What’s wrong with burning garbage?

Using waste seems like a good thing. But relying on waste so we can use it is problematic. Read More

Something doesn’t sit right with me about burning garbage for energy.

Instinctively, it seems that if we are burning garbage, something has gone horribly wrong in the value chain. It’s a dirty solution to a dirty problem and irreparably removes any remaining value from materials.

Yet garbage incineration to create energy — a process sometimes called waste-to-energy — is actually pretty prevalent in the United States.

How common is garbage incineration?

There are 72 operating incinerators in 24 U.S. states that generated around 14 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity in 2018 – or about enough electricity to power 1.3 million homes for a year.

The U.S. Energy Information Agency says about 13 percent of the country’s solid waste is burned for energy, while over half ends up in the landfill and about a third is recycled or composted. (These figures are based on 2017 numbers, before China officially declared recycling broken.)

How culpable are companies in the waste problem?

Businesses create a lot of trash. According to a study conducted by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, for every $1 million in revenue, the largest publicly traded companies in the U.S. generate 7.81 metric tons of waste. That amounted to 342 million metric tons in 2014 alone.

Here’s the thing: Much of this waste is avoidable. While only a third of solid waste is diverted, that number could be as high as 80 percent with ambitious recycling and composting programs (San Francisco already has reached a 80 percent diversion rate).

A handful of large corporations — from Subaru to Microsoft — have adopted “zero waste” goals. This isn’t altruistic: Wasting less is cheaper, and diverting materials can become a resource.

If companies were to tackle this seriously, it would make a significant amount of garbage in this country and create industries and markets for municipalities and communities to follow suit.

The phrase “dumpster fire” is actually an apt description of our literal practice of burning garbage. It’s disastrous and mishandled. Here’s why:

1. We are relying on something we want less of

Using waste seems like a good thing. But relying on waste so we can use it is problematic.

Imagine this: A city invests $1 billion on a trash incinerator. Now if it reduces solid waste (a good thing), it will have a stranded asset (a bad thing). Suddenly, incinerators are misaligning incentives and competing against zero-waste goals.

Sweden is running into this problem. The Scandinavian country boasts that less than 1 percent of household waste ends up in the landfill. Waste that isn’t recycled is incinerated and used to provide heat to thousands of residents. But as the country has decreased waste, Sweden imports trash from Britain and Norway to meet the needs of its 34 “waste-to-energy” plants. Its system is relying on trash we would prefer to not need.

2. Burning may not be garbage’s highest use

Burning garbage that could be recycled or composted is a waste of energy. Three to five times more energy can be saved through reuse, recycling and composting than can be created through incineration, according to the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives.

The investment in expensive incineration equipment could encourage burning waste that would have more value if the natural capital went into new products.

For example, Western Australia is considering a garbage incinerator program as an energy source that will address its recycling crisis (China stopped taking Australia’s plastics, too). Advocates of zero waste warn that such an investment would incentivize the region to burn materials that could be recycled or composted.

3. Confusing burning garbage with renewable energy

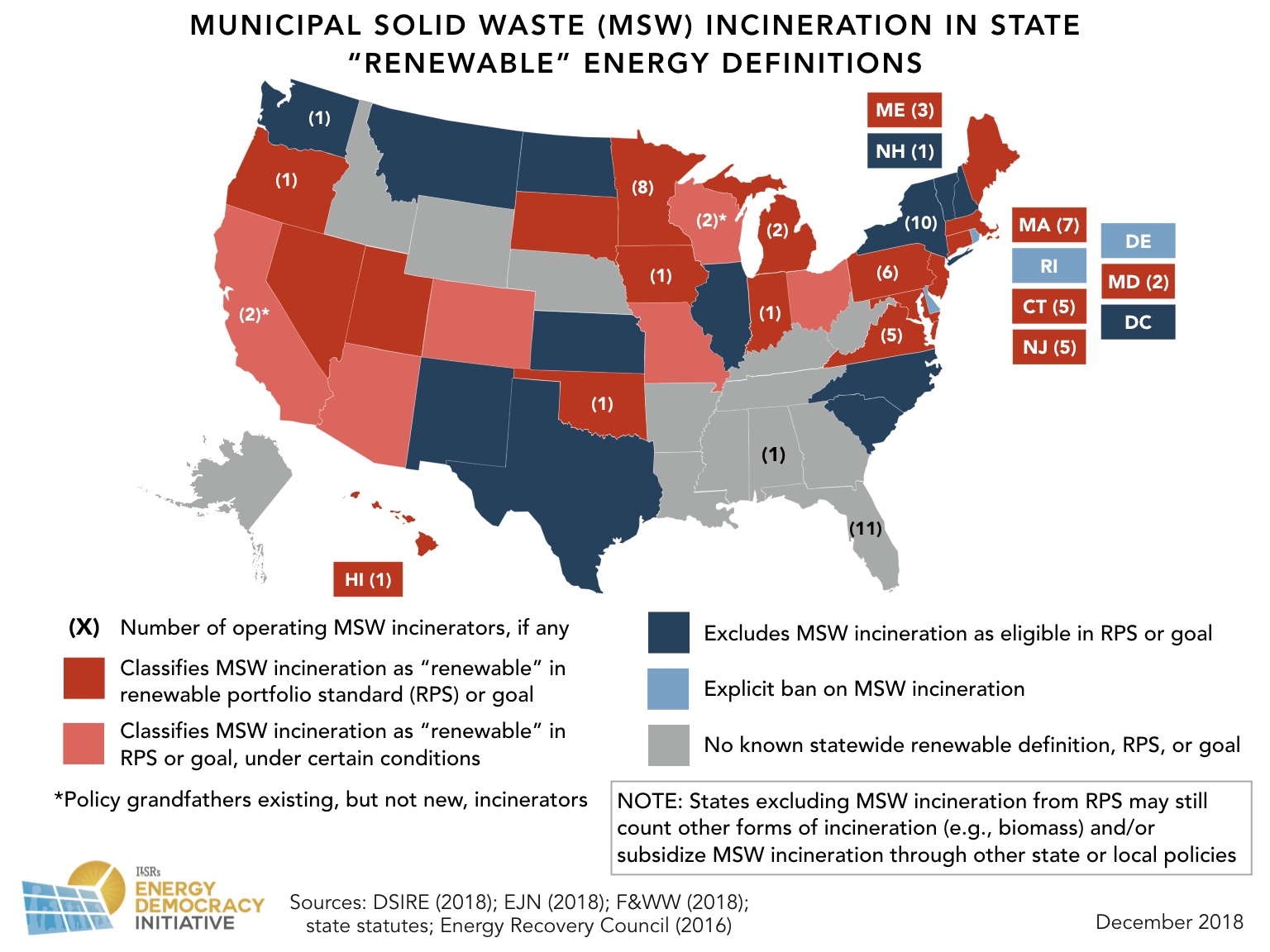

Today, 23 states (including Oregon, New Jersey and Hawaii) consider burning solid waste to be a source of “renewable” energy. That allows burning garbage to be counted towards states’ Renewable Portfolio Standards and qualify for renewable energy subsidies.

My opinion: 23 states got this wrong. Renewable energy is an energy source that is not depleted as used. What is renewable about burning trash piles, especially as we work to reduce the waste across the board?

4. Incinerators disproportionately impact marginalized communities

Living close to incinerators exposes nearby communities to high levels of pollution. In textbook environmental racism fashion, those neighborhoods are disproportionately low-income communities and communities of color.

This has led to grassroots efforts to fight incineration in communities across the country — from Baltimore to Camden, New Jersey, and Hartford, Connecticut.

Where to go from here?

First and foremost, companies and communities need to reduce waste and divert more garbage. That by itself would get us at least 70 percent of the way to a solution.

But while we’re transitioning away from single-use packaging and linear waste habits, what is the best solution for garbage?

One option: Invest in new, better technologies. Cox Enterprise is taking this strategy, investing in two startups: Sierra Energy and Nexus Fuels. Sierra Energy has a prototype for a gasification technology that it says doesn’t create harmful air pollution. The company has raised $33 million to see if it can scale.

Nexus Fuels is working to divert landfill- and ocean-bound plastics to convert them into chemicals and fuel, a process known as molecular, or chemical, recycling. The Atlanta-based company recently signed a deal with a Shell chemical plant to synthesize chemicals for other industrial uses.

Another option: Use that capital and energy to create the infrastructure and partnerships needed to truly reach zero-waste goals. The concern is that investment in new technologies will require a waste stream for investors to make a profit. That could disincentivize the move to zero waste.

Additionally, a search for better waste-to-energy technologies hasn’t worked to date. Analysis by the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives shows that companies have spent 30 years and $2 billion trying to reach gasification and pyrolysis to no avail. The research details how these incineration alternatives historically have missed their energy generation and pollution targets.

This one debate mirrors so many in the environmental and sustainability community: Do we prioritize changing harmful behaviors or creating technological solutions so our behaviors are less harmful?

This article is adapted from GreenBiz’s newsletter Energy Weekly, running Thursdays. Subscribe here.