Why Renewcell failed

H&M and Levi’s wanted the company’s revolutionary recycled cotton product — but the industry couldn’t handle it. Read More

Inside a Renewcell plant. Credit: Renewcell

This time last year, Renewcell CEO Patrik Lundström appeared to have everything he needed to end the fashion industry’s dependence on emissions-heavy virgin cotton and replace it with Circulose, his company’s sustainable alternative made from recycled clothing:

- The company had $29 million in financing from H&M over seven years to get production off the ground.

- The product itself was “world changing,” and looked and felt great, according to those who worked with it.

- Renewcell had the clients: H&M, Tommy Hilfiger parent PVH and Zara parent Inditex each agreed to buy the product in multi-year “offtake” agreements. Levi’s launched its Circular 501 model jeans in 2022 with Circulose.

- The company’s factory in Sundsvall, 235 miles north of Stockholm, had a production capacity of 10,000 metric tons per month.

And the stock market agreed. In September, Renewcell’s stock hit a high for the year of about $9 per share.

But by February, Renewcell had fired Lundström. The company lost its financing and filed for bankruptcy. The stock now sits about 50 cents, having lost 95 percent of its value.

Main reasons for the collapse

Partners, analysts and employees are still sifting through the wreckage to figure out what went wrong. There were multiple factors, of course. But sources who spoke to GreenBiz cited three major reasons for the collapse:

- Basic economics: Circulose cost twice as much as alternative materials, and many textile factories operate on thin margins.

- The fashion industry’s “take, make, waste” mindset. A lot of companies say they want to make their manufacturing more sustainable but many don’t have the patience for it.

- The fashion industry is hidebound by traditional processes which have been based on virgin cotton for hundreds of years. Renewcell was unable to persuade global supply chains to retool in favor of its product.

When the end came, Renewcell’s chairman of the board, Michael Berg, blamed everybody else: “This is a sad day for the environment, our employees, our shareholders, and our other stakeholders, and it is a testament to the lack of leadership and necessary pace of change in the fashion industry,” he said in a statement.

Circulose was too expensive

Renewcell’s Circulose was based on a great theory: Most discarded garments end up in landfills. Instead of throwing old clothes away, why not recycle them into new material, for new clothes?

Renewcell’s 100-worker plant is in a retrofitted paper mill, which used hydropower from a nearby river. The company said it could produce 120,000 metric tons of cellulose pulp a year. Inside, the company chemically recycled cast-off garments and cotton scraps, cleaning and processing them into a slurry that dried into sheets of Circulose. Fiber makers use those sheets to make rayons, such as viscose, and supply the retail brands.

But the final product — Circulose pulp — cost nearly twice as much as competing wood pulp. Plus, fiber producers’ prices for their Renewcell-based viscose were 50 percent higher than regular viscose.

A dress in the H&M Conscious Collection that uses Renewcell’s Circulose. Credit: H&M/Alexander Donka

Fiber makes up only 3 to 5 percent of the retail price of a dress or pair of pants, according to Renewcell’s chief commercial officer, Tricia Carey. “That doesn’t mean that your garment has to be double [in price], or your garment even has to be 40 percent more … you’re looking at pennies, that’s it.”

And the cost would have declined eventually, Carey insisted. For example, upcoming European Union regulations around ecological design and extended producer responsibility may make sustainable materials more attractive, if not essential, for apparel businesses to meet their sustainability targets.

In her view, the industry’s culture of speed and profit made it unable to invest a temporary premium to support a sustainable innovation.

Still, “I think we ran into basic economics to some extent on that,” said Richard Wielechowski, a senior investment analyst at Planet Tracker. He questioned whether Renewcell answered a market need in the first place. Were brands actually demanding a higher-price, lower-impact alternative to virgin cotton or wood pulp before Renewcell came along?

The answer from the market was largely “no.”

Renewcell signed up scores of brands to experiment with its product, but for experimental capsule collections only. Only a handful converted into customers who wanted Circulose in their store lines.

Management stumbles

It wasn’t just the market. Renewcell had internal problems too.

In October, its board axed CEO Lundström less than two weeks after he sold off shares in the company before a gloomy earnings call. The stock went into freefall.

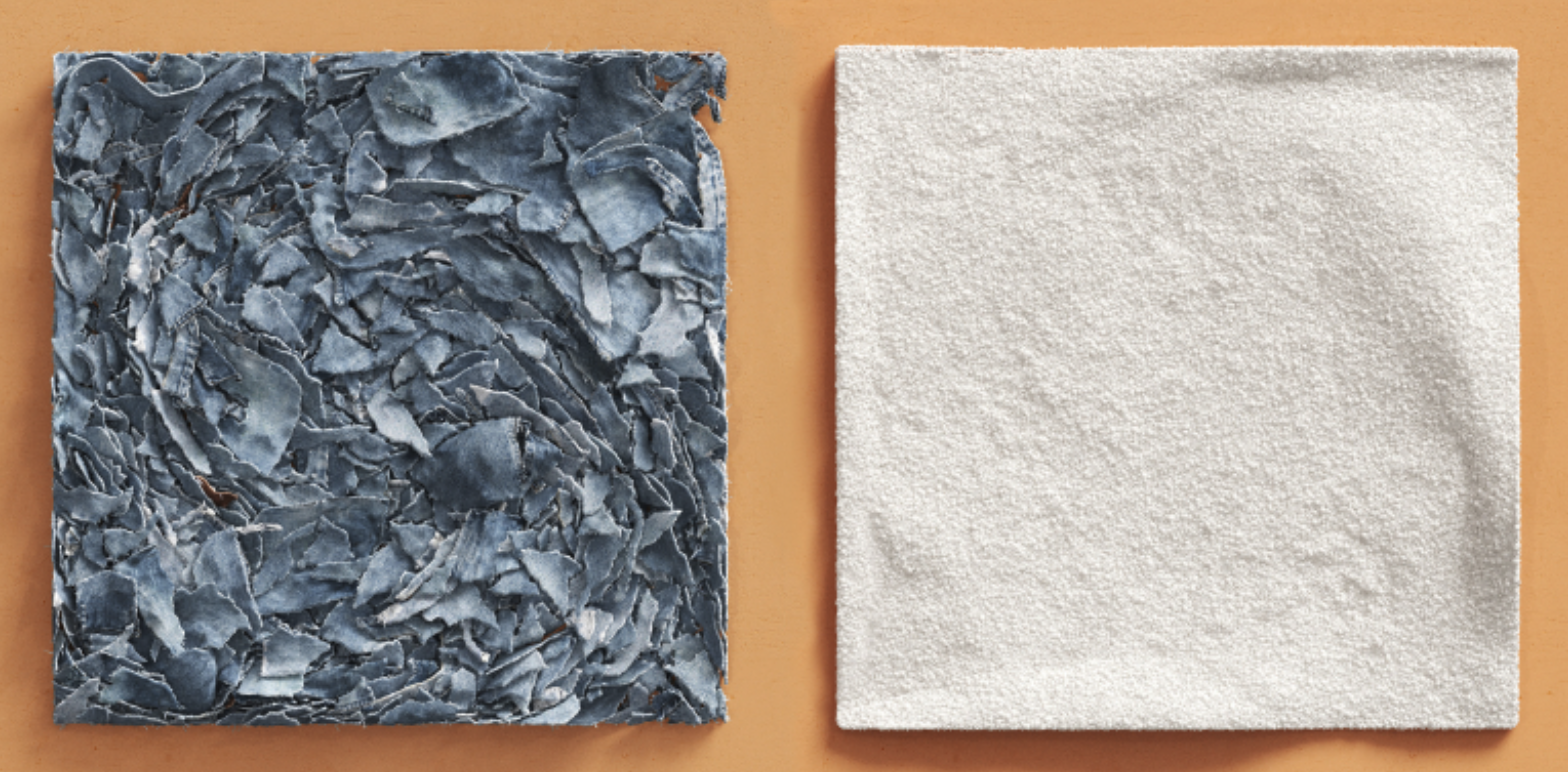

Shredded denim next to Circulose pulp. Credit: Renewcell

Sales were no better. The company ramped up production to 2,800 metric tons in July but deliveries fell to zero — none at all — in November.

H&M Group offered a $4.4 million short-term loan to rescue the company in December. BNP Paribas and others provided an equivalent amount in credit. But it wasn’t enough. At the beginning of 2024, H&M’s patience had run out. It abruptly terminated seven years of support.

Ten days after Renewcell’s bankruptcy, H&M moved on to another Swedish textile-to-textile venture: It co-launched recycled-polyester startup Syre with a $600 million purchasing agreement.

Why no sales?

The company appeared to be working out production efficiencies when it should have been securing customers, according to Lux research analyst Tiffany Hua, who has followed Renewcell for several years.

Inside the Sundsvall mill, production numbers showed a growing gap between output of prime pulp and lesser-quality pulp. The company wasn’t producing enough high-quality pulp for its Circulose product, in other words.

Whatever the reason, by the time Renewcell ramped up production again in December, it was too late.

It is difficult to build a supply chain from scratch

In the traditional cotton industry, growers plant the seeds and nourish the crop. After harvesting, the cotton gets cleaned and fluffed before it reaches a fiber-making operation, often in Asia. This involves processes, organizations and relationships that may have continued for decades, if not generations.

Renewcell — purchasing used cotton garments and scrap in bulk — didn’t involve any of those players. Instead, it tried to build a new supply chain from scratch, according to Carey.

In addition to worn clothing, the company also used pre-consumer discards from factories mostly in Turkey and Bangladesh, with a little from Central America and Africa. That’s a lot of shipping to and from Sweden. Fiber producers and weavers needed to learn how to transform raw sheets of Circulose pulp into fiber and fabric to sell to their brands.

“You’ve got now new players involved — collectors, sorters, pre-processors,” Carey said. “Going from linear to circular is not just taking the same players and putting them in [a new] room.”

“Being the first to market is always difficult,” Karla Magruder, founder of Accelerating Circularity, a nonprofit collaborator with Renewcell, said via email. “Typically new materials are not drop-ins to existing supply chains.”

And the company was doing it all from a converted paper mill — it wasn’t custom-built for the company’s own product.

“They were trying to reinvent the use of a new supply chain,” said Eddie Ingle, CEO of Unifi, which since 2011 has marketed a textile-to-textile polyester fiber.

Everyone wanted it, and no one wanted it

Ultimately, while the big brands were excited about having a circular, sustainable material for their fashions, the complexities proved insurmountable.

Renewcell’s “supplier network” — the fiber and textile producers it sold its product to — grew to include 116 companies by October. But actual orders were slow to materialize.

Renewcell pulp, used to create fiber blends for fabrics such as viscose. Credit: Renewcell

“It feels like they had a product that was great when they took it around conferences in the Global North and fashion weeks, and then it didn’t really sell to the fiber manufacturers who were on the ground in China, India or Bangladesh,” Planet Tracker’s Wielechowski said, describing a chicken-and-egg situation.

“You need to have the orders to really get the test planned out and do it at scale. And you only can do it at scale when you’ve got the orders.”

Ironically, none of the retail brands who agreed to use it had changed their minds. The company says it is trying to honor those agreements. Renewcell is still sitting on a two-year supply of Circulose, Carey said.

Editor’s note: After this story was published, Tricia Carey of Renewcell responded: “Renewcell just started with the commercial launch of Circulose in July 2023 and did not have the time to reach any economy of scale in the market when it usually takes 12 to 18 months to develop products. Textile circularity takes time to meet the expectations of the market to have the systemic change needed. Brands are interested in textile circularity, but moving too slowly to impact the change needed.”