Why the US needs to get on track with high-speed rail

The possibilities for high-speed rail innovation are many, and once the lasting infrastructure is built, the benefits to communities are long-lasting. Read More

In the $1 trillion infrastructure bill passed by the U.S. Senate, just $66 billion was proposed for rail infrastructure over eight years and $39 billion for public transit over eight years.

To get a sense of these numbers, Alphabet’s revenue in a single year, 2020, was over $180 billion. The American Society of Civil Engineers rates U.S. transit infrastructure at D-minus, with the backlog for transit projects at $176 billion and the backlog for passenger rail at $45 billion. This public investment is vital for maintaining and upgrading the existing rail infrastructure, yet the allocations still fall short for building out a competitive high-speed rail network.

Even as corporate net-zero pledges and climate funds abound, there seems to be little attention paid to investing in electric rail. Shipping is having its moment with bankers pledging to help decarbonize the sector. Electric cars and trucks are viewed with increasing optimism by major automakers. Even aviation — one of the most difficult modes of transport to decarbonize — has seen breakthroughs in electrification and zero emissions efforts.

What about rail? As a soft indicator, since 2018, there has been literally one article per year on rail on GreenBiz.

High-speed rail lines, which can be used for both passenger travel and freight service, are generally characterized by speeds of at least 200 miles per hour — providing convenience, safety, lower environmental impact and higher community benefits when compared to driving. At these speeds, high-speed rail services exist in over 20 countries.

The United States has zero. The fastest rail system in the U.S. is the Amtrak Acela Express along the Northeast Corridor (NEC), with speeds of up to 150 miles per hour but with averages around 66 mph. Even though not yet high-speed, Amtrak claims that traveling by the Amtrak NEC train produces 83 percent less carbon emissions than driving alone and up to 73 percent less than flying. Since 2021, the rail company has provided trip-specific carbon emissions savings to NEC customers.

Japan is home to the first high-speed system, known as Shinkansen, or “bullet train,” which began in 1964. France was the next economy in line — by 1981, France’s first high-speed rail line was created between Paris and Lyon. And China is home to the world’s largest high-speed rail network.

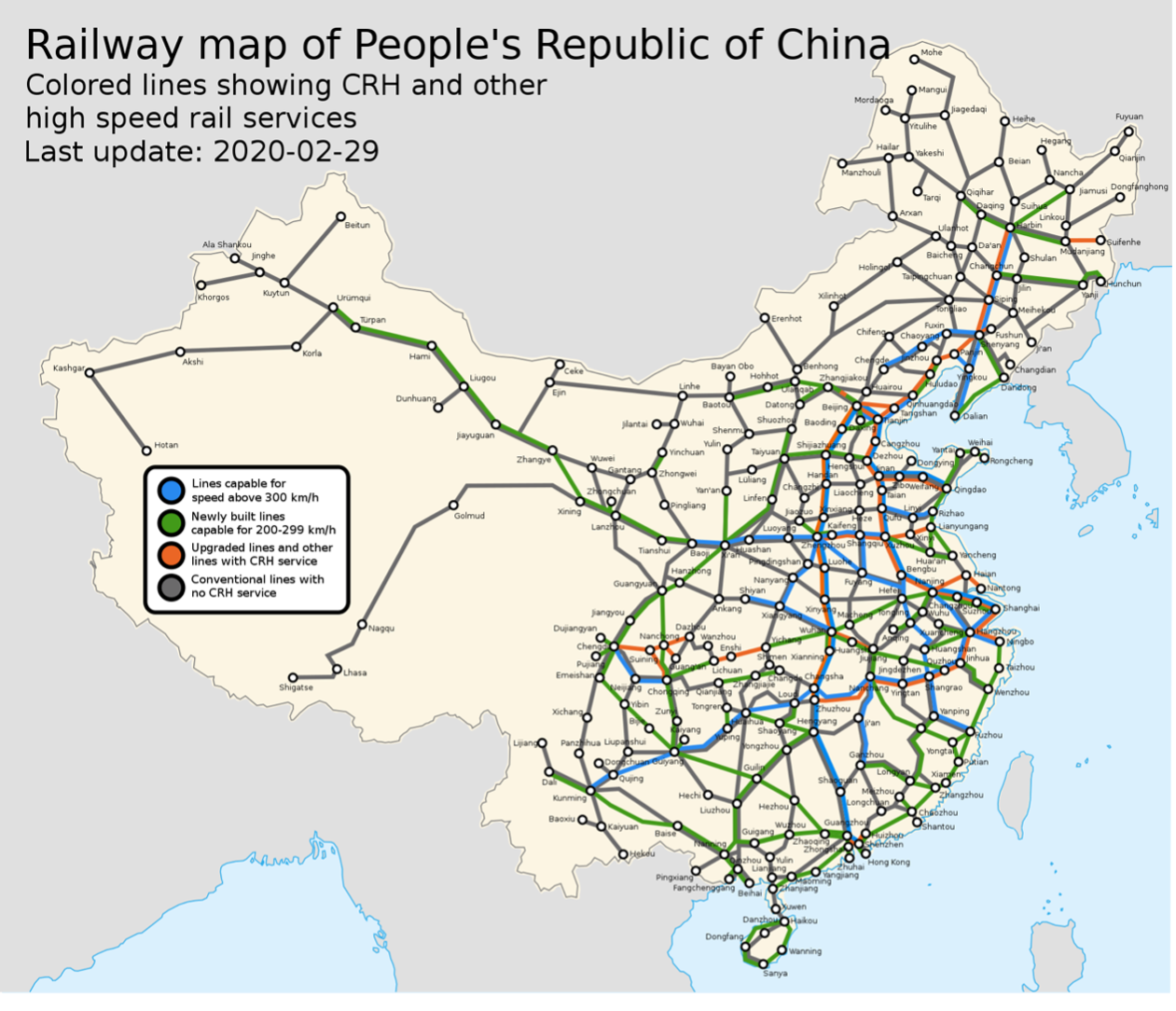

After the Chinese Ministry of Railway announced plans in 2006, more than 23,500 miles of high-speed rail traverse a country roughly the same geographical size of the U.S. While China’s large population contributes to the profitability of high-speed rail (the Beijing-Shanghai line made a net profit of $29,000 in 2019), most Chinese cities with as little as 500,000 people have a high-speed rail link. In 2018 alone, China spent about $117 billion on railway projects.

The above figure is a map of the high-speed rail system in China. Source: Wikimedia

The barriers to high-speed rail (and rail at lower speeds) are numerous in the U.S. The obstacles include local NIMBY-ism, construction cost overruns of previous rail plans and laws that disadvantage the majority public interest and place small municipalities at the center of power of what are state or multi-state level infrastructure decisions.

Amtrak, also known as the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, is the national rail operator that operates more than 300 daily trains in the U.S. and Canada. However, Amtrak operates most of its network, around 70 percent, on tracks owned by other railroads. China’s high-speed rail success was built on getting many things right that the U.S. has historically gotten wrong — including large public investment, exercising powerful right-of-way laws, rapid build-out, forecasted travel demand planning and low fares.

The benefits of high-speed rail are plentiful and difficult to fully quantify. Historically, benefits have included shortened travel times and thus higher productivity, improved safety and facilitation of labor mobility, as well as increased economic activity associated with tourism, construction and other productive uses near new stations. High-speed rail networks also reduce operating costs, accidents, highway congestion and greenhouse gas emissions as some air and auto travelers switch to rail.

As poverty rises in U.S. suburbs, high-speed rail could provide a means, especially when connected with local light rail systems, to access jobs and wealth. Studies indicate that high-speed rail connections have important spillover effects in supporting an extensive supply chain and manufacturing industry, which creates new companies. In addition, HSR helps reduce the negative impacts that extensive car use entails. According to engineer and historian Henry Petroski in “The Road Taken: The History and Future of America’s Infrastructure,” the delays caused by traffic congestion alone cost the U.S. economy over $120 billion per year.

In the era of COVID-19 and the corresponding re-working of many workplaces, high-speed rail provides an additional benefit: worker flexibility. With many companies deciding that a full remote working or twice-a-week in-the-office policy is not only feasible but better for a number of well-being and productivity outcomes, high-speed rail could offer more choice and options for workers, and more access to talent for employers. Imagine employers in California that can have equal access to Oakland and Los Angeles employees; likewise for Dallas-Austin-Houston; Atlanta-Nashville-Birmingham; Chicago-Detroit.

Transportation represents the largest source of climate-harming greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., and the climate benefits of high-speed rail are clear. According to Project Drawdown, high-speed rail reduces carbon emissions up to 90 percent compared to driving, flying or riding conventional rail, and is the fastest way to travel between two points that are a few hundred miles apart. High-speed rail also helps build in resiliency and needed redundancy to face the impacts of climate change, such as when planes are grounded due to severe weather.

There are future plans to build high-speed rail in the U.S., and they have been plans for a long time. Without adequate public investment, better accounting of benefits and changes to the laws that impede progress, they will remain just plans, depriving the economy of the low-carbon infrastructure that’s needed to connect communities, create jobs and mitigate climate change.

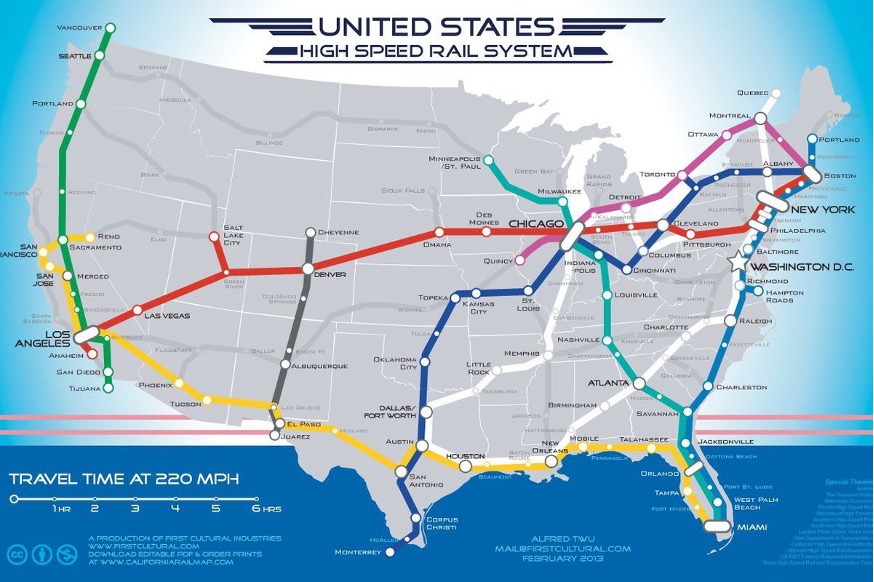

The high-speed rail wish list includes the following lines: Denver to Albuquerque, New Mexico; Las Vegas to Los Angeles, Dallas to Houston, Nashville to Atlanta, and almost everything to Chicago. The wish list map went viral in 2020, garnering massive support especially among younger generations of climate-conscious and community centered Americans. This (French) TikTok video, with over 35,000 views, illustrates how the lack of high-speed rail in the U.S. is an embarrassment. The New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens (NUMTOT) Facebook group has over 220,000 members.

The figure above represents a U.S. high speed wish list. Source: Vox

In reality, high-speed rail may be more of a piecemeal project in the U.S. “We are more likely to start with incremental improvements, for example along the Northeast Corridor, as a path towards high-speed rail in the U.S.,” explained Darnell Grisby, executive director of TransForm. The next low-hanging fruit is within the country’s largest sub-national economy: California. Some of the fastest growth is projected to occur in the Central Valley, where a true high-speed line is under construction connecting Merced to Bakersfield. Once complete, it may serve as inspiration to complete other high-speed rail projects.

As time passes and construction costs increase, the political support for new rail projects tends to decrease. That decline in support is often overly focused on the metric of “cost per rider.” But the economic benefits of rail, including high-speed rail, are far-reaching and cumulative. “In the first years after BART opened in 1972, ridership was relatively low and there was little development around many stations. Over time, BART has become an economic backbone for the region and ridership has more than tripled since then,” noted Stuart Cohen, a transportation consultant and co-founder of TransForm, referring to the Bay Area Rapid Transit system, which connects the San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland areas.

There are many ways to reduce the costs of building high-speed rail, one of which is standardizing designs and procedures, which greatly helped the Chinese high-speed rail network. The construction cost of the Chinese high-speed rail network, at an average of $17 million to $21 million per kilometer, is about two-thirds of the cost in other countries.

However, beyond cost reduction, there is a need for a paradigm shift in thinking about the cost benefit analysis of high-speed rail.

In a report prepared for the American Public Transportation Association (APTA), the notion of a private franchise was juxtaposed with that of a public franchise, and it is with this public lens that most high-speed rail projects are built globally. The authors describe a public franchise as “a business venture that has parallels to a private franchise, except that its goals are to fulfill public rather than private interests.” They go on to detail examples of what should be included in the calculation, within six categories: user benefits; societal spillovers; spatial connectivity; risk reduction; local land impact; and operator impact.

Today, most European Union countries finance the majority of infrastructure using national-level public investment whereas the U.S. only finances 25 percent of public infrastructure with federal public dollars, driving local municipalities to bear most costs. In addition, as the U.S. lacks a high-speed rail industry, the development of one could create “Made in the USA” supply chains that support local manufacturing and engineering. The early railway system serves as precedent: It expanded industrialization and lowered the cost of transporting goods across the country. One could argue that the low speed rail helped turn the once-isolated California into an economic powerhouse.

The possibilities for high-speed rail innovation are many, and once the lasting infrastructure is built, the benefits to communities are long-lasting. The startup Midnight Trains is launching luxury sleeper trains in Europe, including France, Germany and Denmark, from 2024. Perhaps the sustainability departments and climate units of corporations should add the public franchise of high-speed rail to their climate lobbying efforts. After all, they, too, would benefit from a serious U.S. endeavor in zero-emissions transportation that is safer with added community benefits compared to cars. High-speed rail should be a carve-out within any infrastructure and budget reconciliation package.