How the maker of Jack Daniel’s is fighting to save white oak forests

Oaks serve as habitat, food, and shelter for innumerable other species. They're also used to age bourbon. Read More

Without oak trees, there is no bourbon. Legally, bourbon must be aged in charred new oak barrels in the United States. And one species, white oak, creates the strong, smooth taste and rich color we’ve come to expect.

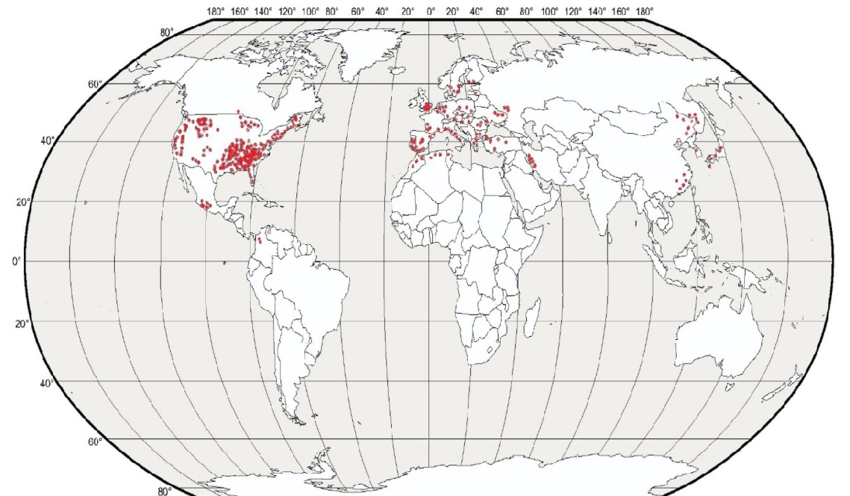

Unfortunately, oak trees are declining globally. Oak decline has been recorded in 39 countries and 31% of the 430 known oak species are threatened with extinction. Mature oaks are dying at higher rates than expected due to a combination of environmental stressors. At the same time, there aren’t enough young oaks to replace them (i.e., regeneration failure). Even when there are enough young oaks, they often fail to reach maturity (i.e., recruitment failure).

The sourcing of whiskey barrels is inseparable from the long-term health of North American forests. Oaks are keystone species, serving as habitat, food and shelter for innumerable other species.

This phenomenon has been well-documented in scientific literature for decades but has largely gone unnoticed by policymakers and the general public. The bourbon industry, though, is well aware of this potentially existential threat.

Brown-Forman, parent company to Jack Daniel’s, recognized the long-term risks associated with oak decline as far back as 1998. Over the past few years, the company has taken a more public-facing approach by developing Dendrifund, a non-profit seed fund, and advocating for federal policies to improve the management of oak forests.

“No one cares about regeneration until you tell them it will impact their bourbon”, said Dendrifund Executive Director Barbara Hurt.

Map of the distribution of oak decline worldwide

Source: “A review on oak decline: The global situation, causative factors, and new research approaches.” Forest Systems, 2023

Dendrifund’s goals go beyond tree-planting

Dendrifund began as a traditional grantmaking organization. In her first few years at the organization, Hurt was charged with figuring out “how to make a bigger difference,” she told me.

Recognizing that region-wide conservation requires collective action, Dendrifund, which is funded by the Brown-Forman Foundation and a portion of the proceeds from the company’s sale of the Finlandia vodka brand, partnered with the American Forest Foundation and the University of Kentucky to launch the White Oak Initiative.

After completing a 4-year conservation assessment and planning process that involved multi-state collaborations with other industries, trade associations, private landowners, scientists and government agencies, the White Oak Initiative came up with a set of goals and a plan to achieve them.

The collective goal is to regenerate 100 million acres of white oak forest by 2070. Stakeholders have identified 10 recommended forest management practices to reach this goal. They include:

- Reducing competition through forest management techniques such as crop tree release and the harvest of non-oak species in densely wooded young forests;

- Establishing environmental conditions that expedite oak growth and regeneration through prescribed fires and other methods;

- Assisting acorn germination through practices that include scarification (i.e., partial removal of the seed coating) and herbivore exclusion (e.g., managing the abundance of animals that consume acorns).

Private sector advocacy can catalyze conservation policy

Brown-Forman can’t implement changes to forest management because it is not a landowner. Its most powerful tool is “leveraging their brands to bring people to the table,” said Hurt.

The vital role of the bourbon industry in Kentucky’s economy has brought Republicans and Democrats together for a common cause. Representatives Andy Barr and Morgan McGarvey have introduced the White Oak Resilience Act, a bipartisan bill backed by Brown-Forman.

In its current state, the bill includes:

- Initiating oak restoration pilot projects in national forests;

- Assessing the presence of oaks and potential for restoration on all lands held by the Department of the Interior;

- Developing and implementing a national strategy to increase federal, state, Native American and tree nursery capacity to address the nationwide shortage of tree seedlings;

- Establishing government-university partnerships to address key research gaps; and

- Establishing a White Oak Restoration Fund.

If passed, the White Oak Resilience bill could dramatically catalyze efforts to address oak declines. At the same time, measuring the success of those efforts will be critical.

Success can be hard to define but that’s a bad excuse for inaction

Like many companies, Brown-Forman does not have official biodiversity commitments. The challenge of efforts like the white oak restoration campaign is distinguishing between projects that will have negative, neutral, or positive impacts on species’ survival.

In a recent meeting of the Trellis Network Nature and Carbon communities, members expressed the difficulty of defining what a “good” nature-based project looks like. Something that appears to be effective today might not generate positive outcomes for nature, including people, in the long term.

Improving oak forests is an expensive, time-consuming multi-generational process that requires complex relationship-building. And negative public perception of forest management techniques such as controlled burns, select harvesting or pruning of trees and hunting may cause reputational risks.

“But we do know that we will get closer to good, or maybe even great, for future generations if we get as many diverse people and perspectives to work together to envision that future”, said Hurt. For Dendrifund, “success includes value chains that are more connected through relationships, knowledge sharing, and deeper understanding beyond transactions.”

Many US-based companies I speak with on a regular basis have expressed hesitation to announce specific biodiversity commitments because of potential backlash around the failure to meet carbon goals and a hesitance to act with partial or imperfect data. The campaign to help oak forests thrive again shows the power of corporate advocacy to amplify an issue that’s well-documented in the conservation world but typically ignored more widely.