Why we’re not creating the Patagonias of tomorrow

And what needs to change to create the next generation of culture-shifting regenerative companies. Read More

Speak to anyone at an impact investment conference, and you’ll find many topics of debate. However, almost everyone in the room can agree about one thing.

To the question: “Who are the figureheads of the environmental movement that you look to for leadership?” most respondents will name “Patagonia” without hesitation. I agree with them.

Patagonia is a global apparel brand with roughly $1 billion in annual revenue and considerable environmental street cred. The company and its leadership are perceived as parental figures of the Certified B Corporation movement and to the new strain of regenerative environmentalism.

The individuals holding the $114 billion purse strings of “impact money” broadly share this view. However — and ironically —if Patagonia were starting up today and looking for financing, it would never receive funding from this group. And if it did, it wouldn’t become Patagonia as we know it, but something far less significant.

That’s concerning, because it means we are potentially missing out on the Patagonias of tomorrow.

Why is that? And what can we do to change it?

Patagonia’s Footprint Chronicles provides insight into the company’s complex supply chain.

Educate and lead

First off, it’s worth ironing out some misperceptions a lot of people have about what Patagonia is and isn’t. In many ways, it is a 20th-century corporation. Patagonia outsources manufacturing of its clothing to contractors, primarily in Asia. It uses a variety of materials — not just organic cotton — which include petroleum derivatives. It is a for-profit company and far from perfect.

The big distinction is that Patagonia has been a pioneer of supply chain transparency, educating consumers on the reality of its business and the hard choices that need to be made and openly admitting when it falls short. In doing so, Patagonia has created a measuring stick that other companies need to compare themselves against, which creates a rising tide.

And regarding not being perfect: As they say, “nobody’s perfect” — the key thing is to keep striving to do better.

Since 1985, Patagonia has donated $89 million to environmental work. That’s not a bad score, and when you combine it with all the company’s non-cash environmental activity, such as the nearly 3 million public comments regarding the importance of public lands, you easily can start to imagine how this might have had a systemic effect on environmental preservation.

Much of Patagonia’s environmental credibility comes from this involvement with grassroots organizations, and in particular the cash donations, as they prove that the company was willing to put its money where its mouth was.

More important than the dollars donated, more important than the legal battles with the Trump administration, what in my opinion is by far the greatest contribution of Patagonia is its impact on our culture.

Patagonia has created an army of millions of environmentalists. When the company has been early adopters of innovative, environmentally friendly techniques and approaches (such as around product lifecycle), it has been incredibly smart and effective in its communication to consumers.

By creating a sense of shared identity, a “cool factor” (#fellowkids) and sensitizing parka buyers to technocratic topics such as supply chain transparency, Patagonia has transformed the conversation around environmentalism and made it a defining part of many people’s identity. That shift is incredibly hard to quantify and to value in dollars and cents — but in my mind, it is of much greater import than any specific tangible initiative Patagonia conducted (although also the result of those initiatives).

Why wouldn’t Patagonia get funded today?

Patagonia as a start-up would not receive funding from “impact” investors today. That’s not to say it couldn’t receive funding from venture capitalists or wealthy individuals (we’ll get to that), but the large pool of institutional investors with a mandate to grow profits as well as impact would turn their noses.

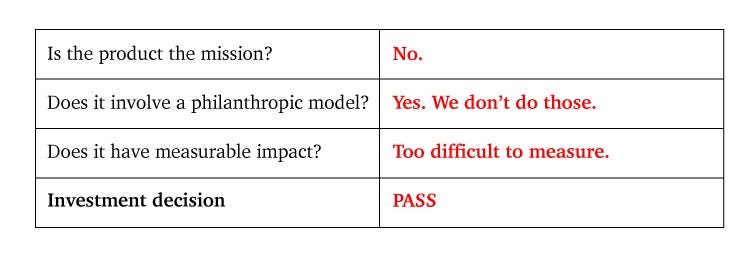

There are three reasons for this.

1. “The product is not the mission.”

This is a mantra you hear a lot in the impact investing world. What it means is that those investors would rather invest where each product sold to directly address the area of impact. For a consumer product, it typically means that the customers are the beneficiaries.

For example, selling an affordable water filter to communities with no drinkable water source: The customers are the direct beneficiaries of the impact.

Patagonia does not fit this definition. Its customers are mostly affluent Americans, not people for whom a jacket makes a life-changing difference. And despite all efforts and initiatives to reduce the company’s footprint, ultimately each additional product sold still has a marginal negative footprint on the planet.

2. “We don’t do philanthropic models.”

As I mentioned earlier, a big chunk of Patagonia’s impact — and the main driver of its credibility and ability to be lead activists — is through the vast sums it donates to environmental charities across the country.

There is currently a backlash in the impact investment community against consumer companies that donate large sums to charities, often pegged to products sold, total revenue or profits.

Adherents to this view have two main arguments for this:

- Argument 1 : Abuse of this model by some companies.

Long story short, 1-for-1s and other philanthropic models have been easy targets of “greenwashing” — using marketing to promote the perception that an organization’s products, aims or policies are environmentally or socially friendly.

- Argument 2: Building purpose at the core.

A corollary to the “product being the mission” philosophy is that you then don’t need to donate to charity because your business is already creating its own impact.

Both of these arguments have some basis to them, but are ultimately dangerously over-simplistic. The fact remains that they are the “conventional wisdom,” and so … sorry, hypothetical new Patagonia: 89 million, schmillion.

3. “Political and cultural impact can’t be quantified.”

Impact investors are all about finding ways to quantify the impact of their investments. On principle, you can’t argue with that. If you can’t quantify the impact of your impact investments, how can you prove that you’re not just a 100 percent financially driven investor?

But in the case of Patagonia, the largest share of its impact is cultural, and to some degree, political. There is no way to A/B test how different the cultural landscape would have been and what different micro-decisions millions of consumers, business leaders and politicians would have taken if Patagonia never had entered their lives.

That creates an issue that I will attempt to explain with the analogy of a forest. Imagine you are a philanthropist who has backed two reforestation programs. Twenty years later, you want to invest further into the program that has planted the most trees.

Program 1 has accurate tree planting data — they have planted 121 trees. They have myriad sub-metrics and Key Performance Indicators, which I’ll spare you. Program 2 just has this photo of what they’ve planted:

We don’t have a clue about the exact number of trees planted by Program 2, but intuitively we can say that it’s an order of magnitude greater than the 121 trees of Program 1.

This isn’t a perfect analogy, because in this case you might be tempted to think that Program 2 doesn’t have its stuff together because it has no reporting in place. But you do know that your initial investment in Program 2 got a lot more impact than Program 1 — you just don’t know if it’s 100x, 1,000x or 1 million x.

This is a cognitive bias that I saw a lot during my previous life as a data analyst, especially among MBA-trained middle managers, who self-describe as “data-driven.” It is more comforting to work on something measurable — no matter how insignificant — than to take a risk on something large and unquantifiable, even if it is to provide a better outcome by orders of magnitude.

Patagonia scorecard summary

OK, so that pitch didn’t go well. But if it had, would baby Patagonia become the force it has become, the source of all our love and admiration as it stands today?

Independent ownership is key

Patagonia, Dr. Bronner’s and many other companies leading the regenerative organic movement have one thing in common: They are independently owned.

Patagonia is almost entirely owned by its founder, and Dr. Bronner’s is still owned and operated by the Bronner family, three generations in. What they have in common is that they define long-term as multi-generational (vs. five to 10 years for Wall Street), and that they have the freedom to make decisions that go against conventional business wisdom. Critically, this means they are less likely to suffer from the cognitive bias described earlier. Even more critically, it means they can take into account people and planet — not just to drive business results, but as an end in itself.

This behavior and ethos, sustained over decades of business, is hard to find outside of entrepreneur-owned or family-owned business. I wish I could name one, but I cannot.

A lot of the messaging I see from “impact investors” is hard to distinguish from regular old private equity language. “Long-term” generally means five to seven years, and there is an intense focus on “exit.” I don’t believe you can create a new Patagonia with that kind of mindset.

If your goal is to offload your company to someone else in five years, you will make decisions that maximize value creation on that timeframe — not 10 years, certainly not 50 years. And that short-term pressure inevitably leads to shorter-term decisions around people and planet.

Institutional investors currently don’t typically think past their own timeline, which as I pointed out is still short. The goal is to exit and cash out on a return after a few years. Once the company is out of the portfolio, it’s someone else’s problem, and you move on. That approach is problematic, because it means the turning point isn’t when the company exits, it’s when that institutional investor joins in the first place. That is when the direction of the company is defined.

So how do we pool this immense reserve of money, energy and goodwill — that brought people to even consider investing for impact — to break out of this cycle and create the real Patagonias of tomorrow?

What would it take to fund the next Patagonia?

First off, it’s important to acknowledge that the world has changed a lot since Patagonia started in 1973. We’ve gone from a time where the concept of a computer was science-fiction to our current day, where always-on commerce is disintermediating your data to give you real-time recommendations and scalably target other individuals who resemble you.

Feel free to circle back and leverage this laser-focused database in the future.

As the steward of the company’s mission and vision, across customers, employees, shareholders, community and environment, the entrepreneur needs to partner with backers who 100 percent share their vision. They need to operate with a shared understanding of purpose, governance, vision, timeline and values. Finding that fit is no easy task.

Here is a collection of ideas floating around that I think deserve some attention.

New modes of financing

There is a false truism out there that there are “standard” term sheets for investment. Venture capitalists successfully have convinced lawyers and other participants in the investment process to push a model of financing that drives outcomes where shareholder gains are the only objective of the company, and that that’s specifically through an “exit.”

By holding pure equity (ownership) in the company, the only way this type of investor can achieve a return is either when the company is sold to a buyer or listed on the public markets (IPO).

Yet the idea that this type of investment needs to be the norm is bull.

There have been countless instances of creative term sheets that create healthy incentives for companies to prosper and create positive impact — and critically, don’t make a company sprint toward the exit. There is a movement quietly growing to spread these ideas, and make more entrepreneurs aware that there is even a choice.

Luni Libes has promoted a revenue-based equity model, and a collaborative effort between entrepreneur John Berger, Boma and ADAP has come up with a thoughtful similar concept called Performance Aligned Preferred Stock. Both attempt to align impact investor and entrepreneur incentives and allow businesses to operate in a healthier way.

Neither is a panacea — each business is different and needs to think uniquely about how to align its investors’ incentives with its own. But these alternative solutions deserve much more airtime and adoption. If one major institutional investor were to announce it was adopting a similar investment model, I have no doubt a wave of change would ripple through that community.

This in turn would create a massive system change as a whole generation of impact-oriented companies would be set up to prosper, and potentially grow into future Patagonias.

More early-stage impact investment

A closely related issue is the microscopic volume of institutional impact investment directed toward early-stage social businesses (less than $1 million–$2 million in revenue). Startups in this phase looking for funding do not have access to debt capital either. The main players filling the gap are venture capitalists and “angel investors” — the majority of which view the world through a venture capital lens, in my experience — especially as the media has sensationalized that type of investing.

We need more leaders in the impact investment space to fill this void, set new norms for financing these early-stage enterprises and create an alternative to venture capital for those profitable businesses that could become immensely impactful.

In particular, we need more infrastructure and networks for early-stage impact investment such as Social Venture Circle. They serve a critical function in bringing together those independent investors with purpose-driven entrepreneurs.

There is a big opportunity for university endowments to play a role in this space, especially if the schools have strong social entrepreneurship programs or MBA degrees with a sustainability or social impact angle.

More lenders such as Accion (a nonprofit) are willing to lend something to very new socially minded companies.

Change the culture

In today’s gilded age, in a period of great societal and economic transformation, we need consumer-facing companies with strong values that will drive this transition era toward an outcome that is regenerative.

The Certified B Corporation movement is tackling many major, complex issues, whether it’s diversity and inclusion, environmental remediation or worker empowerment. Fixing the incentives, culture and system around financing would have a massive impact across all of them. As a business leader, overhauling our economic system may sound overly ambitious and unrealistic.

But what we’re talking about here are small changes that a small number of people have the capacity to make. They amount to a quiet, radical realignment of our economy. That is healthily ambitious and definitely not unrealistic.

There is so much energy out there: I am inspired by many people I have had the opportunity to meet in the field of social and environmental impact. So many people are devising new solutions, and many others have the appetite and money to make them a reality.

We have a whole new generation of entrepreneurs who are both idealistic and business-savvy. The opportunity never has been greater to make a decisive change in how the engine of business operates in the country and globally, and to give birth to many little Patagonias.

This article was originally published on B the Change, for which it was abridged. You can view the original, more in-depth piece here.