What is transition finance, and why it matters

Wall Street sees transition finance as a multitrillion-dollar opportunity for investors. Read More

Source: Shutterstock/Vylaks

At the start of the year, I predicted “transition finance” will be a top theme to follow in 2024, after it dominated sustainable finance discussions during the recent COP 28 proceedings in Dubai.

Two things are clear: Transition finance represents a multi-trillion-dollar opportunity for investors, and Wall Street already sees the case for these vehicles to provide attractive risk-adjusted returns.

Many interpretations

Transition finance refers to investments meant to decarbonize high-emitting and hard-to-abate industries such as steel, aviation and shipping. This capital is also aimed at addressing potential social impacts associated with decarbonization, including unemployment and loss of tax revenue for local governments.

For example, industrial conglomerate Mitsubishi Heavy Industries issued its first transition bond Sept. 8, 2022 to raise $71 million for corporate investments in hydrogen gas turbines, high-efficiency gas turbines fueled by liquid natural gas, and carbon capture and storage technology, among other things.

Japan Airlines was the first airline to issue transition bonds, with a $6.7 million issue in March 2022 and a second for the same amount 15 months later. Proceeds from both bonds will go towards upgrading the airline’s fleet to fuel-efficient aircraft.

One significant barrier to scaling transition finance is a lack of a standard framework and taxonomy for discussions, decision-making and documentation. An RMI analysis of 17 transition finance frameworks found 17 definitions. The common theme was a focus on “the decarbonization of high-emitting entities and/or hard-to-abate sectors.”

Here are three high-profile examples:

- Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero: Financial Institution Net-zero Transition Plans

- Climate Bonds Initiative: Financing Credible Transitions

- Standard Chartered: Transition Finance Framework 2023

Private capital has entered the chat

The private sector and investment community has seen the opportunity sustainability-related finance presents. There was $2.74 trillion in funds that claim to focus on sustainability, impact or ESG factors as of September, according to Morningstar, and it looks like Wall Street has its eyes set on transition finance as its next trillion-dollar opportunity.

Private equity giants Apollo and Brookfield have both launched multi-billion dollar transition funds and are aiming for $100 billion and $200 billion for their respective clean energy and climate capital platforms.

KKR is looking to raise $7 billion for its first global climate fund that will invest in both green technologies and in decarbonizing existing assets such as infrastructure.

The world’s largest asset manager and the one most associated with ESG investing in the United States, BlackRock, already has a $100 billion transition-investing platform.

Banks are getting in on transition finance, too. Barclays is setting up an energy transition group to advise energy and power clients on their energy transition strategies, and it is aiming to facilitate $1 trillion in transition financing by the end of 2030. Citi created a similar group in 2021.

A linchpin: Public-private partnerships

Financing the transition to a net-zero emissions economy will require unprecedented sums of money that no individual entity is able to fund itself. For transition finance to work, governments and investors will need to pool their capital in new ways.

The United Arab Emirates’ climate finance fund announced at COP28 last year is one model for how public-private partnerships could mobilize capital to finance the transition to a net-zero economy. The country’s $30 billion commitment includes $5 billion designated for projects in the Global South. The UAE will cap its returns for that portion of the fund at 5 percent. Any returns above that threshold will be redistributed to the other investors as part of a derisking clause intended to attract private capital to co-invest in these projects.

By limiting its own returns to 5 percent, the UAE is making the fund a much more attractive opportunity for private investors who will receive UAE’s returns over 5 percent, Bloomberg reported. Under this structure, investors could see their returns increase by as much as half a percent.

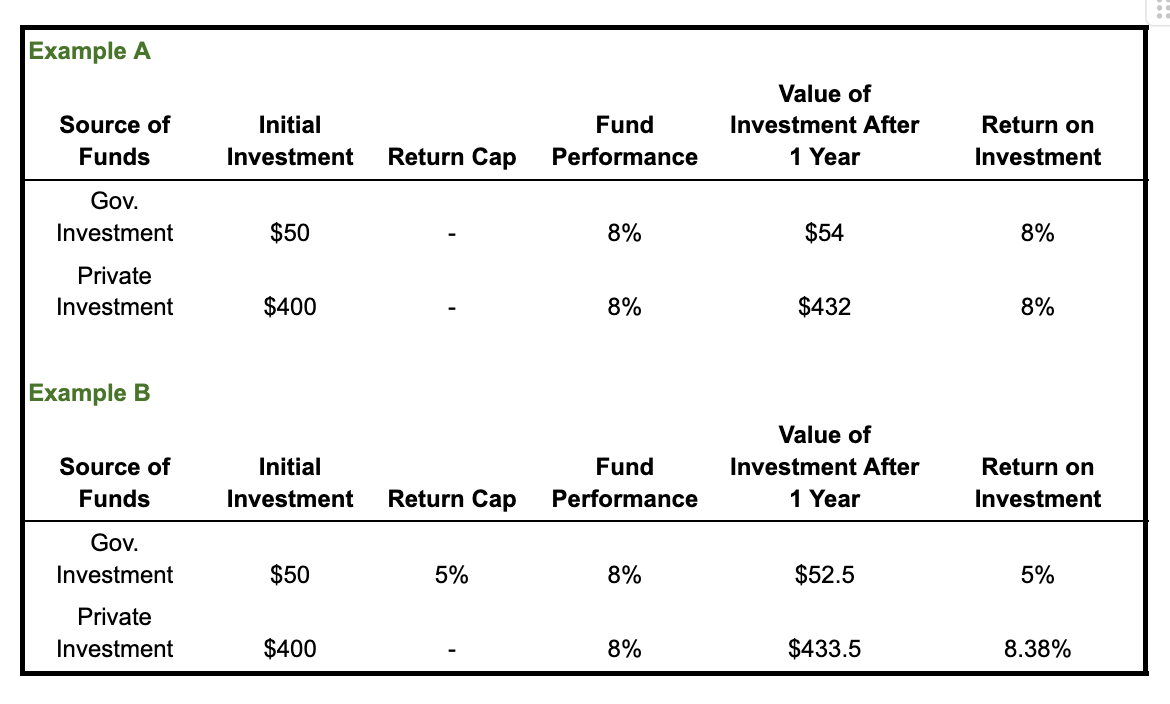

Let’s say the fund invested $50 of government money alongside $400 of private capital. The chart below shows two versions of a scenario in which the fund returns 8 percent on investments. Example A depicts the returns allocated to each investor group without any caps on returns. Example B shows what would happen if the returns of the government’s investment are capped at 5 percent. In short: If the investment had an 8 percent return in its first year, the private investors in Example B would see their return on investment increase by 38 basis points.

The UAE hopes that its capped returns will help attract private capital and grow the fund to $250 billion by 2050.

However, this is just a drop in the bucket of what will be needed to transition the global economy. For example, the Climate Bonds Initiative estimates that China’s steel industry will require $3.14 trillion to achieve carbon neutrality.

You can expect to hear more about transition finance throughout the year as GFANZ anticipates more than 250 financial institutions will publish transition plans using its framework in 2024.