might pay a farmer to adopt regenerative agriculture practices the farmer was already planning to embrace — not for climate reasons but because it would increase the farm’s yield. Or it might involve protecting a forest, only to increase emissions by inadvertently pushing logging into an area that isn’t using sustainable practices, or into an area that harms a local economy.

The challenge is that high-quality offsets are harder to find and assess.

Quantity vs. quality

Many times, evaluating a carbon credit means measuring something you can’t see or comparing your investment to an event that never happened. You are only able to estimate the impact, not quantitatively measure it.

“People will tell you [the voluntary market] has removed a billion tons,” said Jonathan Goldberg, CEO of Carbon Direct. “It could be zero. And my zero number is a reflection of the impossibility of calculating actual figures on things that are indecipherable.”

Net-zero commitments require that companies count the number of tons they have emitted in order to counteract them. To companies with net-zero commitments, credits are valued based on how much carbon they remove or avoid putting into the atmosphere. So the entire carbon economy has become all about quantity over quality — the number of tons removed as opposed to how well or for how long or those tons will be sequestered.

“The way a lot of these [net-zero] pledges are framed makes it all about the number of tons that need to be removed or offset,” said Jeremy Freeman, executive director of CarbonPlan. “If you’re then working under a limited budget, it’s going to push you towards trying to get as many tons as possible for as cheap as possible.”

Carbon is bought and sold through a commodity lens, where every carbon credit is of equal value, no matter what the quality. In this system, the cheapest credit that removes or avoids the most tons always will win out.

Viewing carbon as a commodity isn’t necessarily a bad thing. But commoditization requires standardization, something the carbon market is lacking.

For example, consider needing to replace a specific part in your car. According to the manual, it’s the H41 model brake pads. Imagine your frustration if you ordered the H41 pads and they don’t fit your car. Whenever you buy something, you want to know exactly what you’re getting in terms of price, quality and efficacy. And you want that to be the same each time. That’s where standards come in.

In the case of carbon offsets, the lack of standards means you don’t really know what you’re paying for. Instead, many standards, verifications and auditing systems have cropped up in the voluntary offsets market. There isn’t one set of guidelines everyone is adhering to or everyone even understands.

So in a carbon market without standardization and with a hyper-focus on quantity instead of quality, cheap credits start to win. In a world where voluntarily offsetting one’s emissions was seen as a “nice to do,” such details were less important. In today’s world, where getting to net-zero is becoming an expectation, details matter.

“There’s often a race to the bottom in quality and robustness amongst the dimensions that we care about like additionality, permanence, co-benefits to the ecosystems and communities, and avoidance of harm to those ecosystems and communities,” said Noah Deich, executive director of the nonprofit research group Carbon180. “So it’s tough. I think that is a big piece of why we don’t have good offsets.”

Cheap credits are cheap for a reason. These projects are not likely to be following the best practices for additionality, permanence and leakage. Your low-price credits actually could be putting more carbon into the atmosphere, inadvertently. Credits need to be implemented with tremendous care, a process that includes investigating the thousands of possible unintended consequences. If they aren’t, that logging company you paid not to destroy a few acres of Amazon forest could move its operations down the road and destroy an area that was supporting a rural tribe of native people.

If we are to value credits strictly on the number of tons removed or avoided, we first need standardization. We need to start looking at the projects from a harsh business perspective instead of one that makes us feel warm and fuzzy and looks impressive in a press release about your net-zero pledge.

“We should be saying, just like with any industrial project, is it working?” said Danny Cullenward, policy director of CarbonPlan. “Is it delivering what we want it to do? Is it doing it at the right cost or the right quality?”

The bottom line is that in the race to achieve carbon neutrality, companies might be funneling money into a system that is measuring all the wrong things. Instead of a net-zero framing, we need one that focuses on offset quality. Companies should budget to buy the best, highest-quality carbon removal instead of buying the most tons. Shifting the focus from quantity to quality could enable all those net-zero commitments to actually have their desired impact.

Correction: Updated World Green Building Council number of businesses signed to its 2030 commitment.