Why efforts to curb plastic waste are failing

The global burden of plastic waste continues to escalate even to the point of requiring a redefinition of its sources and scale. Read More

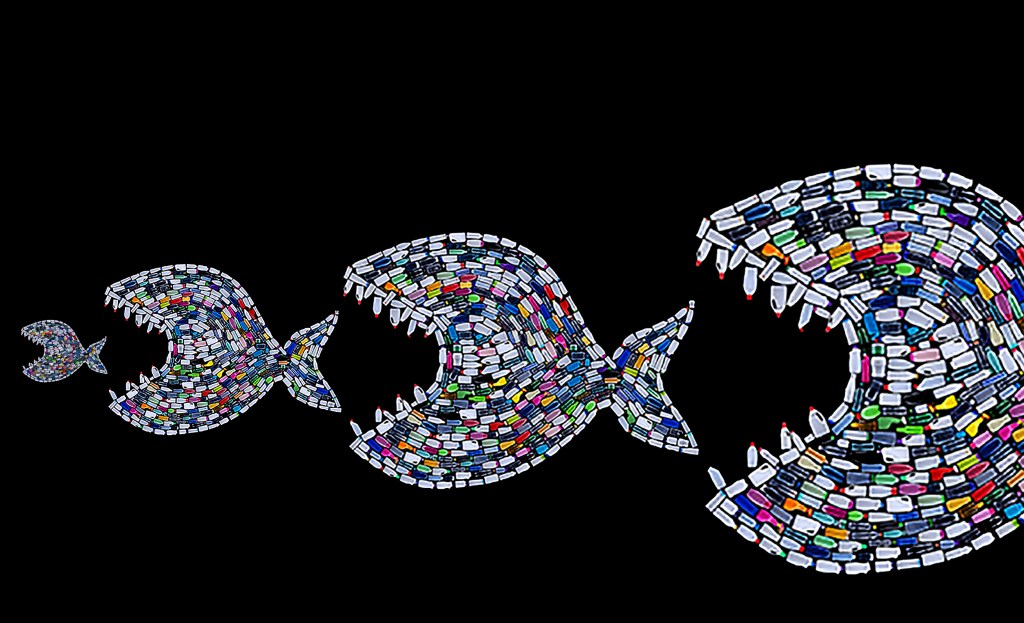

GreenBiz photocollage via Shutterstock

The COVID-19 pandemic, economic decline, inequality and race relations, and climate change have collectively moved the growing plastic waste crisis out of the priority inbox. To a degree, this is the inevitable consequence of limited political bandwidth to address multiple crises. Beyond the political realm, there are deep fault lines in how businesses, governments and non-government organizations have conceptualized and organized plastic waste solutions.

The global burden of plastic waste continues to escalate even to the point of requiring a redefinition of its sources and scale. Consider these facts:

- Escalating plastic waste volumes. More than 8.3 billion tons of plastic waste have been generated, and most of this amount has been discarded. If present trends continue, in excess of 12 billion tons will be disposed of in landfills or the natural environment by 2050. According to a 2020 study by The Pew Charitable Trusts and SYSTEMIQ, annual plastic flows to the ocean can be expected to rise to 29 million metric tons in 2040, compared to 11 million metric tons in 2016.

- New waste categories. New sources of plastic waste continue to emerge and present new global challenges to public safety. During the pandemic, single-use plastic has grown through the use of personal protective equipment, medical devices, packaging for improved safety and for expanded food delivery services. These plastics have limited recycling potential and are frequently contaminated.

- Global, not regional in scale. The United Nations has concluded that more than half of the plastic waste in oceans can be attributed to the lack of sufficient waste collection and management systems in South East Asian nations such as China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam (with an increasing focus upon India). However, the United States exports about half of its recyclable waste due to insufficient infrastructure to manage domestic demand. Of the total amount exported, about 88 percent went to nations with inadequate waste management systems. Meanwhile, African nations such as Egypt and Morocco are increasingly prominent as plastic waste sources.

- Incremental government actions. As of Jan. 1, nonhazardous plastic waste subject to the Basel Convention’s controls and trade bans was expanded. The European Union has gone one step further than the Basel requirements by banning the export of difficult to recycle plastic waste outside OECD countries. The United States has not ratified the Basel regime, and plastic waste shipments to or from America are prohibited. The Biden administration has given no early signal of its thinking on plastic waste.

- Compartmentalized solutions. Numerous efforts are underway that can contribute to plastic waste solutions. They include: Circulate Capital’s Ocean Fund has announced an investment of $39 million to capitalize India’s recycling value chain; the chemical industry’s Alliance to End Plastic Waste launched eight projects in nine countries in 2020; and major consumer brands are shifting away from the manufacture of virgin materials and towards recycled feedstocks. These and other initiatives will achieve some progress. Unfortunately, they all address only compartmentalized aspects of an expanding crisis with limited financing and, if successful, will require many years to reach market scale.

What isn’t working?

Four major structural factors impede solutions at scale for the global plastic waste crisis. They include:

- Conception of the plastics waste problem. Many well-intentioned initiatives focus on single solutions — material design, source reduction, plastics reuse, financing waste management infrastructure, recycling, regulatory policy and disposal credits and fees, to name a few — rather than taking a systems approach that identifies all major leverage points through the plastics life cycle and value chain. Until an integrated systems approach is implemented, with agreement among the principal institutional actors (including consumers), the plastic waste crisis increasingly will overwhelm oceans and other natural systems and further debilitate planetary habitability.

- Business model mantra. The expansion in plastics production is attributable to a business model based upon three pillars: lower-cost petroleum and natural gas commodities that provide the principal manufacturing raw materials; growing demand for packaging and other plastics products across markets sectors and geographic regions; and a business and consumer philosophy dominated by single use and disposal without accounting for environmental and social costs. The global economy is entering into a hyper-phase of plastics production as petroleum companies seek to adjust to declining markets in electricity generation and transportation fuels and convert to increasingly larger petrochemical production to service a chemicals market expected to grow from 16 percent of oil demand in 2020 to 20 percent by 2040. Tens of billions of dollars in new capital investment resulting in ever-larger refineries and chemical plants are in the pipeline in Saudi Arabia, Singapore and Texas to satisfy this demand.

- Multiple agendas and competing narratives. The cacophony of overlapping and, at times, conflicting agendas — among think tanks, foundations, academicians, NGOs, the private sector and multiple government institutions — greatly complicate the development of a collective commitment to change the incentives and rules for plastics production, consumption and waste management.

- Deterioration in geopolitical collaboration. In contrast to the successful negotiation of the 2015 Paris Climate Accord — a high-water mark in 21st-century diplomacy — international relations today among the major political blocs (China, the EU and the United States) are characterized by more nationalistic trade policies, decreased reliance upon established mechanisms for resolving disputes (the World Trade Organization, G-20 summits), and a decline of transparency and trust among political leaders. It is unlikely that in the short-term (three to five years) the world’s most influential leaders can focus on plastic waste and reach a comprehensive accord committing to global scale solutions.

What, then, is to be done?

Building effective solutions

Success in reversing the rising tide of plastic waste will result less from technical solutions and more from novel institutional designs, economic incentives and investments, and policy frameworks operating through innovative governance mechanisms at global scale. The dimensions of this success depend on recognizing and taking action on four interdependent issues. They include:

- The plastic waste crisis is a growing part of the climate change crisis. The plastics industry is the second-largest and fastest-growing source of industrial greenhouse gases. Today, about 4-8 percent of annual global oil consumption is used in making plastics, an amount that will increase to 20 percent by 2050 according to the World Economic Forum. It is time that the value chain of plastics production, consumption and disposal/reuse be added as a priority emissions reduction sector by national and international legal authorities.

- Focus on systems, not individual solutions. Given the rates of plastics production and consumption, it is already evident that source reduction, recycling or regulatory policy alone cannot solve the plastic waste crisis. Different solutions will need to be tailored to variable waste composition, available economic and policy instruments and consumer behavior across the globe. The Pew/SYSTEMIQ report, “Breaking the Plastic Wave,” offers a number of complementary proposals for building a comprehensive system for plastic waste management, including: reducing growth in plastic production and consumption; substituting paper and other materials for plastic where value is added; designing products and packaging for recycling; expanding waste collection rates in middle-/lower-income nations; building disposal facilities as a transitional measure; and reducing plastic waste exports.

- Apply a full array of economic investments and policy instruments. The range of available options will vary considerably by nation or region, but they should coalesce around several fundamental outcomes: removing the cost advantage of virgin materials over recycled materials; establishing higher product certification and regulatory standards for plastic design criteria, materials, recyclability and reuse; and mobilizing investment capital and the power of state financing to underwrite precommercial innovations in technology and materials (similar to expedited development of commercial COVID-19 vaccines).

- Practice innovative governance. An appetite exists among some policy experts and stakeholders to establish a new international agreement to prevent pollution from plastic waste. Such a proposal requires many years to develop and would unleash intensive lobbying by business, government and NGO actors to tilt the angle and size of the negotiating table in their favor.

An alternative approach, borrowed from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, would create joint governance across nations and regions. This proposed Global Commitment to Reduce Plastic Waste would operate through a board of directors that includes representatives from relevant nations and communities, NGOs, foundations, the private sector and other knowledgeable regional representatives into a global partnership. Funding would be raised through government, private sector, foundation and other contributions.

The Global Commitment would disburse grants for a variety of outcomes, including analysis of waste streams, infrastructure development, technological and management innovations, and other priorities all aimed at achieving reductions in plastic waste volumes and risks through system-based solutions. Full transparency would be practiced in goal setting, financial management and performance outcomes at all levels of the Global Commitment.

The plastic waste crisis is growing, and time is getting shorter to mobilize an effective response. Efforts to date, while yielding insights and incremental progress, have not developed solutions at the scale at which the crisis exists. More creativity and bolder imagination — channeled through a system of multi-layered interventions — represent the most promising strategy for confronting this runaway failure of our modern way of life.