What’s next for Fannie Mae’s 12-year $120 billion quest for green housing

It's the largest issuer of green bonds, but only a small portion of the homes it finances meet environmental standards. Read More

Fannie Mae has been working to reduce the climate impact of housing in the U.S. since 2011. That’s a big task, as energy use by homes accounts for 19 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions; home construction and water use have even more impact. And the reach of Fannie Mae, officially the Federal National Mortgage Association, is vast. The privately owned company, created by Congress in 1938, provides the funding for more than 25 percent of the home loans in the United States.

Fannie Mae’s green programs are also big. Last year, the company provided $8.9 billion in financing to support more climate-efficient housing. But that represented only 2.4 percent of the company’s $371 billion volume.

To understand the company’s challenges as it tries to reduce the carbon footprint of the housing it finances, GreenBiz spoke with Laurel Davis, Fannie Mae’s senior vice president for ESG and Mission.

“Ultimately, our $4 trillion portfolio is all about making sure people have a roof over their head that is high-quality and accessible,” said Davis. “There’s a whole lot wrapped up in that mission. One part is helping people transition to a low-carbon future.”

The plan

At the outset, Fannie Mae identified an area where it could have a significant climate impact quickly: improving existing apartment buildings and other multifamily housing complexes. Landlords who agree to invest in reducing energy and water use can receive lower interest rates and higher borrowing limits.

Fannie Mae is a middleman. It buys loans by banks and other local lenders, then packages them into mortgage-backed bonds and sells them to investors. In 2012, it started bundling the loans made through the green refinancing program into “green bonds” intended to appeal to environmentally conscious investors.

In 2015, it started offering discounted financing for new construction that conforms to green building standards, first for multifamily buildings and in 2020 for single-family homes. The discounts increase based on the expected energy savings. The top tier, “Towards Zero,” requires a 50 percent reduction in energy use. Most of the buildings in the program, however, use less stringent standards.

The challenges

Fannie Mae has found it hard to increase participation in its green initiatives beyond a small fraction of its overall business. Each loan needs to achieve a delicate balance: offering a good deal for borrowers, providing an adequate return for investors and meeting the company’s government-mandated objectives. Davis highlighted three factors that make achieving that balance especially difficult:

1. Aging single-family housing stock

Fannie Mae has been stymied by the expense and complexity of improving the energy efficiency of single-family homes. The biggest impact comes from building new homes to modern standards, but housing construction is far behind the country’s needs. That leaves 82 million existing single-family homes, half of which were built before 1980, that are costly to renovate.

“How do you get a homeowner to want to electrify, for example, when the economics may not make sense for them?” Davis said. “That’s our toughest challenge and one that honestly we can’t necessarily solve.”

2. The expense of renovating multifamily projects

The economics with multifamily buildings are better, and it’s easier for Fannie Mae to deal with a larger project. Nonetheless, landlords often find the interest rate break provided by Fannie Mae (typically 0.1 percentage points) too small to cover the cost of green renovations, even after energy savings and potential rent increases. Last year, only 14 percent of the multifamily loans that Fannie Mae financed were in its green program.

To boost that number, Davis is hopeful that it can structure deals with money from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, a $27 billion creation of the Inflation Reduction Act. “Public money can improve the economics of projects that were hard to finance,” she said.

3. Competing priorities

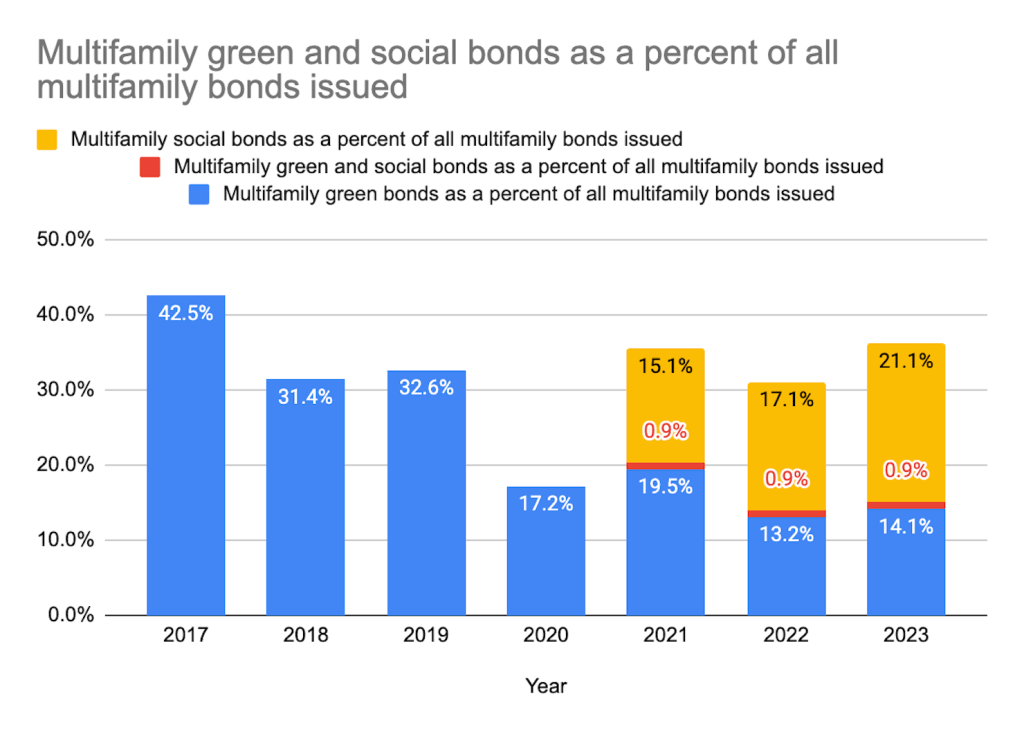

In 2021, Fannie Mae started offering impact-oriented investors a new type of bond that funds housing in low-income and disadvantaged areas. By the next year, these “Social Bonds” were outselling the green bonds, in part because they have some attractive financial characteristics in a high-interest rate environment.

So far, only 5 percent of the multifamily projects funded by Fannie Mae’s social bonds have also met its green standards.

“The biggest challenge we face is how to bring the green and social pieces together,” Davis said.

The results

Since 2012, Fannie Mae has issued more than $120 billion in green bonds, making it the largest issuer of these securities in the United States. In 2023, Fannie Mae’s multifamily bond program raised $7.5 billion to support the renovation or building of 48,000 apartments. It raised $1.4 billion that backed the construction of 4,000 single-family homes.

There’s another gauge beyond simply the amount of green funding it provides: How much are the projects it finances actually contributing to fighting climate change? Fannie Mae’s initial program allowed borrowers to qualify for green loans if they committed to a 30% improvement in any combination of water or energy use, and most of the initial projects only involved water savings. In 2019, Fannie Mae tightened the rules to require at least a 15% reduction in energy consumption.

Still, Fannie Mae’s green programs are targeted at improving the energy efficiency of the nation’s housing rather than meeting global targets for greenhouse gas reduction. Fannie Mae’s green bond programs were characterized as “Light Green” — the middle of a five-point scale from red to dark green — by Shades of Green, an Oslo-based research organization now owned by S&P Global.

The reviewers criticized several gaps in the Fannie Mae standards: They don’t directly account for the climate impact of new construction; they don’t look at how the locations of new buildings contribute to transportation-driven energy use; and they permit projects that use fossil fuels to provide heat and hot water.

All of those elements cost money. And making housing more expensive, as Davis describes it, undercuts Fannie Mae’s mission.

“Our core social issue is housing stability,” Davis said. “If you put people into homes that they can’t afford to stay in, you’ve made the problem worse.”

[Supercharge your impact alongside other visionaries, experts and innovators leading the way to a regenerative future at VERGE 24, Oct. 29-31, San Jose.]